Police troubles: IGP vs. Commissioner

A power struggle at the top of Bangladesh’s police service leads to the transfer of two police officers in opposing camps.

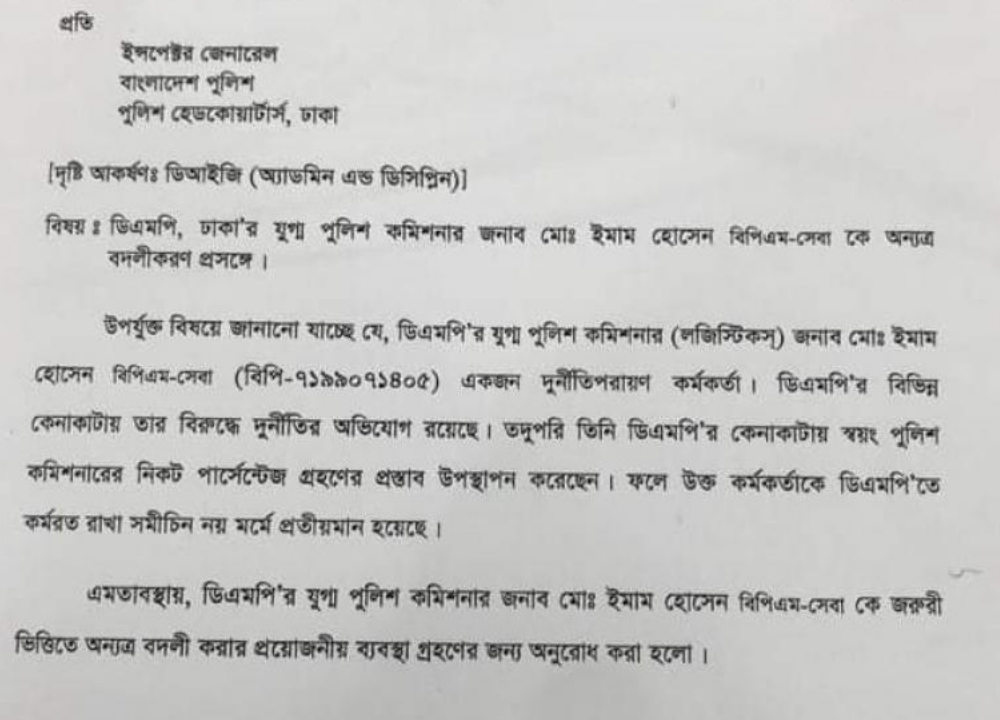

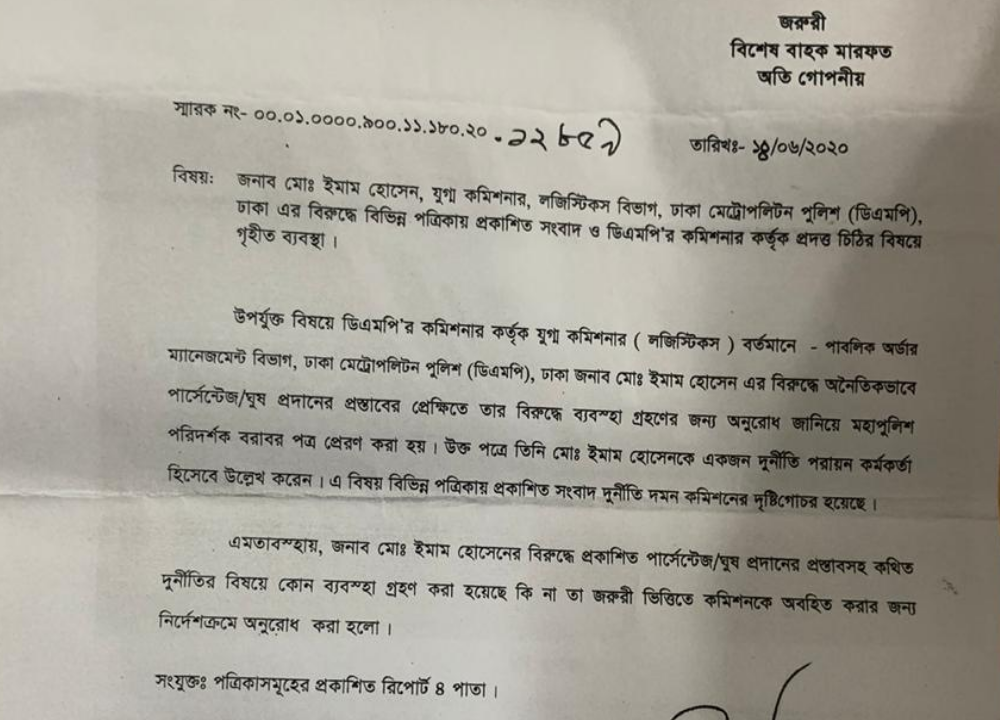

On May 30th 2020, Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP) Commissioner Shafiqul Islam secretly sent a letter to Inspector General of Police (IGP) Benazir Ahmed, accusing a high-ranking officer of committing corruption in procurement and of having offered him a cut — “percentage” — from future bribes.

The letter, which would be leaked to the media, requested the police chief to transfer the accused officer, Imam Hossain, a “superior officer”, from the DMP on an urgent basis. In Bangladesh police, superior officers are recruited through Bangladesh Civil Services (BCS) exams, considered “first class gazetted officers”, and ranked from assistant police superintendent to IGP, as opposed to “subordinate officers” who are generally ranked from constable to inspector.

Although Hossain was answerable to the commissioner, applicable laws allow only the IGP (and the interior ministry) to transfer or terminate superior officers. Nonetheless, it was a rare, if not unprecedented, anti-corruption dispatch within a force prone to bribery and notorious for turning a blind eye to its personnel involved in gross misconduct.

The US State Department’s latest Human Rights Report on Bangladesh speaks of rampant impunity for the members of the security forces accused of committing human rights violations and corruption. Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), an anti-corruption advocacy group, ranked law enforcement agencies as the most corrupt public institution in Bangladesh, in its latest available perception report released in 2018.

When accused of committing serious crimes, lower-tier police officers often get away with slaps on their wrists — transfers are the most common form of punishment — but superior officers enjoy near-total impunity.

