Secret prisoners of Dhaka

Survivors blow the lid off a secret prison operated by the DGFI, Bangladesh’s notorious military intelligence agency.

On May 29th 2016, Shekh Mohammad Salim was waiting at an auto repair shop in Kapashia, Gazipur, as technicians were renovating a bus owned by his family. This was something he took a great interest in, coming from a family in the transportation business.

His undivided attention was soon disrupted by a microbus’s sudden arrival. A group of four to five men got out, with one of them holding a strange-looking device with a monitor. The cell phone in Salim’s pocket began to vibrate, indicating an incoming call. He reached into his pocket to pull out his phone, and the men nearby knew they had found their target.

“Are you Shekh Mohammad Salim?” asked one of them.

Not knowing any better, he nodded positively. The men then grabbed his hands and forced him into the microbus, with his hands cuffed behind his back and eyes covered with a blindfold.

Salim had no idea who his captors were, let alone why he was being picked up. But soon, he would be an inmate of an illegal secret prison, codenamed Aynaghar (House of Mirrors), run by the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), Bangladesh’s notorious military intelligence agency.

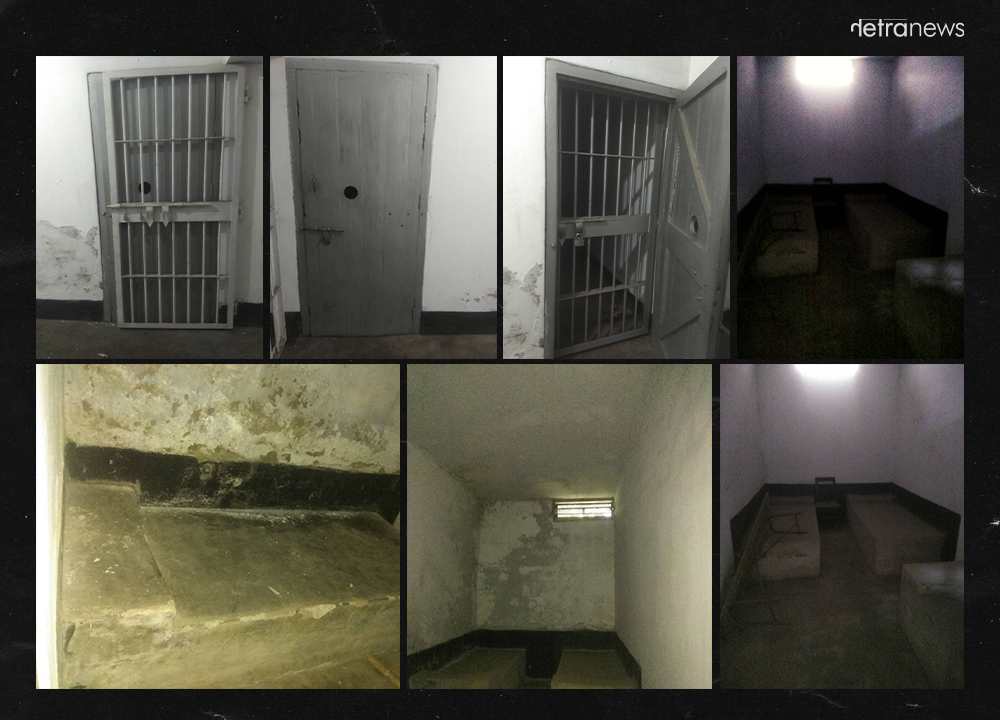

For the first time, two former inmates — including a former military officer — have come forward publicly to describe the features of this secret prison. In addition, two current military officers not only confirmed the prison’s existence but also provided Netra News with photographs of the tiny, cramped cells inside it. We have also obtained satellite imagery from Maxar Technologies to corroborate and even pinpoint the location of the facility.

Since 2009, as the Bangladesh Awami League returned to power, enforced disappearances have become a brutally effective weapon in the government’s arsenal of repression. According to a tally maintained by the rights group Odhikar, at least 605 individuals became victims of enforced disappearance in Bangladesh between 2009 and September 2021. The list includes terrorism suspects, alleged criminals, political opponents, critics of the ruling party, as well as ordinary people like Salim. Human Rights Watch has published a list of 86 men whom they claim have been picked up over a ten-year period, whose whereabouts remain unknown and who are suspected of still being in secret state detention or killed.

Our investigation into Aynaghar suggests that this particular facility is principally used to incarcerate “high-value detainees”. However, Salim was no “high value” captive — but rather an intriguing case of mistaken identity.

