The Shakedown of Yunus

Bangladeshi anti-corruption agency’s new allegations of money laundering and coercion indicate how the government still views the Nobel Peace Prize winner as a threat.

In a country where money laundering and corruption are so rife, Bangladesh government’s Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) decided in August to investigate arguably one of the most transparent people in the country, the Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank.

Thanks to this government, Yunus is also one of the country’s most heavily investigated people. Bangladesh Financial Investigation Unit (BFIU) has on multiple occasions enquired into his bank accounts and tax affairs. This though is the first time the ACC has got involved resulting in increased jeopardy.

On August 3rd 2022, the ACC sent a letter to him and other board members of Grameen Telecom (GT), a private non-profit company with significant stakes in the country’s largest mobile operator Grameenphone, stating that it was investigating allegations that GT had laundered $314 million (Taka 2,977 crore), misappropriated $4.8 million (Taka 45.5 crore), and illegally taken, “in the name of advocate fees,” a figure which would amount to over $2 million (over Taka 19 crore)*. It asked the company, chaired by the famed Grameen Bank founder, to provide it with detailed documents going back to when the company was first established 25 years ago. Since then, the managing director of Grameen Telecom was questioned by the commission over the alleged money laundering and misappropriation.

The allegations are very serious and raise obvious questions. Have we misjudged Yunus, so that he is not the incorruptible person that he was widely believed to be? Or, alternatively, is this just yet more bogus government-sponsored investigations seeking to harass and intimidate him, as well as possibly being a pretext to take control of the company?

Hasina and Yunus

Muhammad Yunus has long been a bete noir of the prime minister. The story goes that, in 1997, during her first ever term in government, Sheikh Hasina strongly believed that she should have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her role in brokering the Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord. When Yunus won the prize nine years later for his role in establishing the microcredit body Grameen Bank, Hasina’s nose was seriously put out of joint.

However it was his announcement in February 2007, that he was planning to establish a new political party, which helps fully explain Hasina’s antagonistic relationship with Yunus. This was a year after he had received the peace prize, and a month after the military took over power to thwart the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) holding a rigged election. The Awami League initially welcomed the decision, but the party soon realised that the military wanted to displace the existing party duopoly and encourage the formation of another political party, perhaps with the Grameen Bank founder as its head.

Yunus initially warmed to the idea of getting involved in politics, writing an open letter asking for people's views on whether he should do so. Though Yunus announced two months later that he would not proceed with the initiative, from then on Hasina saw him as a political threat and enemy and the incident transformed her own personal jealousy towards him into a wider grievance shared by her party, the Awami League.

With Hasina’s party winning the subsequent 2008 elections, the government made Yunus one of the government’s premium targets — removing him from his position of managing director of Grameen Bank in 2011, promoting a defamatory media campaign against him and subjecting him to wide ranging financial investigations and inquiries over the next few years — all of which came to nothing.

In the decade since then, the government has tried to make Yunus’s life as difficult as possible, often hindering or preventing his various projects from getting off the ground, filing criminal and other cases against him and his companies, and every so often launching a rhetorical broadside against him. This playbook, arguably, is no longer about punishment for Yunus’ earlier plans to set up a party aiming to displace the Awami League, but to ensure that he is defamed sufficiently so that he is no longer a threat to the prime minister and that neither he, nor anyone else, ever thinks again of challenging her .

The investigation, and the “$314 million laundering” claim

Fast forward to this investigation.

Bangladesh’s ACC is supposedly an independent institution, but it is only independent in the same way that the police, the Election Commission or the courts are claimed to be — meaning not very independent at all.

The ACC generally does exactly what the government or its officials ask it to do and its decisions to initiate this inquiry against Yunus quickly followed on from a speech in parliament where Sheikh Hasina accused the founder of Grameen Bank of all kinds of corruption and political meddling.

