The myth of the freedom fighter and the spirit of 1971

When fighters for freedom turn into traitors to the idea of freedom.

The adage that history is written by the victors is a half-truth. In a system of hegemonic knowledge production, the universally accepted and propagated version of history ends up invariably being written by the West, the only bona fide victor. For Bangladesh, this has meant that the truth of its creation, in defiance of the US empire, has been obscured on the world stage. Nearly five decades on, defining the events of 1971 as the liberation war, not a civil war or an Indo-Pakistani war, is not an established fact. The adverse effects of this shortcoming must not be underestimated — the latter framing has aided convenient, febrile nationalistic narratives on both sides of the India-Pakistan border, while the former label of civil war has been a favourite of Western conservative apologia regarding Pakistan.

There are those amongst the commentariat on the subject of Bangladesh, particularly amongst the country’s elite class and its defenders, who keep foreign hegemony relevant, forever in pursuit of a hawkish Western civilising mission. Sarmila Bose’s book Dead Reckoning exemplified these machinations. Timed to coincide with Bangladesh beginning to gain confidence to tell its own story, it unapologetically committed the heinous crime of historical revisionism and passed it off as the definitive account of 1971 in global discourse.

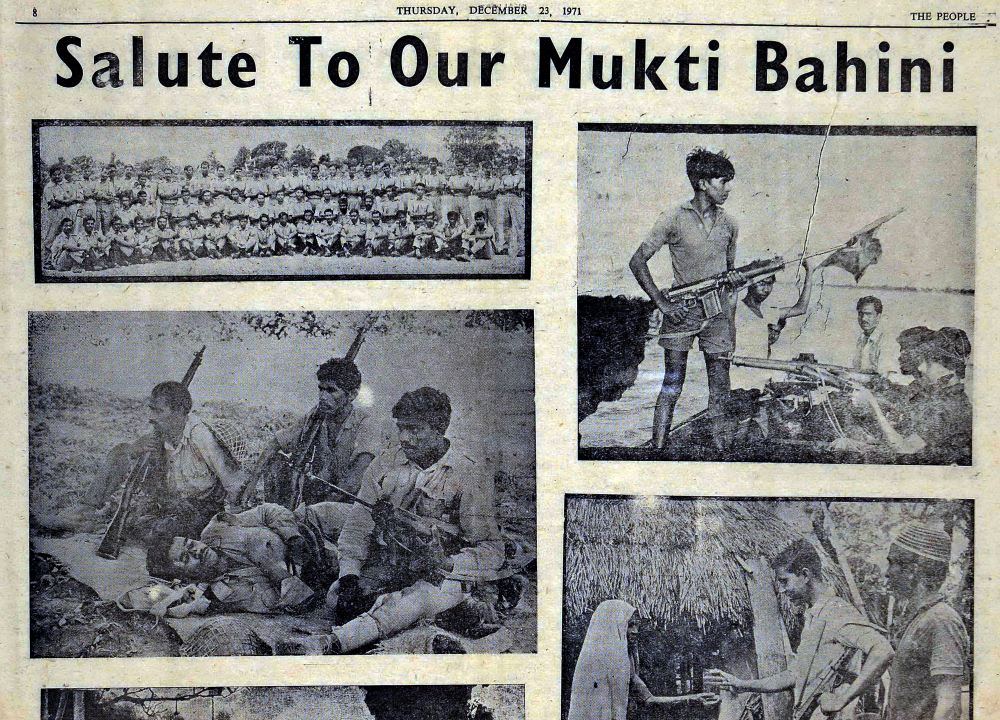

The sensitivity of Bangladeshis on the subject of 1971 is, therefore, understandable. They have been dismissed and derided, their history selectively edited and erased. This is causing new identity crises before the old ones have been resolved as the generations who lived through the war are on the cusp of dying out. Against this backdrop it warrants repeating that Bangladeshis, indeed, oppressed populations all over the world owe a debt of gratitude to the freedom fighters of 1971, those who opposed tyranny and fought for justice and rights with guns, pens, sticks and stones. However, a distinction needs to be drawn between the reality of the freedom fighter and the myth.