Therefore, by merely recommending to transfer a superior officer for alleged misconduct, the letter appeared to promise a modest yet long-overdue deviation from a persistent culture of impunity for these officers. It has only emerged now, however, the letter was little about corruption at all.

However, this is far from the full story. Interviews with numerous people within the police and Awami League, as well as a review of official documentation, suggests that corruption was not a key concern of either the DMP or the IGP — and that the letter was merely part of a bitter power struggle between the commissioner and the police chief himself. In fact, the entire episode serves as a damning indictment of the collapsing chain of command of a force marred by corruption, increased factionalism, and blatant political interference.

In Bangladesh, the IGP wields overall command over the centralised police force, but DMP is by far the largest unit of the police with thousands of members and jurisdiction all over the capital city, the epicentre of power and politics in the nation of 160 million.

The current IGP, Benazir Ahmed, has been an unabashedly Awami League firebrand in the police, known for thinly veiled political speeches against the opponents of the ruling party in the run up to the controversial 2014 election, boycotted by major opposition parties.

His meteoric rise to the top began just after the Awami League returned to power in 2009, when he was brought back into limelight from obscurity. Originally from Gopalganj, the hometown of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the traditional constituency of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, Benazir Ahmed is seen as an extremely powerful officer.

Since 2009, many senior officers have been superseded to make way for him. From the DMP, Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) to finally the police force itself, he has held almost all significant commanding posts a police officer could ever hold.

Benazir Ahmed has been so loyal to Sheikh Hasina that, it was rumoured, she went against the advice of senior party colleagues to appoint him as the police chief. Meanwhile, Shafiqul Islam, an officer older than but junior to Ahmed by a batch, was appointed to head the DMP last year.