This time around the target is Grameen Telecom (GT), a not-for-profit company set up by Yunus in 1995. No longer with a role in Grameen Bank, this company has become central to the Nobel Peace Prize winner’s current work in Bangladesh. This is because the company holds 35% of the shares of Bangladesh’s first and biggest mobile phone company, Grameenphone, which allows it to receive substantial annual dividends which he, along with the other board members, use to fund numerous high value social projects.

In its recent letter, the ACC’s most serious allegation is that Yunus along with the other GT board directors are involved in the laundering of $314 million of the company’s money. This is obviously an extraordinarily serious allegation, and had Yunus and others been involved in doing what is alleged, it would place him at the heart of a serious crime.

It, however, does not require too much enquiry to realise that there is no basis at all to this claim.

Grameenphone, the mobile phone network, was set up in 1997 and is majority owned by the Norwegian company, Telenor. Grameen Telecom, the not-for-profit company which Yunus established and chairs, became a major shareholder in Grameenphone through a $10.6 million loan in 1999 from the Soros Economic Development Fund, now part of the Open Society Foundation run by the billionaire philanthropist George Soros.

In the immediate years after Grameenphone was established, when mobile phones were a rarity in rural areas, GT’s main project was the establishment of the Village Phone Project whose purpose was to allow disadvantaged women to earn an income by selling telephone services around their neighbourhood. This became an award-winning initiative that helped ensure that the advantages of mobile phones were widely harnessed by all sections of society at an early stage in their introduction to the country.

In 2003, Grameenphone started to pay out dividends to its shareholders and since then GT has received a third of all the mobile company’s annual payments, giving the company a very healthy balance sheet indeed. In the 11 years since 2011, Grameenphone’s annual reports indicate that this amounted to, just over $1 billion (over Taka 9,517 crore), an average of around $90 million per year, pre-tax. GT’s own records show that since 2003, after tax, the dividends since 2003 have totalled $919 million (Taka 8,735 crore)

As the dividends started to arrive, the not-for-profit company began to use its income to establish large numbers of social businesses — through loans, equity finance and donations. This has resulted in, for example, the development of Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing into the country’s biggest private nursing college, establishing four eye care hospitals and 150 primary health care clinics around Bangladesh, and setting up a company that has installed 40% of the country’s solar home systems and much much more. The businesses set up to implement these projects have been established either as not-for-profit companies or as companies whose memorandum of association do not allow its shareholders to remove any profit from the company (other than the return of any original principal invested) which must, instead, be reinvested. Yunus is the chair of most of these companies.

The key to understanding all this is that GT — and the other companies that GT funds — are not-for-profit entities. The directors, including Yunus, are not shareholders and they do not, as a result, share in any surplus income obtained from their activities. This money, instead, is kept in the company ready to be reinvested in existing or new social projects. In fact, according to GT, no directors, including Yunus, even receive any honorarium for taking part in board meetings.

So what exactly is the $314 million (Taka 2,977 crore) which Yunus and others are accused of laundering?

This figure refers to the amount of money which GT has invested directly into its social businesses — though the actual figure, according to GT’s own records, is $363 million (Taka 3,453 crore). The lower figure of $314 million was, apparently mistakenly, given to the Inspectorate of Factories by the company’s union, who in turn seem to have passed it onto the ACC.

It is completely unclear how anything that GT has done, in funding social projects, where there is no iota of evidence that directors gained any financial benefit, can amount to a crime. It can not even be argued that these social projects are outside the “objects” set out in the company’s memorandum of association, as this included, for example: “to promote, aid, guide, organise, plan, develop and coordinate projects/ schemes aimed at all round development and help in creation of productive employment opportunities, promotion of self-reliance and generation of awareness for improvement in the quality of life of the poor.”

It is embarrassing that the country’s anti-corruption agency, the ACC, cannot understand that the investment by a not-for profit company into Bangladesh-based social projects, which are permitted by the company’s objects, is as far away from the offence of money laundering as could possibly be. It only serves to show how this bogus inquiry is simply another act of political intimidation.

