Playing to the Awami League gallery

An academic seems to contradict her own previous writing to praise Sheikh Mujib’s economic policies.

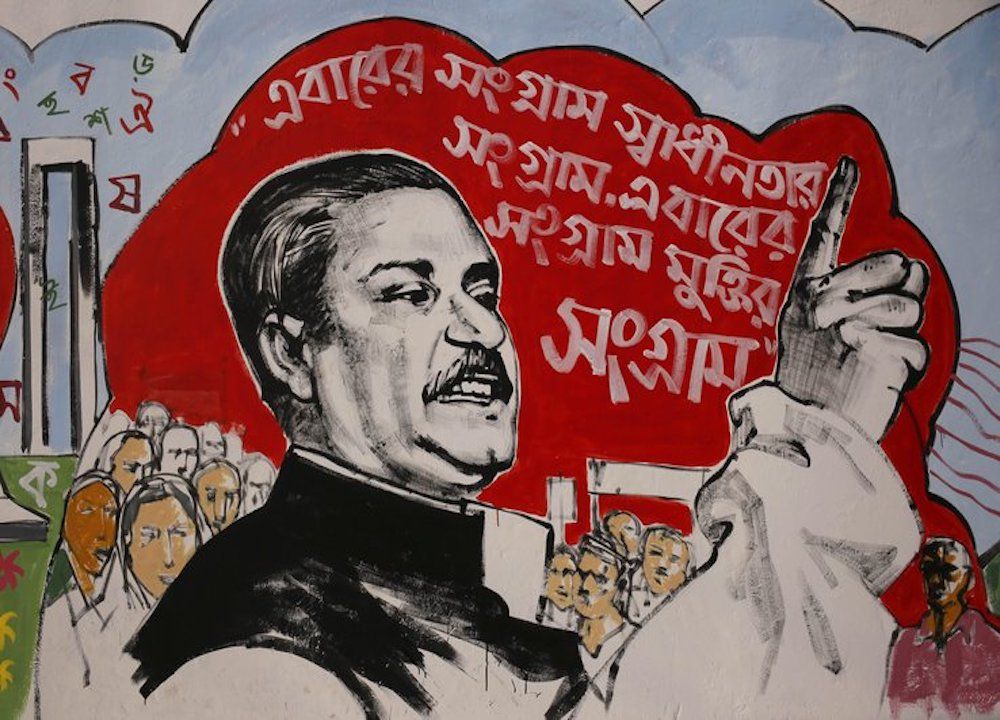

Bangladeshi political scientist Dr. Rounaq Jahan gained respect as a serious scholar with experience of teaching for decades at one of the best universities in the United States. As an academic with a PhD in political science from Harvard, her works centred on Bangladesh’s politics and governance, including the regime of the country’s first prime minister, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, between 1972 to 1975 which ended with his assassination. In 1980, Jahan authored a book, Bangladesh Politics: Problems and Issues, where she carefully analysed the governments under different leaders in Bangladesh including that of Mujib.

Throughout her academic life, Jahan has managed to maintain her political neutrality, but — along with her husband, the distinguished economist, Rehman Sobhan — she recently co-authored an article for a magazine published by the Awami League thinktank the Centre for Research and Information, which is governed by members of the prime-minister’s family.

The article, “Mujib’s economic policies and their relevance today”, published in the first edition of White Board, discusses the economic policies of the Sheikh Mujib government and their relevance in today’s Bangladesh. The opinion piece puts a positive gloss on Mujib’s economic policies and their implications, however — interestingly — it is an analysis which in some significant ways does not match Jahan’s own narrative of the Mujib regime set out in her earlier book on the period.