Even before they assumed their current posts, Benazir Ahmed and Shafiqul Islam did not always see eye to eye, according to multiple police officials who have worked in Dhaka for years.

The old feud, when combined with new ambitions of these two men, put them on a collision course, so much so that the police chief even lobbied the prime minister to get Shafiqul Islam removed from his post — a widespread rumour confirmed by a political insider. This may well have been the trigger for the actions of the DMP Commissioner which are detailed in this report.

Threatened by the IGP’s hostile manoeuvres, Islam targeted Imam Hossain, a compromised senior officer loyal to the IGP, to stage a pre-emptive strategic move.

In fairness to the commissioner, Hossain has not been an exemplary officer. As the head of the DMP’s logistics department, he had significant sway over the procurement process of the largest police unit of the country. And, few in the DMP dispute the merit of the allegations levied against him. The commissioner insisted in private conversations with allies that he indeed had received a bribe-sharing proposal from Hossain.

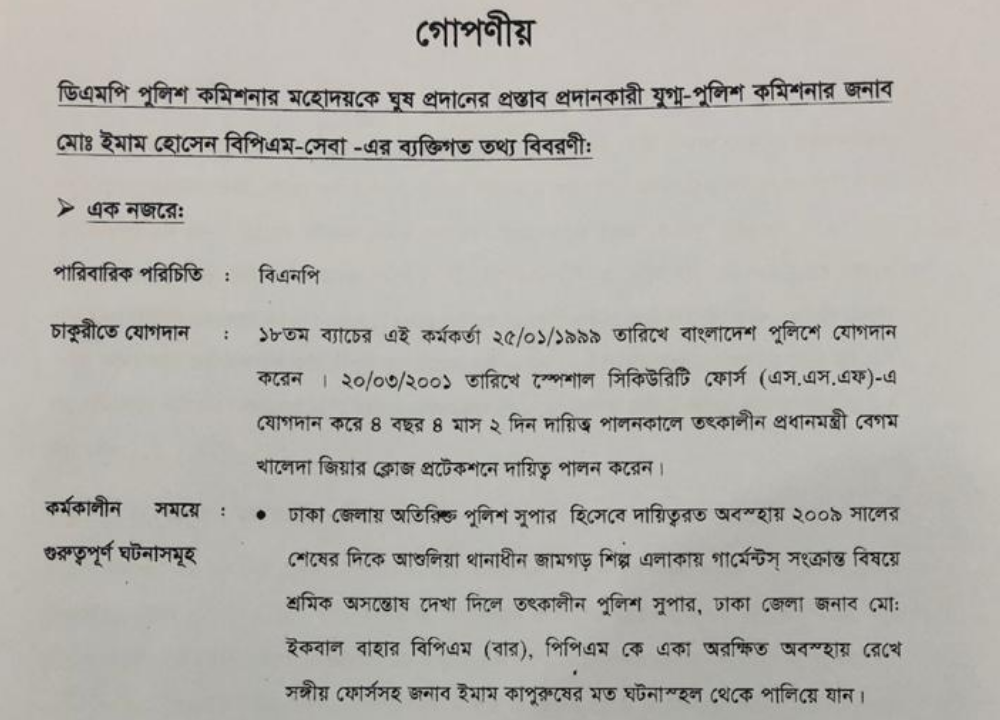

A classified memo prepared by the DMP’s intelligence unit accused Imam Hossain of amassing enormous wealth beyond his legitimate income. For example, according to the document, he owns four houses in Dhaka city and another one in Cox’s Bazar. He has business ties in the United Kingdom and the Philippines and even owns stakes in a commercial FM radio station, according to the dossier. Netra News was not able to independently verify these allegations.