Other alleged misappropriation

In the letter, the ACC also claims the GT’s board of directors are involved in alleged misappropriation of $4.8 million (Taka 45.5 crore), and the illegal taking of millions of dollars “in the name of advocate fees.”

These allegations, which are equally sham, require consideration of provisions in the country’s 2006 labour law that requires that 5% of the profits of a company should be placed in various funds set up by the company: 80% (of the 5%) should be given to a “workers participation fund” and distributed among its employees; 10% should be placed in a “workers welfare fund” run by the company; and the remaining 10% should be given to the government in its own “Workers Welfare Foundation Fund”.

This was relevant to GT as the company also employed workers. This is because through the Village Phone programme, they became a nationwide distributor of Nokia phones hiring as many as 300 people at one time, though in recent years that number had decreased to around 60.

GT’s board, on the advice of its lawyers, did not however believe that these Labour Law welfare provisions applied to it, arguing it was a not-for-profit company, so no “profit” could be distributed. However in 2017, former employees of the company began filing cases in the Labour court claiming not only that GT owed them money from the participation fund, but that in calculating what was owed to them, the annual dividend GT received from Grameenphone should be included as “profits” of the company. That would mean that a large proportion of 5% of the millions of dollars of dividends received each year should be distributed among the few hundred workers

GT’s position was that if the court was of the view that the 5% of profits of the company should be paid to the workers, it should certainly not include a proportion of the Grameenphone dividends. As far as the company was concerned, GT employees did not work for Grameenphone; they were not on Grameenphone's payroll; and they played no role in generating profit for Grameenphone and so should not have a share in it.

In 2019, the Inspectorate of Factories itself became involved and filed a criminal case claiming that Yunus and other company officials were in breach of a number of labour law obligations, including not paying the workers from the Participation Fund. This case remains ongoing, though Yunus is seeking to quash this case against him at the High Court.

