Non-performance anxiety

How dangerous are non-performing bank loans for Bangladesh’s economy?

So many bank scams and scandals have rocked Bangladesh in the past decade, many of them linked to criminal or unpaid loans, with the most recent being Janata Bank’s rescheduling of over Taka 1700 crore ($200 million) of loans made to AnonTex Group, a company which is alleged to have published false tender notices and laundered money abroad.

But how serious is the problem of non-performing loans and what are its macroeconomic consequences?

Six months ago, in September 2019, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published an “Article IV” report on Bangladesh’s economy after holding extensive discussions with government officials. This report stated that the “failure to effectively address the problems in the banking system, including high non-performing loans” posed a “medium” likelihood risk to the economy, and its “expected impact” would be “medium-to-high”. It added, “High and increasing non-performing loans and low capital adequacy would hamper the banking sector’s ability to finance business investment, add fiscal burden, and hamper growth.”

Let’s unpack this. In doing so, we are going to look at official data. Whilst there is considerable scepticism about the veracity of official figures, there is nothing else to go on. And as it happens, even official data tell a potentially scary story.

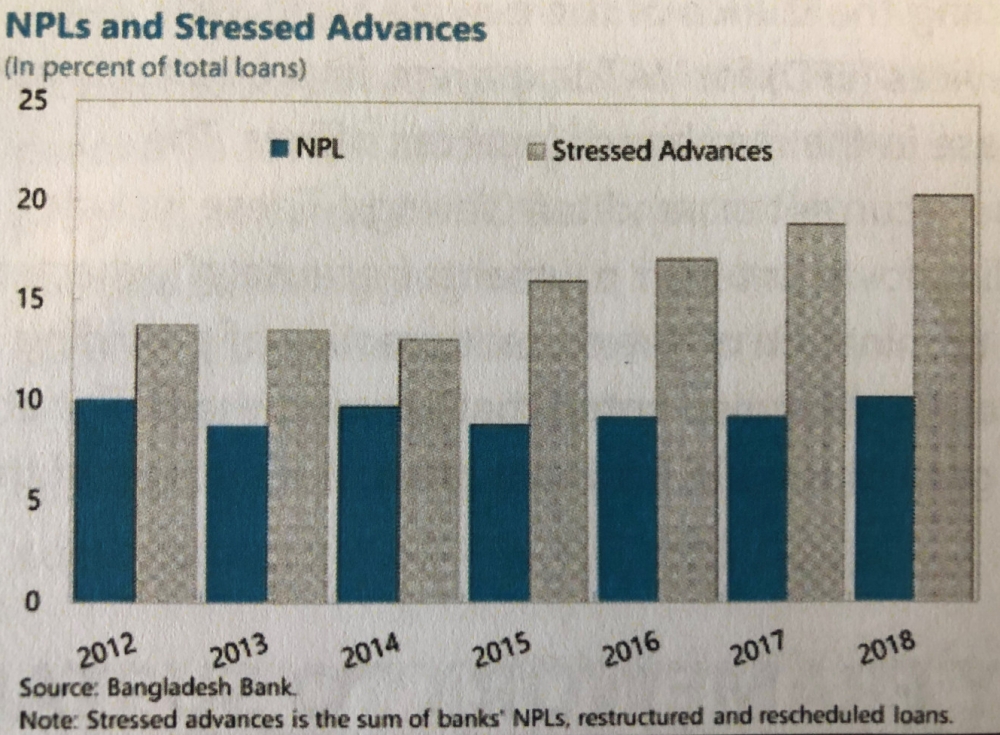

Non-performing loans (NPL) are those loans where the borrower has failed to make interest or principal payments for an extended period of time, typically 90 days. Obviously, the higher these loans are relative to the total amount of loan a bank (or the banking system collectively) has made, the worse things are. One of the charts from the Article IV report shows that about 10% of total loans made by Bangladeshi banks are not performing.

It should be noted that the IMF thinks that these figures are probably too low. As its report states, “The published NPL ratio likely underestimates potential problems in the banking sector. There has been a growing trend of loan rescheduling and restructuring.”

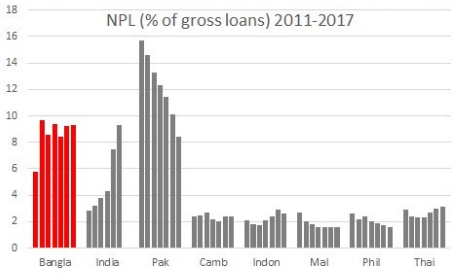

However, let’s stick to the official figures. The first question to ask is, is 10% NPL high? One way to answer that is to look at the ratio in other similar countries. Another chart, based on research by Junkyu Lee and Peter Rosenkranz of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), shows that it is much higher than Southeast Asian countries, though maybe not so compared with India (where it has been rising fast) and Pakistan (where things appear to be improving).