Salim in Aynaghar

A native of Kapashiya, Salim comes from a family of commercial car and bus owners. Before leaving for Malaysia a few years ago, he drove commercial vehicles between Dhaka and Gazipur. So when the microbus carrying him reached Rajendrapur rail crossing and crossed the army check posts inside Rajendrapur military cantonment, despite his blindfold, he guessed the route (Rajendrapur-Gazipur-Dhaka) and rough location of the place he was being driven to.

When he was finally let out of the microbus, he heard the sound of a collapsible gate being opened. His captors then made him walk down the stairs to a windowless room. A doctor came to check his blood pressure and do a medical checkup. He was then taken to a cell.

Salim provided us with some key details about the place of his secret detention, including the kind of snacks he was given (e.g., Energy Plus biscuits) and the brand of mineral water (Mum) he drank. The place had some loud exhaust fans running nearly 24/7 to drown out all other sounds. Because of vibrations felt within the building, he also guessed that a plane landed or took off regularly at a nearby airport or airfield.

Past inmates had also provided him with further clues about the identity of their common captors. On the walls of his cell, many had carved out the agency’s name — DGFI — using leftover bones from meals or some such objects.

“I could not even imagine how many people had been locked in this prison before me,” Salim told Netra News in a recent interview from Malaysia. “Handwriting styles are different from one another. Someone wrote, ‘DGFI brought me here,’ while another person wrote, ‘DGFI arrested me from my home.’ Some even carved the mobile phone number of their family members, urging, ‘please ask my family not to stop searching for me, and tell them that the government brought me here.’”

But that only confounded Salim’s confusion: why on earth would DGFI detain him?

Hasinur Rahman in Aynaghar

In contrast, Hasinur Rahman, a former lieutenant colonel with the Bangladesh Army, had little doubt about his “high value” status when he was detained on August 8th 2018—his second stint as a victim of enforced disappearance (the first time he became a victim of enforced disappearance was in July 2011).

He was a decorated military officer who had been accorded the title “Bir Pratik”, a major military gallantry award. A former commander of a RAB unit, Hasinur Rahman also led several anti-militancy operations. But in 2012, after 28 years in the service, he was sacked on the vague allegation that he had been involved with militancy himself—a charge he strongly denies.

The men who captured him from his house in 2018 at Mirpur Defence Officers’ Housing Society (DOHS), a residential area for current and former military officers, wore the jackets of the Detective Branch (DB), according to family members. (DGFI does not have any legal authority to detain people—its members often assume the identities of civilian agencies such as DB when they carry out abduction operations).

After being picked up in August 2018, he went “missing” for eighteen months. When he was released in February 2020, after one year, six months, and fourteen days in secret detention, he—like many other victims of enforced disappearance before him—declined to provide details about his disappearance. In recent months, he has become more outspoken on social media. When a Netra News editor approached him for an interview, he agreed to provide fresh details about his disappearance.

Unlike Salim, Hasinur Rahman was a military insider and could point to specific and precise details of the secret prison: “To the north is the 14-storey building [DGFI headquarters]. To the south is Mess B. Between them is a field; in the middle of the field [is the prison]. The Logistics Area Headquarters, Station Headquarters, and ENC (Engineer-in-Chief) Office are to the south of the field. To the west is an MT shed—DGFI’s MT shed—and to the northeast is DGFI’s mosque. This house of disappearance is called Aynaghar.”

The crucial details provided by Hasinur enabled Netra News to geolocate the facility. Recent Google Earth satellite imagery shows that the roof of the building is now covered with tarpaulin. Rahman himself visited a nearby building recently and confirmed that the building was indeed covered.

Netra News has, however, been able to obtain archived satellite images of the facility from Maxar Satellite that matched the descriptions Rahman provided.

Strikingly similar descriptions

In recent months, Salim approached Netra News to tell his story. When he disappeared in May 2016, his brother filed a general diary with the local police in Gazipur. An old newspaper clip we obtained from the archives says that he had been abducted or gone missing.

However, Salim was not the person his captors wanted to detain. They soon realised that they had got the wrong man. He was then released, but only after a fake criminal case was filed against him. He was handed over to the Detective Branch (DB) of police, which showed him as “arrested” on cooked-up charges and presented him before a court. A few months later, he was released on bail. Soon thereafter, he returned to Malaysia.

Netra News shared Salim’s descriptions of the secret prison with a group of officers working with different law enforcement and security agencies, including RAB, DGFI, and DB. Two of them recognised the facility based on Salim’s descriptions. It was these two officers who first told us the codename of the prison: Aynaghar.