Bangladesh has been ruled by political parties and military dictators who have either denied the reality and ignored the myth, or overlooked the reality and relied on the myth. The current autocrats are drawn from the latter category, seizing Bangladesh’s struggle for independence from the people and declaring dominion over it, to construct a lethal national narrative that grants them a divine right to rule the nation.

The myth of the freedom fighter has extricated, precluded and crushed the reality thus. As with the falsehood of the Hajj rituals being an absolute indulgence — on which rests the theological capitalism of Saudi Arabia — that the Muslims of Bangladesh unquestioningly subscribe to, having fought for or claiming to have fought for independence in 1971 absolves Bangladeshis of all sin committed in the years before and since.

Valorising freedom fighters and martyrdom as the epitome of the spirit of 1971 has irredeemably hampered the psychological and intellectual development of an entire nation. It has seen an unhealthy obsession with and desensitisation to violence deeply embedded into the Bangladeshi psyche. Might as a means of expression to win debates has not only been normalised, but has become the norm. In this feral environment of misplaced Social Darwinism’s making, money buys barbarism, barbarism produces power. The deepest pockets are most capable of the worst violence, and, therefore, unchallenged power.

Not content with that alone, the myth of the freedom fighter has ascribed a nobility to men in uniform and the military-industrial complex, in flagrant disregard of both the financial and moral corruption rampant amongst the military ranks. The uniform is unimpeachable, untouchable, its indiscipline and iniquity silenced, its collusion with authoritarians at home and hegemons abroad veiled underneath a forever looming spectre of saviourship.

The myth of the freedom fighter has been constructed by and for the ruling and elite classes. It sets narrow parameters for what being a freedom fighter entails, to establish and reinforce classism under the guise of egalitarianism. The noble promise, proclaimed loudly, is that every individual who opposed Pakistani oppression in the two and a half decades after the British Raj, dreamt of freedom and rights, and acted to realise those dreams, is a freedom fighter. The nefarious practice is that cults of personality are constructed on the purchasable freedom fighter label, spawning fiefdoms once reputations have been laundered. Politicians, captains of industry, lawyers, doctors, engineers, distinguished members of the civil society — the veritable leaders of every conceivable sector in Bangladesh dedicated to preserving the status quo — are the ones who most notably claim the title of or lineage from freedom fighters.

Its benefits are quantifiable and multipliable in a hedonistically capitalist society. There are documented cases of razakars in towns and villages possessing the certificate that is proof of being a freedom fighter, while destitute elderly men and women who verifiably contributed to the country’s independence receive no reward other than being patronisingly paraded twice a year as symbols of purity, resilience and the greatest generation. Elevating the freedom fighter to a qualification readily available in the marketplace of unearned certificates has unforgivably diluted the worth of those meaningful words and devastated the reality of those who deserve to be referred to as such.

A corollary of the myth of the freedom fighter is that, where there are freedom fighters, there must be the dichotomous razakars. While it is true that regional and global hegemons have sympathisers who serve their agendas over the welfare of Bangladesh, unlike authoritarianism, razakar is not an ideology. A razakar fulfilled a specific purpose during a specific time. It is meaningless to refer to anyone under the age of fifty as a razakar, since it reveals nothing about their beliefs. Yet, Bangladeshis of all ages assign this invective to other Bangladeshis of all ages with whom they disagree. It is a false declaration of patriotism, born of nationalism and nativism in service of the ruling and elite classes.

Invoking the spirit of 1971 in this manner is the vogue in twenty-first century Bangladesh, rendering the patriotic duties of dissent, dissidence and seeking justice, rights and the truth anti-state. In the construction of the myth of the freedom fighter, it is forgotten that some real freedom fighters brought the cancer of Islamism and the plague of actual razakars to Bangladesh, rehabilitating and legitimising both in the corridors of power; while other real freedom fighters assisted a rogues’ gallery of autocrats and justified authoritarianism; a few real freedom fighters exploited their kin to accumulate wealth and influence, to expand and escape their gilded cages by encaging free people in squalid, overcrowded dungeons. There are traitors to the idea of Bangladesh and the spirit of 1971 in Bangladesh, but they are not the ones the state and its pet mobs wish to lynch.●

Ikhtisad Ahmed (@ikhtisad) is a Stockholm-based writer focusing on sociopolitical issues in his fiction, nonfiction and poetry.