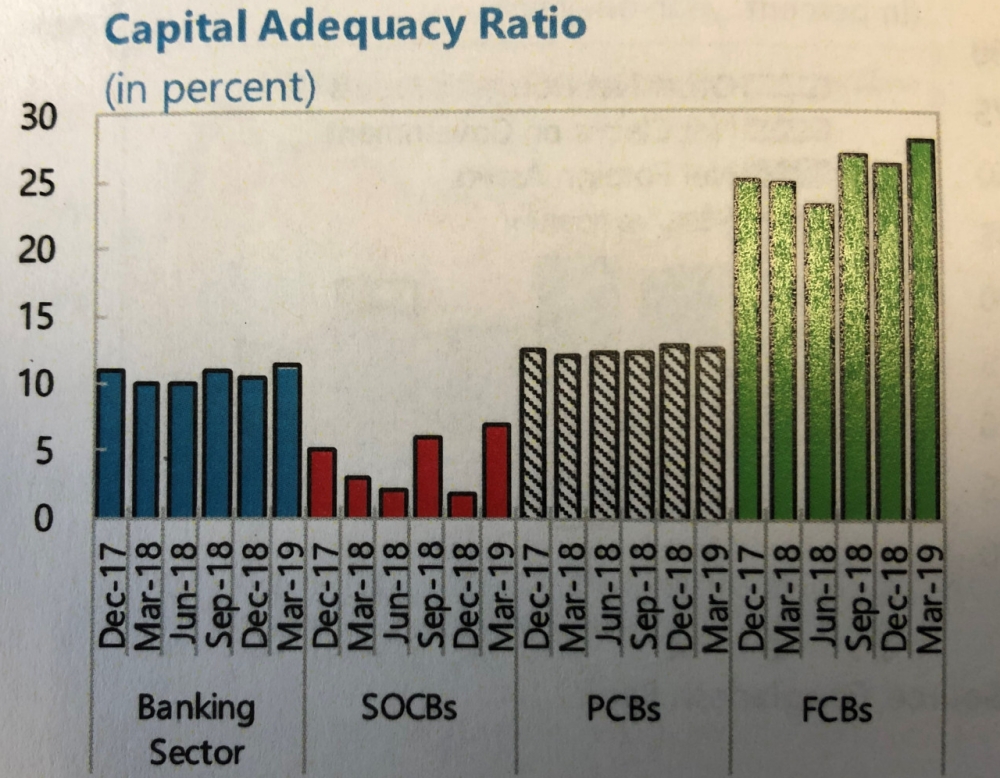

Things are, however, more complicated than the headline ratio suggests. Firstly, the problem appears to be far worse in the state-owned commercial banks (SOCB) — Sonali, Janata, Pubali and Agrani — where 30% of loans were not performing at the end of 2018. A related problem is that these state banks are dangerously undercapitalised — that is, they do not have enough capital to cover their risks. This is shown by another chart — from the IMF report — of “capital adequacy ratio”, which is a measure of how well placed a bank is to cover its risk. According to the internationally accepted Basel III convention, this ratio should be at least 8%. In the table, FCBs are Foreign Commercial Banks and PCBs are Private Commercial Banks.