The myth of industrial economy’s revival

Rounaq Jahan’s article on Mujib’s economic policies claims that, “Notwithstanding the difficulties facing the CEOs of the public enterprises, most of them worked tirelessly and to the best of their capacity, at low salaries, to revive industrial activity to pre-liberation levels, thereby improving efficiency and profitability.” (emphasis added)

However, in her 1980 book, Jahan gave a very different account. On page 167 of the expanded edition, she wrote: “The regime’s performance in the economic sector was, however, far from satisfactory.” She added, “The regime fell far short of its economic goal of bringing production back to the level of 1969-70 (pre-liberation levels). Volume of trade as well as of production remained lower than 1969-70.”

Jahan indeed gave a detailed view into the matter on page 120 of the book: “Rice production in 1972-73 was about 15% lower than that of 1969-70 and industrial output in 1972-73 was 30% lower than the normal output of 1969-70. The jute industry’s output was 28% less than the 1969-70 production. Exports in 1972-73 were estimated to be 30% lower than the level achieved in 1969-70.”

In addition to that, Rounaq Jahan’s claim in the article of “improving efficiency and profitability” of the industries can be seen as inaccurate, if one looks at the figures of losses in Bangladesh’s jute industry during the Mujib regime — under Sheikh Mujib, Bangladesh’s once profitable jute industry incurred losses of 30.51 crores in 1972-73, 14.44 crores in 1973-74 and 35.61 crores in 1974-75 fiscal years.

Indeed, the academic herself commented in her book on page 167 that “the shortfall in production was linked to corrupt and inefficient management of the nationalized and public sectors.”

Top professionals or political cronies?

Then there comes the question of the appointment of the managers within the production sector. In her co-authored article for White Board, Dr. Rounaq Jahan claims that the planning commission, where Dr. Rehman Sobhan was a member, advised the Mujib government to allow professionals to run the nationalised industries and Mujib agreed to do so.

The article notes: “Mujib strongly supported such an approach and approved the appointment of some of the top professionals in the country to serve as CEOs and directors of the nationalised industries, as well as the financial, trade and transport enterprises.”

This is in stark contrast to her previous claims. In her book, she claimed: “In the nationalized sector patronage was the chief consideration in the distribution of managerial jobs and licenses for industries.”

About political patronage, she added in her book on page 149: “It was, however, the government who had control over most of the resources, i.e. seeds, fertilizers, pumps, schools etc. The MPs used their party leverage to get access to the government controlled resources and became the major channels of distributions in the districts.”

Wordy recommendations, ignoring the past

In their joint article, Dr. Rounaq Jahan and her co-author Dr. Rehman Sobhan made some recommendations which were once proposed by Mujib, citing their “relevance” to today’s Bangladesh. However, Jahan was not so positive towards the implications of these proposed policies when she had earlier wrote about them in her book.

A key part of the article’s recommendations is the introduction of cooperative-based farming. The authors found this Mujibist initiative to be relevant today though Jahan in her book stated that they did not work in the past as “the middle farmers were still suspicious of the cooperative scheme and reluctant to form it.” It is difficult to explain what has changed under the leadership of Sheikh Hasina that will make this proposal — that they suggest might need to become coercive — successful.

Ironically, Dr. Sobhan and Dr. Rounaq Jahan termed Mujib’s economic policy as “egalitarian” and suggested that the introduction of these policies would ensure that the “system works more fairly, with rule of law visibly and equitably applicable.” It is difficult to appreciate their positive view on the “rule of law” in today’s Bangladesh.

The economic policies of Mujib failed miserably. In Rounaq Jahan’s own words: “[T]he regime’s economic policies created multiple middlemen in the system and as permits were sold and resold, prices skyrocketed.”

Most of the recommendations suggested in the article had little to offer. Dr. Rounaq Jahan should re-read her own works and swallow the bitter pill that none of Mujib’s economic policies are relevant in today’s Bangladesh.●

AKM Wahiduzzaman is a Bangladeshi academic in exile in Malaysia — he is the ICT secretary of the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).

* Netra News offered Rounaq Jahan an opportunity to respond to this article but she declined to comment.