However, we obtained old news reports, which appear to substantiate at least one allegation against him that he set up a charity foundation, Sufia Sundor, for philanthropic works. On behalf of the foundation, Hossain distributed a hefty amount of money, stipend and food over the years, according to the foundation’s own news outlet, bangladesh24online.com.

The confidential report also links Hossain to a murder in a land-grabbing incident in 2014-15. The disputed land in question, it says, was purchased by Hossain’s brother, who then “gifted” it to him. The document notes, however, that no one was implicated in the alleged murder and land-grabbing incident.

The memo, which paints Hossain as a BNP supporter pointing out that he was part of the official security detail of Khaleda Zia when she was the prime minister, also remarks on previous repeated unsuccessful attempts to transfer Imam Hossain out of DMP.

Nonetheless, when he sent the letter recommending Hossain to be transferred, Shafiqul Islam was unlikely to have been driven by his contempt for corruption. After all, if the commissioner really wanted to neutralise Hossain, he could have shifted him from the logistics department to a less significant department within the DMP (which he eventually did). Instead, he decided to throw the ball into the IGP’s court.

By asking the IGP to take actions against Imam Hossain, the DMP commissioner “killed two birds with one stone,” said a police official. “Firstly, if [the IGP] had any plans to remove the commissioner at all, he was forced to back down. Otherwise, it would be interpreted as the commissioner paying the price for speaking up against corruption. Secondly, the striking nature of the allegation meant the commissioner was also able to get rid of an adverse officer.”

Shortly after the letter was sent, it was leaked to the media which angered the IGP more than the letter itself, said a second officer, “He did not like that he was forced to let go of a supporter from an important position of power in the enemy camp.”

Both officials say it was due to the pressure from the police headquarters that the DMP launched an investigation into the leak of the letter and summoned nearly a dozen journalists for questioning, although the probe was later stalled due to pressure from journalist groups.

It is a matter of some irony, that it was not Hossain who had to face an investigation panel for his alleged corruption, but journalists who reported on it. It was as if the leak amounted to a more damaging threat to the police’s reputation than the scandal itself.