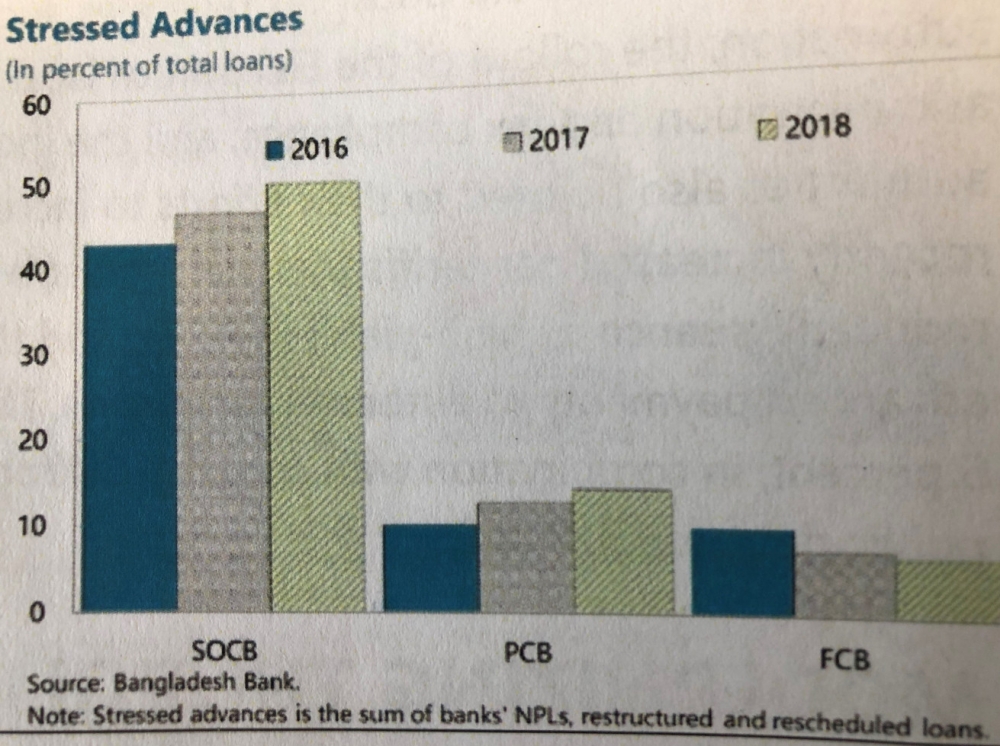

More importantly, the problem is potentially worse because rescheduling and restructuring are dramatically on the rise. Stressed assets — that is, the sum of non-performing as well as restructured and rescheduled loans — went from less than 15% of total loans in 2014 to over 20% in 2018. Further, the rescheduling and restructuring are happening not just in the state owned banks, but also private commercial banks. This can be seen in the next chart, again from the IMF report, which shows the stress assets as a percentage of total loans of SOCBs and PCBs edging up every year between 2016 and 2018.

The high level of stressed assets limits banks’ ability to provide fresh lending for new projects, dampening economic activity and income. And today’s rescheduled or restructured loans could well be tomorrow’s non-performing loan.

So, what is causing the banks’ troubles? And if the stressed assets did become non-performing, how bad could the hit on the economy be? The ADB economists’ paper can suggest some answers on both counts.

Studying 165 commercial banks in 17 emerging market countries in Asia over two decades, Lee and Rosenkranz find that the most important reason for the rise in non-performing loans are usually macroeconomic — that is, banks find that their borrowers are unable to repay loans when the economy is in a recession or is faced with adverse shocks such as a sudden spike in inflation.

But according to official data, Bangladesh is not in macroeconomic difficulty. To quote the IMF, “Despite solid economic performance, the NPL ratio remains high, particularly for SOCBs, and the amount of restructured and rescheduled loans continues to increase.”

If the answer is not macroeconomic, is it microeconomic? That is, could it be that the banks have been lending to poor borrowers? For example, undercapitalised banks tend to find themselves lending to more risky borrowers in the hope of earning higher yields. The ADB economists do find that the low-capitalised banks tend to have higher NPLs, which is consistent with the Bangladeshi situation.

Digging yet deeper, maybe the state banks were just poorly managed — not a difficult thing to imagine in the context of, say, Janata Bank, is it? This could manifest itself in two ways: to save costs, banks cut their monitoring function or they engage in excess lending. In the Bangladeshi context, this second possibility does not sound far fetched at all.

What might happen if the stressed assets become NPLs?

The ADB economists’ results imply that if the NPL ratio rose from 10% to 20% over three years, GDP growth would slow by about 1% point, all else being equal. That is, even on the basis of official data that may well understate the gravity of the situation, there is a clear problem with the banks.

So, what should be done?

The good news is that there are technocratic solutions to these problems — tightening the criteria for rescheduling or restructuring of loans, strengthening the banks’ corporate governance, enforcing bankruptcy laws and such like. Coupled with selected recapitalisation of banks, these measures can de-risk the banking sector without causing a hit to the economy. This has been done around the world over the years, with technical assistance from the IMF and other international partners.

The bad news is that these technocratic solutions require technocrats — regulators and judiciary — to work independently, transparently, and with credibility. None of which is present in today’s Bangladesh.●

Jyoti Rahman is an applied macroeconomist. An earlier version of this analysis was published on his blog.

🔗 Bangladesh : 2019 Article IV consultation

🔗 Nonperforming loans in Asia: Determinants and macrofinancial linkages