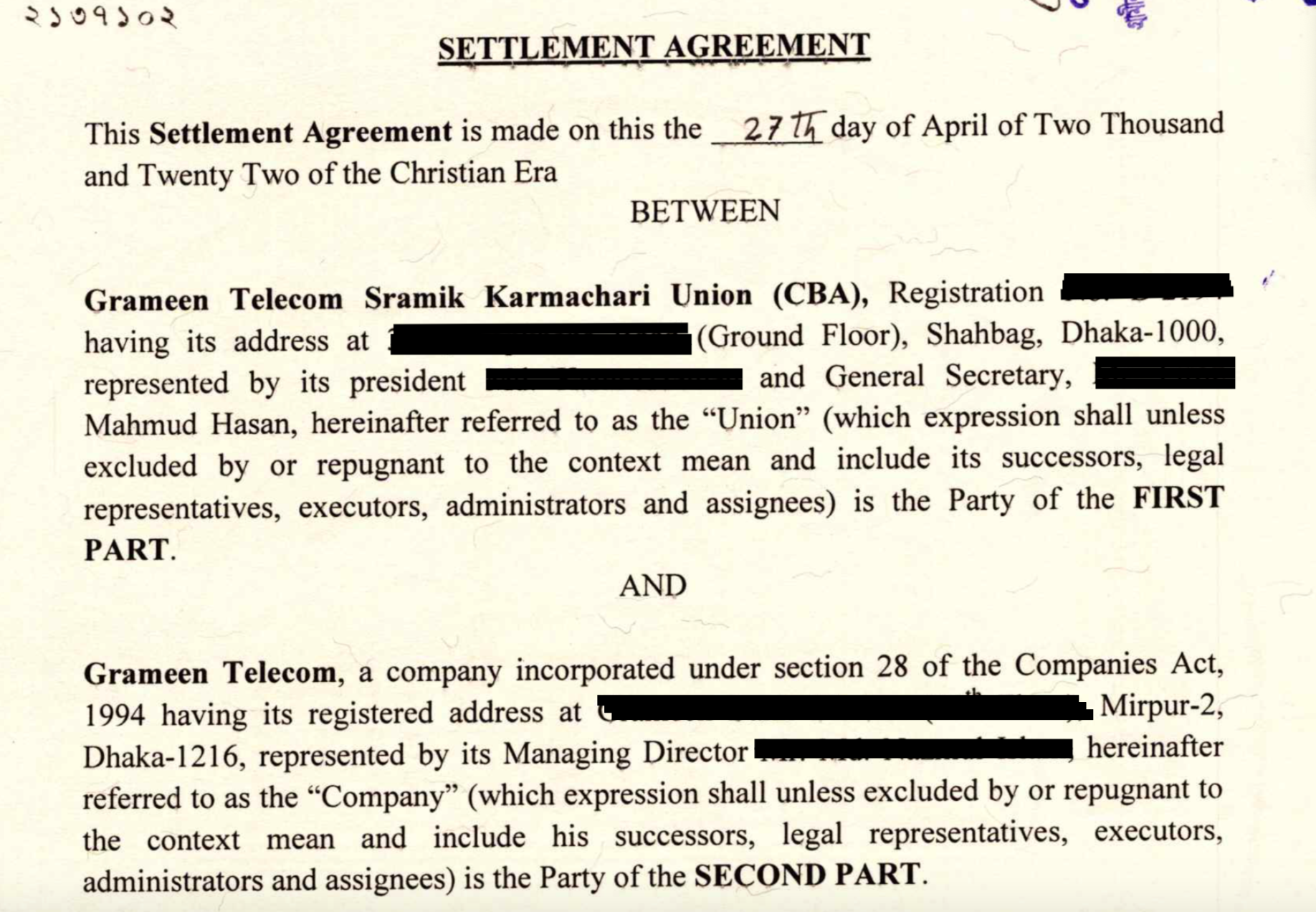

As these proceedings were going on, the Grameen Telecom Sramik Karmachari Union — comprising of workers from the company — sought to increase the pressure on GT and filed a petition in the company court requesting it to “wind up” the company arguing that since the Nokia business had come to an end, the GT was no longer active. In April, the Company Court admitted the case and started the process of liquidation.

The spectre of the court deciding to wind up the company — even though its main activity was the disbursement of funds to social businesses which were continuing— focused the minds of GT’s board and they quickly decided to agree to pay the outstanding labour welfare claims as demanded by the union. Liquidation of the company would not only have impacted upon the funds it held, but also on Grameenphone itself, since GT was a major shareholder with directors on its board.

Under the agreement with the union, seen by Netra News, which was signed by both parties on April 27th 2022, the company agreed to pay “90% of 5% of its net profit before tax with 4% interest for the years of 2010 to 2021-2022” into a “settlement account… within seven working days”. This included both the money in the participation fund and in the company’s welfare fund and according to the settlement amounted to a total of $46 million (Taka 437 crore). However, the amount paid into the account was $43 million (Tk 409 crore) as, according to the GT, both parties realised that a mistake had been made in the interest calculations. “The union has provided the company with letters of authority signed by all the members authorizing the union to enter into this agreement on their behalf at the time of signing this agreement", the agreement reads.

The settlement account, according to the agreement, was managed by two union and one company representatives, but was controlled by the union. “The concerned company representative shall put his signature to the respective cheques/ Electronic Fund Transaction instruction as represented by the union,” it noted. The agreement adds that “the company and the union shall determine the amount payable to each individual member of the union by taking into account the entitlement of each member as per length and duration of the service…”

This was in effect a total financial victory for the union and workers. In return, the union and workers agreed to withdraw all their cases filed in the labour and company courts and resign from their jobs.

This money was shared between a total of 164 current and former employees, which meant that on average each worker would have received an average of $262,000 (Taka 2.5 crore), with the amount each worker received commensurate with the number of years of employment. This was an extraordinary payday for these workers.

This figure includes both the 80% Participation Fund money and, as noted above, the 10% Workers Welfare Fund money which alone amounted to $4.8 million (Taka 45.5 crore). The ACC is alleging that this $4.8 million — part of the money given to the workers in the settlement — was misappropriated. There is simply no rationale for such an allegation. It was paid to the workers as part of the settlement.