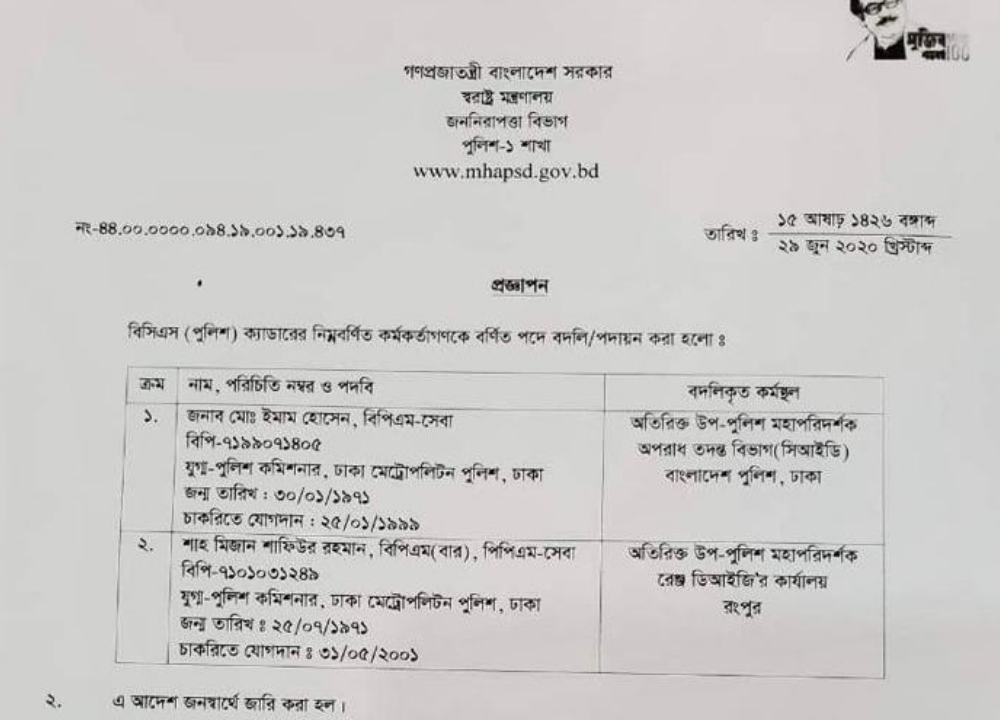

Unable to act against the commissioner directly, the IGP sought to inflict an equally damaging blow to his adversary by transferring Shah Mizan Shafiur Rahman, a joint commissioner (like Imam Hossain) seen as a close ally of the commissioner, all the way to Rangpur, a northern city. A political insider says it was also widely known that the commissioner’s letter about Imam Hossain was Shafiur Rahman’s “brainchild”.

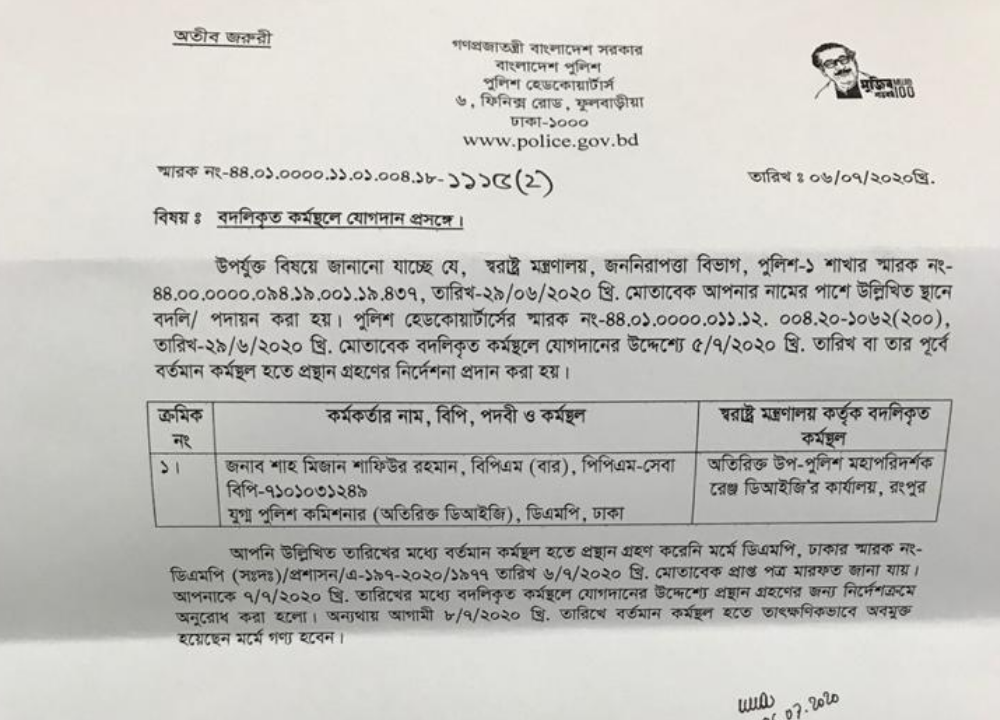

The transfer orders of both Imam Hossain and Shah Mizan Shafiur Rahman came on June 29th 2020, on the same letter from the Public Security Division, Ministry of Home Affairs. Also known as an influential and partisan officer, Shafiur Rahman, initially tried to delay. He lobbied his extensive political contacts, developed during his prestigious tenure as Dhaka’s police superintendent, to override the IGP’s decision, according to the insider. But Benazir Ahmed would not budge.

