For whom Section 401 tolls?

The politics of Khaleda Zia’s medical care.

The Bangladesh government’s use of a highly potent legal provision links together Sheikh Hasina’s most significant opponent along with her most significant ally (till recently). This is Section 401 of the country’s Code for Criminal Procedure (CrPC), which allows the government to “suspend” or “remit” the execution of any prison sentence.

In the case of Hasina’s ally, General Aziz Ahmed, the country’s controversial Chief of Army Staff for three years until June 2021, the provision was used in May 2019 to remit — which means to completely suspend — the life sentences of two of his brothers who were convicted in 2004 of the murder of a political opponent..

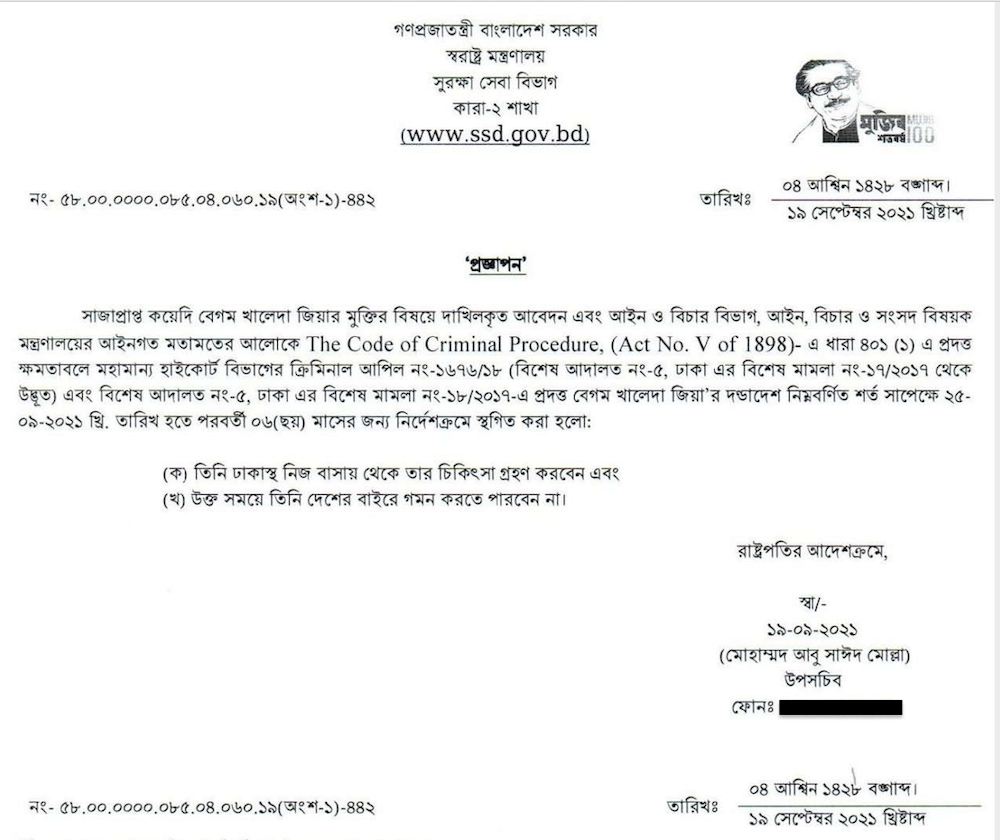

In the case of the prime minister’s opponent, Khaleda Zia, the provision was used in March 2020 to temporarily suspend her 10-year sentence for corruption, so she could access medical attention.

The existence of such powers in the hands of an executive is highly problematic — against both the rule of law and separation of power principles — as well as open to significant abuse. Following conviction, decisions to remit or suspend sentences should only be in the hands of courts. This remains an important principle even in Bangladesh where the line between executive and judicial decisions is practically non-existent: courts are so highly influenced and subordinate to the government that there is in practice little difference between the decisions the executive would like courts to make, and the judicial decisions they actually make, so that

Putting this point of principle to one side, it should come as no surprise that the government has applied this extrajudicial power far more favourably towards the prime minister’s ally than her opponent.

In relation to Aziz’s brothers, whose murder convictions were upheld in the Appellate Division, and who both absconded from justice without ever serving any time in jail, the government suspended their imprisonment fully and without conditions. For Khaleda, whose conviction remains under appeal and has been serving her sentence, the suspension is only temporary — needing to be extended every six months — and is conditional on her receiving “medical treatment at her home in Dhaka”, and not “travelling abroad.”

