Proposed law grants Bangladesh government new powers to require people to remove social media content

If enacted, the new law could drastically increase censorship in the country.

In March 2022, Netra News published an article setting out concerns for free speech if the Bangladesh government passed into law the draft Regulation for Digital, Social Media and OTT Platforms, which the Bangladesh Telecommunications Regulatory Commission (BTRC) had posted on its website for consultation. The regulation was drafted in response to a High Court order ruling that the government should draft a law regulating social media and other similar websites.

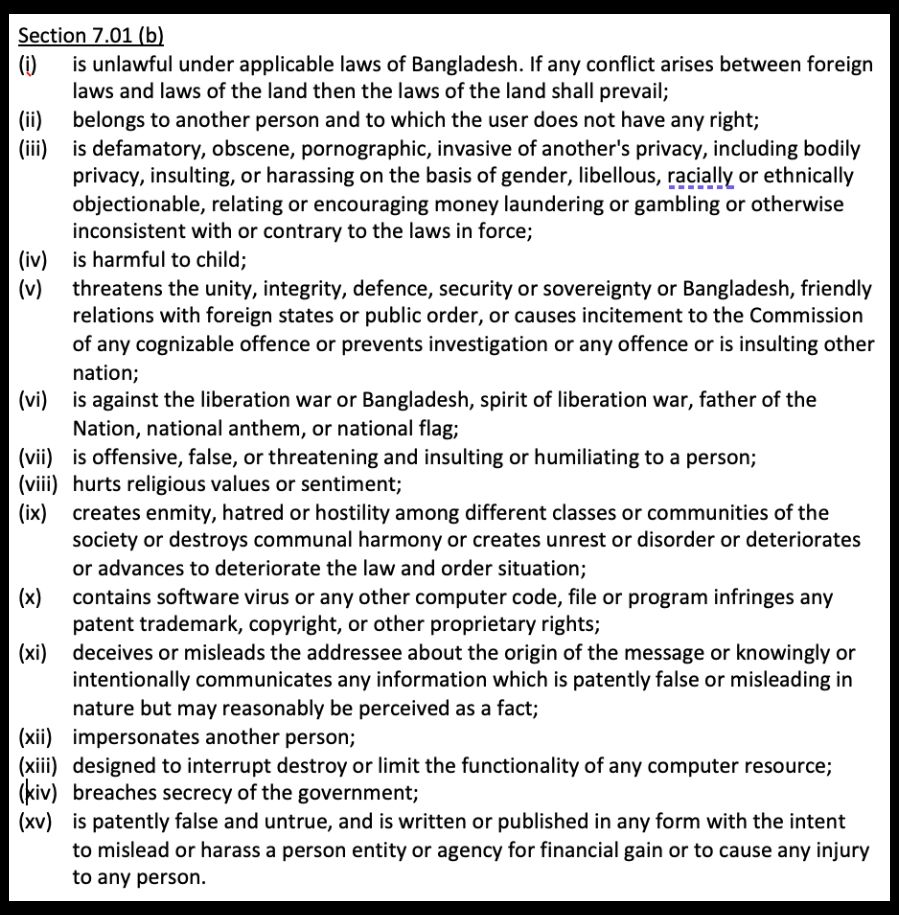

Though unclear in some specific details, the main focus of the draft regulation was to impose legal duties on social media companies so that they would have to remove wide categories of content including material that was “insulting”, “harmful”, “offensive” or “breaches secrecy of the government”. This was why the Netra News article was titled, “Bangladesh government wants Facebook to become its censor.”

The proposed regulation was pilloried by human rights organisations and others. In response BTRC revised its draft but instead of seeking further consultation submitted it directly to the court.

This new “final draft” however has received very little attention in the Bangladeshi media — but it should do as it remains alarming.