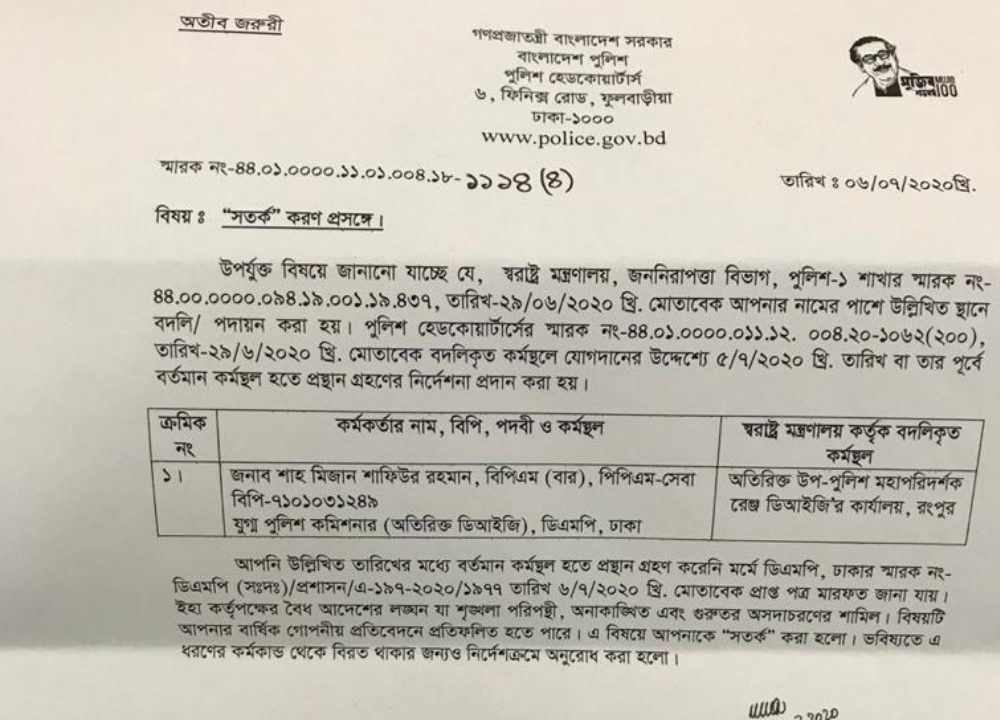

On July 6th 2020, the headquarters sent two letters to Shafiur Rahman. The first one indicated that it had asked the DMP to provide updates as to whether he had obeyed the transfer order. Mentioning that he had failed to leave the station by July 5th, as was asked in the original order from the interior ministry, the first letter asked him to depart for Rangpur by the next day. “Otherwise,” it read, “you will be deemed relieved from the DMP immediately from July 8.”

The second letter, issued on the same day, was harsher. Admonishing him for having committed “a breach of the order of the superior authority, which amounts to serious misconduct,.” The letter threatened to include his failure to abide by an official order in his annual confidential report (ACR). ACR, in the context of Bangladesh’s civil service, is taken into consideration when an officer is assessed for promotion.

It was extremely unusual for the police headquarters to be so vigilantly monitoring whether a mid-level officer complied with a transfer order, let alone reprimanding him for failure to do so. “Such promptness in matters like this is unheard of,” the second police official said. “Clearly, the chief made it his personal mission to teach the commissioner a lesson by removing one of his closest allies.”

Finally, Shafiur Rahman relented and on July 10th, he wrote a post on Facebook saying “anti-government elements” were happy to see him transferred outside Dhaka, adding that he would continue fighting against “corrupt persons” and “misdeeds.”

In the end, he said he was grateful to the “prime minister, home minister, home secretary and IGP and other senior officials.” Bangladesh’s supposedly symbolic but strictly hierarchical warrant of precedence puts the IGP above the secretaries to the government. Perhaps a minor snub?

Imam Hossain, was indeed transferred out of the DMP but instead of being sent to a remote district as happened to Shafiur Rahman, he was sent to the prestigious Criminal Investigation Department (CID) in Dhaka — a small victory for the IGP.

Netra News has contacted the police headquarters seeking comments from Bangladesh Police and concerned officers about the allegations described in the story. We have also sent specific questions to a spokesperson of the police. However, we are yet to receive any response.●