According to one of them, the facility has more than 30 holding cells and several soundproof interrogation rooms, where detainees are often tortured. They also provided us with a list of current and former detainees of Aynaghar. One of the former detainees on that list is Hasinur Rahman.

“I served in Dhaka before. I was an ops officer with the military police. Therefore, I immediately recognised the area and even the location [of the secret site],” Hasinur told Netra News in a recorded interview. “There was a new section built within the house, which had five plus five [10] rooms. In one of the toilets [in the new section], there was a high commode toilet. I got up on the toilet and peered out through the exhaust fan, and I recognised the old buildings and the surrounding area.”

He further explained that the building has two sections—the old one has 16 rooms, while the new one has 10. The guards working at the facility are both civilian and military.

Hasinur Rahman and Shekh Mohammad Salim, who did not know each other, provided strikingly similar descriptions of their former prison. Like Salim, Hasinur also said that the captors at times gave him “Energy Plus” biscuits. Both the former detainees said the quality of food provided to them was excellent, and “Mum” water bottles were provided. Salim could guess that there was an airfield where aircraft often landed, but Hasinur Rahman could definitively say that it was the runway of the nearby Tejgaon Airport, which was used by routine aircraft or air force and army aviation planes.

“When the exhaust fan that causes massive sound was turned off, I could hear other people cry. When it was turned on, the sound was so loud that I would not hear anything else,” Salim said.

“Several huge exhaust fans were installed at the facility to make it soundproof. For example, the new ten rooms of the facility share four exhaust fans so that no sound comes inside or goes outside,” said Hasinur Rahman.

They also provided similar descriptions of the holding cells’ features: that there were no windows, that the ceiling was too high from the ground floor, and that the rooms had two doors—one was a prison-like iron door, the other a wooden door with a hole in it.

One of the military officers who earlier corroborated the existence of Aynaghar provided us with several photographs of the cells, which matched the descriptions provided by Salim and Hasinur.

The officer confirmed that DGFI’s Counter-terrorism Intelligence Bureau (CTIB) was responsible for maintaining the facility. Since 2016, four officials with the rank of brigadier general have served as the director of CTIB, while four officers with the rank of major general have served as DGFI’s director general.

The list of names of former and current detainees of Aynaghar that was provided to us includes Mubashar Hasan, formerly a professor at North South University, whose disappearance was reported by The Wire, an Indian news website, to have been orchestrated by the DGFI. Former ambassador Maruf Zaman, himself a former military officer, and businessman Aniruddha Kumar Roy were also detained in Aynaghar.

Current detainees include two men picked up by law enforcement authorities in August 2016: Mir Ahmed Bin Quasem, the son of Mir Quasem Ali, the Jamaat-e-Islami leader who had been sentenced to death by the International Crimes Tribunal, and Abdullahil Amaan Azmi, a former military general and the son of Ghulam Azam, former Jamaat-e-Islami chief who had been sentenced to life by the same tribunal.

Two officers who saw these two men in Aynaghar confirmed the sightings to Netra News. On one occasion, Hasinur Rahman, too, saw Azmi at one of the toilets at Aynaghar, due to confusion among the guards who were in charge of taking the detainees for scheduled toilet visits. Hasinur also subsequently confirmed Azmi’s status as an inmate of Aynaghar through one of the civilian guards he cultivated inside the prison.

“Liton of Badda”

While Hasinur, as a former military officer, was treated with respect compared to other inmates, Salim was not. He would often be beaten and tortured.

“One day, they beat me up severely and then took me to a different cell,” he recalled. “The room was unusually heated. I soon noticed there was another inmate. He was silent. When I asked him about his identity, he would not respond. At one point, he simply said, ‘My name is Liton. I am from Badda (a neighbourhood in Dhaka).’ So he was known to me as Liton of Badda.”

“Liton was also a martial arts or karate trainer. He was even slated to participate in the Olympics [as part of the Bangladesh squad],” added Salim.

Based on his description, Netra News was able to identify another detainee of the secret prison. Liton of Badda was, in fact, Sheikh Mohammad Abu Saleh, who was a karate trainer in a school in Dhaka. RAB, the elite police unit run by military officers, “detained” him in November 2016, alleging that he had been involved in militancy and terrorism-related offences.