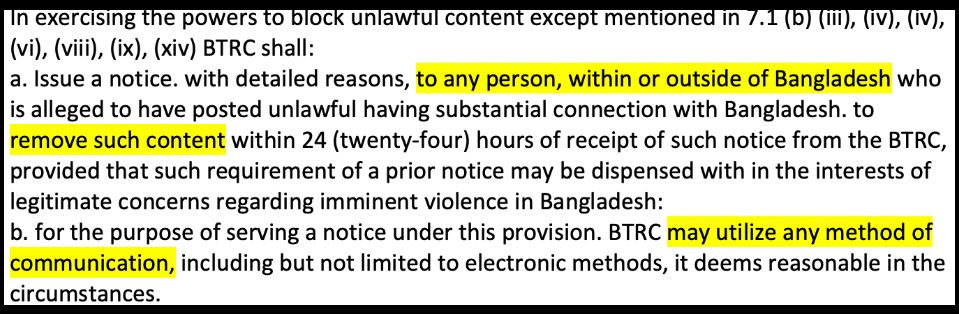

Not only does it continue to give the government the power to order social media companies to remove material on the same broad and vague categories as set out in the earlier draft, but section 12 now gives the BTRC an additional legal power to issue a notice to any person, whether they live inside or outside Bangladesh (and using any form of communiction) requiring them to remove within 24 hours certain prohibited content including material that is considered to be:

— Offensive, false or threatening and insulting or humiliating to a person;

— Unlawful under Bangladesh law;

— Patently false and untrue and is written or published in any form with the intent to mislead or harass a person, entity or agency for financial gain or to cause any injury to any person.

These kinds of terms — “offensive”, “false”, “threatening”, “insulting” or “humiliating” — which are broad and not defined, is the kind of language often used by the government and politicians to describe criticism directed at them, and so could easily be eligible under this law for a BTRC take-down notice.

The category of being “unlawful” under Bangladeshi law also effectively includes any content that could amount to an offence under the Digital Security Act. So BTRC could send notices to people who posts content it considers to be:

— Any kind of propaganda or campaign against the Liberation War of Bangladesh, the spirit of the Liberation War, the Father of the Nation, the national anthem or the national flag;

— Known to be propaganda or false, and posted with an intention to affect the image or reputation of the country, or to spread confusion.

At present, the government’s primary mechanism of stopping people from posting such material is through arrests under the Digital Security Act which are followed by long periods of pre-trial detention. This allows the government to force the relevant person to remove the offending material, punish him or her for posting it, and send a strong message to others not to do something similar.

For obvious reasons, this criminal justice approach has been subject to significant criticism. Imprisoning people for what amounts, in functioning democracies at least, to legitimate criticism is draconian and repressive. Moreover, there are only so many people that can be prosecuted in this way.

This new power to issue notices directly to users requiring them to remove material would be far less time consuming, can be done without public attention, does not require a notice to be sent to the social media companies, and does not come with all the criticisms that arise from arresting and detaining people. It could also be a far more effective way in getting posts removed. Although failing to comply with a notice is not in itself a criminal offence, people receiving one are quite likely to be fearful that if they do not comply, they could anyway be arrested under the Digital Security Act — so are more likely to take down the material.

The BTRC can also forego with the 24 hours notice if it has "legitimate concerns regarding imminent violence in Bangladesh."

In tandem with the powers that the BTRC regulation also gives the government to order social media networks to remove material, this additional new power directed at social media users themselves would almost certainly result in even greater tightening of freedom of expression on social media in Bangladesh resulting in far less political criticism than is present.

However, it may not come to that.

It is difficult to see how this new regulation complies with Bangladesh's constitutional right to freedom of expression set out in Article 39. This only allows the government to restrict freedom of expression in certain limited circumstances — in the interests of the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence. It does not allow the government to restrict speech for many of the reasons it seeks to do so in the BTRC regulation. However, whether the courts and judges have the strength and independence to rule against the government, in a matter like this, is another question entirely.●