The ACC is also alleging that 6% of the total money given to the workers was “misappropriated”. On the basis of the actual amount given to the workers, $43 million (Taka 409 crore), this would be $2.3 million (Taka 24.5 crore) - but according to GT, the union demanded that the amount be $2.7 million (Taka 26.22 crore) 6% of the $46 million (Taka 437 crore), the figure which was written into the settlement. But there is no misappropriation here. This figure comprises an amount that the union paid its lawyer to cover its legal costs and also to cover its own administrative costs. This money was not paid by the company — the money came from the amount that it owed the workers. So after GT paid all the money it owed into the settlement account, each worker had 6% discounted from the specific amount that was owed to them to pay for these expenses.

New allegations of coercion

There are now new allegations against the board of Grameen Telecom, perhaps even more tortuous than the other inaccurate claims, involving the suggestion that the company coerced the trade union to agree to a settlement by giving them bribes. It comes after a number of the union leaders were arrested.

To appreciate the absurdity of this new claim, let's review the situation.

The union/workers demanded that each employee be paid a share of the “participation fund”, and that in calculating what was owed, the dividends received from Grameenphone should be included in the calculation. The company refused arguing that the law did not apply to not-for-profit companies like itself, and that even if it did, calculations of what was owed should not include its dividends. The government’s Inspectorate of Factories also filed a case against GT. The union then filed a case in the Company Court, which placed GT’s existence at risk. As a result the company agreed to pay the workers on the basis that they demanded. A settlement was agreed that complied with the letter of the law as interpreted by the union. Clearly, if any party was coerced into the agreement, it was GT.

So where does the claim about so-called corporate coercion come from?

As mentioned above, Taka 26.2 crore — equivalent to 6% of the total amount owed to the workers — was deducted from the total and given to the union to cover their legal and administrative expenses. It is supposedly this money that was given as a bribe to the union to agree to settle the case.

This is indeed a sizeable sum of money, and the lawyer apparently was paid a very large amount indeed. Although this fee may be indecent to some, if it was agreed by the union and the workers, it is not criminal. But more significantly, in the case of this ACC investigation, this was not GT money. The Taka 26.2 crore all came out of the money that was allotted to the workers, and it was their decision that the money be deducted from the total.

But, in any case, what could it have been a bribe for exactly? The purpose of the workers’ original legal action was to get what they thought was owed to them in law. The settlement did exactly that, and it could not have been more generous. So why would the workers or the union need to be bribed to agree to a settlement that gave them everything they wanted.

Surely, this could not be because the government would have preferred for there to have been no agreement and for GT to have been liquidated?

And so…

There are many people, particularly those linked to the country’s opposition parties, who are or have been held in the Bangladesh jails for no legitimate reason other than for the political convenience of the current government. Its control of the police and the courts provides the authorities with the ability to lock up those people it wishes.

The government cannot do this so easily in relation to Yunus as unlike others he is protected by his Nobel Peace Prize as well as his stellar international reputation. The government will only ever be able to get away with imprisoning Yunus if it had a very strong provable evidence-based rationale, which is absent despite their years of looking.

In the meantime, these current investigations serve to harass and intimidate Yunus, seeking to make him a controversial figure and, in the eyes of the prime minister, less of a threat to her, which is in effect the government’s ultimate objective.

They also possibly serve another purpose. The government (and the Awami League) would no doubt love to get its hand on the the Grameenphone dividends which are given to Grameen Telecom, and these investigations might be part of their attempt to wrest control of them away from the Nobel Peace Prize winner and the other directors of the not-for-profit company.●

* All figures originally in Taka, and current exchange rates have been used

Correction: the text has been corrected to clarify that from the money that was paid to the workers, Taka 26.22 crore was paid to the union as legal/admin expenses, not Taka 24.5 crore. Also, the text has been corrected to show that Yunus resigned as managing director of Grameen Bank in 2011.