When we provided Salim with Abu Saleh’s photo, he confirmed that the photographed man was indeed Liton of Badda whom he had seen at Aynaghar. In other words, the RAB staged a fake “arrest” of Abu Saleh aka Liton alias Huraira, which they touted as their anti-terrorism success.

An English-medium school teacher

“Once a day, the loud exhaust fan would cease to operate for 30–40 minutes. At that time, it would seem that you were beyond any earthly dimension—there was no sound. It felt like a void,” Salim recalled. “That was when Liton would talk to another person in the next room.”

“Once the sound stopped, they would knock on the wall to draw each other’s attention. The other person, through Liton, requested that I call his mother if I got released. He had already carved his mother’s mobile phone number on the walls of the toilets. He asked me to call his mother once I was released.

“He asked me to tell her that he was imprisoned somewhere near Kafrul (in Dhaka), and that she should contact the high-ups of the government for his release. Liton told me that [the person in the next room] was a teacher of an English-medium school,” Salim added.

“I was not courageous enough to call the number right after I was released. But I did call her when I was out of the country,” Salim said. “His mother cried and warned me that I would be in trouble for calling her because all her family mobile phone numbers were being intercepted. But I assured her that I was in Malaysia.”

Two Netra News reporters called the same number. The woman who responded was Mumtaz Karim, the mother of Tehzeeb Karim, an English-medium school teacher who went missing from Dhaka Airport in May 2016.

Three years later, in May 2019, he would be presented before a court on the charges that he had been involved with terrorism. Tehzeeb’s brother Rajib Karim had already been implicated in terrorism charges in the United Kingdom.

Tehzeeb’s case, too, confirms the pattern that suspects or individuals are picked up by security agencies, kept in a secret prison for months or years without acknowledgement, violating legal procedures, and then presented before a court as if they had just been arrested.

Subsequent bogus charges

Shekh Mohammad Salim was also produced before a court in August 2016 under a charge that he was a member of a proscribed terrorist organisation in Bangladesh. While Tehzeeb’s case may have some merit, Netra News was able to confirm that charges against Salim were bogus.

“One day, just after dawn, they took me to an interrogation room blindfolded. A woman began the interrogation with simple questions. ‘What’s your name?’ she asked. ‘Shekh Mohammad Salim,’ I responded,” he recalled. “She then asked the name of my father. I answered correctly, but she repeated the same question over and over again.”

“They also could not accept my date of birth. Suddenly, they started beating me. Several people beat me up right and left. I cried out loud. Then they asked me about a locality in Gopalganj—perhaps Kotoalipara,” he said as he struggled to recall.

“They then claimed I placed bombs in Kotoalipara to kill Sheikh Hasina. I was stunned! I said I had never been to the place. They also could not accept that I was from Kapashiya in Gazipur,” he said.

Based on the interrogators’ questions, Netra News assessed that his detention was likely a case of mistaken identity. The agency was likely interested in a person who used the alias “Selim” and was accused of planting bombs in Kotalipara—not ‘Kotoalipara’, as Salim mistakenly understood—to kill Sheikh Hasina.

In February 2021, a man named Iqbal Hossain was shown arrested by RAB, which told reporters that he was a member of Harkatul Jihad, a banned militant group; that he was involved in the grenade attack in an Awami League rally on August 21st 2004; that his alias was “Selim”; and that he had been in hiding in Malaysia. To detain him, RAB carried out several raids in Savar and Gazipur.

It was likely that in a bid to detain Iqbal Hossain alias “Selim”, DGFI managed to detain Sheikh Mohammad Salim instead. When they realised they had made a mistake, they transferred him to the Detective Branch of the police, which presented him before a court with false charges.

Salim provided other crucial clues, which have allowed Netra News to reconstruct how the Counter Terrorism and Transnational Crime (CTTC) unit of Dhaka Metropolitan Police staged a fake gunfight to kill young men in a false-flag operation.

Reactions

“In our work on enforced disappearances, obviously, we have known that there are these secret sites. It is still devastating to know that they exist and that they exist with the full knowledge of the military, in the military compound,” Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia Director of Human Rights Watch, said of the findings. “And we hope that, very quickly now, there is an investigation, not only on this site but on others. The people that have been held here—and many have been held for years, and their families are still waiting for them to come home—should be immediately released. And then there should be a proper investigation into who’s responsible.”

Netra News contacted the spokesperson of DGFI for the agency’s response to our findings and sent him a questionnaire containing the allegations noted in this story; we did not receive his comments.●

Journalist Zulkarnain Saer Khan contributed to this story.

[The text was slightly edited to remove certain ambiguities.]