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party is now pressing the government to allow Khaleda Zia to leave the country on the basis that her health is deteriorating and she needs the expert assistance of medical systems abroad. She has been diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver and her doctor has said, “We don’t have the means and supportive technology… here [in Bangladesh] to control and stop re-bleeding.” He has also said that “If we want to save the life of the patient”, she needs a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, a medical procedure not available in Bangladesh.

The government has denied this request — claiming that the government has no power to intervene and that such a decision is solely in the courts.

On November 17th, the prime minister said: “I have done whatever I can for Khaleda Zia. Now the law will decide the next course of action.” On the following day, Anisul Huq the law minister told parliament that “There’s no scope in the law” to allow her, a convicted felon, to leave the country. “[The BNP] can rebuke me as much as they wish but it doesn’t matter to me. I’ll follow the law,” he said. Two days later, he doubled down on this opinion. And more recently, the foreign minister is reported to have said much the same at a meeting of ambassadors, saying that Khaleda Zia can bring in any doctors from abroad that she wants.

Yet, section 401 of the CrPC clearly provides the government the power to remit or suspend Khaleda’s sentence — under whatever conditions the government so wishes. Indeed, as noted above, the government recently just used this very provision to remit the sentence of two convicted and fugitive murderers — without any conditions at all — even when many questioned whether the power could even be used to favour fugitive convicts.

Whether the government decides to use the same powers to allow Khaleda Zia to go for medical treatment outside the country therefore has nothing to do with the courts — and all claims by the government are simply bunkum. Back in the day, the law minister, Anisul Huq was once a very credible and respected lawyer but now just appears to mouth the political lines given to him by the prime minister — a real shame.

So, just as it was a political decision by the government to release the two brothers of General Aziz Ahmed — no doubt part of a complex quid pro quo to ensure Aziz’s loyalty — it is equally one no for the government about whether to allow Khaleda Zia to go abroad.

So, what factors will Sheikh Hasina — as it is she who will make this decision — take into account in deciding whether to do so?

It is no secret that these two political leaders dislike each other intensely. Indeed Hasina holds Khaleda responsible for trying to kill her in the August, 21st 2004 grenade attacks, and for giving prestigious postings to the killers of her father and their family members. However, in deciding how to respond to the BNP request, other direct political factors will be at the fore.

Despite many years of government repression against the BNP, the party is intact and remains the country’s main opposition to the current government, with its biggest strength probably the continuing (and perhaps surprising) popularity of Khaleda Zia herself. While this does not mean that the BNP, with her as leader, would necessarily win a very-unlikely-to-happen free and fair election, it does mean that without her the BNP seems rather a busted flush.

Sheikh Hasina is therefore likely to recognise that Khaleda’s death would bring political advantages for her and the Awami League — a good reason to deny the BNP request.

However, Khaleda’s death also brings with it, in the immediate short term, a threat to the current Awami League government as it would likely trigger a reaction from BNP supporters who would congregate in large numbers on the streets of Dhaka and no doubt other places in Bangladesh. As such, Khaleda’s death is likely to be a moment of vulnerability for the current government. The question then becomes whether, for the government, it would be preferable that Khaleda dies abroad, so that the prime minister is not blamed as much for having denied her medical treatment. Either way, of course, Khaleda would (one must suppose) be buried in Bangladesh which will result in a difficult moment for the government.

Taking all these points together, one can see why the prime minister is not allowing Khaleda out of the country now; she is not on her deathbed and if she gets proper treatment now may well survive, and come back to Bangladesh a stronger leader. For the prime minister, one can surmise, the ideal situation would be to let Khaleda leave the country at a moment when her disease was sufficiently serious enough that she could not recover so that she would die abroad. This may well be why, according to BNP sources, the law minister is keeping very close tabs on the day-to-day condition of the opposition leader — to assess the right moment to consider allowing her out of the country.

While the decision about Khaleda’s departure from Bangladesh to gain medical attention should be a matter for the courts and not for the executive, the law provides the executive the power to make the decision now if it so wished. The government has very recently used this power to suspend unconditionally the sentence of fugitive murderers, and so it should be difficult for the government to justify its reluctance to use the same power in favour of its opponents that may well save a life.●

David Bergman (@TheDavidBergman) — a journalist based in Britain — is Editor, English of Netra News.