The truth about the UN working group on enforced disappearances

The concerted campaign in Bangladesh to undermine the UN’s work on enforced disappearances is ill-informed and entirely misplaced.

On October 7th 2022, India Today ran an article seeking to discredit a list sent to the Bangladesh government by the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID), which provided names of 76 men. The article, titled “'Travesty of justice’: Experts criticise errors in UN report on forced disappearances in Bangladesh” called the WGEID list as “replete with inaccuracies”, “shoddy”, and quoted the academic Imtiaz Ahmed as stating that it contained “fake cases”.

This article, which was widely reported in Bangladesh, has gone hand in hand with pro-government Bangladesh media and columnists seeking to question not only the veracity of the list (and hence the credibility of the whole WGEID process) but also the overall claims about enforced disappearances in Bangladesh and the United States' decision to impose sanctions on the Rapid Action Battalion and its current and retired senior officers.

India Today’s main criticism was that the leaked UN list includes names of people who it states should not be included. These are:

— at least 10 men “who are now staying with their families in Bangladesh”;

— the inclusion of the name of sacked military official Hasinur Rahman who it says “is now happily attending talk-shows online, advocating for the BNP”;

— two separatist insurgents, who are both back in India;

— at least 28 names of people who “have criminal charges against them”;

In making these criticisms, India Today along with those amplifying them, are however completely misunderstanding the purpose of the WGEID, how it works, as well as the nature of the list of 76 men which it sent to the Bangladesh government in 2021.

Since their key criticism is that the list contains names of people who should not be on it, their ire should be focused on the government of Bangladesh which is the key interlocutor with the WGEID, but which has consistently over the years failed to communicate with it.

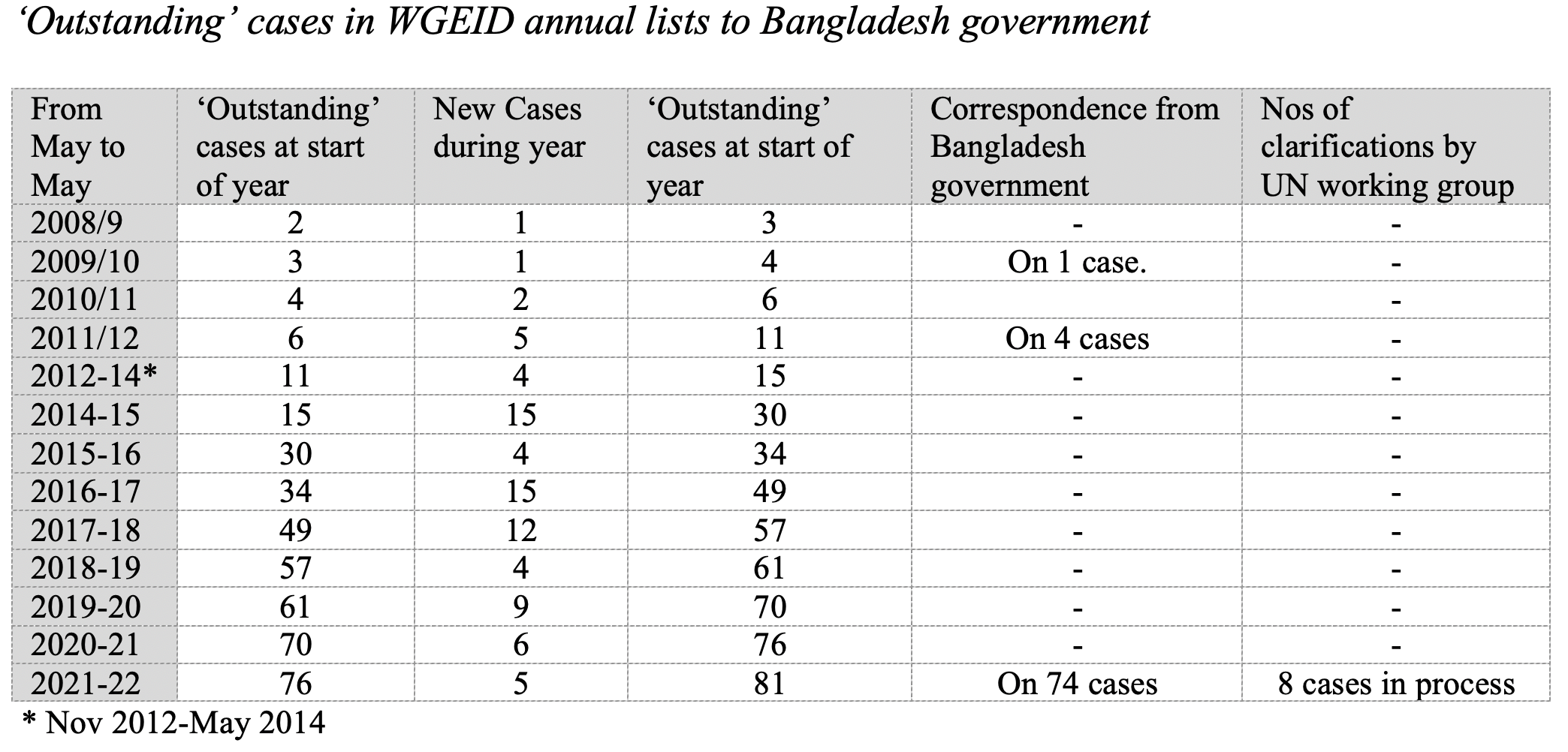

In 2019, the working group said that it "remains concerned about ... the lack of replies from the Government regarding its cases and communications." Two years later in 2021, the WGEID stated in its annual report that there has been “scarce engagement” by the Bangladesh government and that since 1996, the government has given adequate information on “only one case”. Although, since the Awami League came to power in 2009, the number of disappeared people on WGEID's list increased year on year, the Bangladesh government waited 12 years until 2022 before substantively responding to the working group - and even then the information provided was only sufficient to allow it to remove 8 out of the 76 from the list. And since then WGEID have received information on an additional 5 cases!

The lists of the disappeared

The critics' focus on the WGEID is a way of misdirecting people away from the actual number of men in Bangladesh who remain disappeared.

This is because, as the UN working group will happily admit itself, the number of people who remain disappeared in the country is not in any way reflected or fully captured by the figures contained in the lists it sends annually to the Bangladesh government. The working group is not a research or investigative body. It is a body whose primary function is “to assist families of disappeared persons to ascertain the fate and whereabouts of their disappeared relatives”. The only cases WGEID deals with are those where the families have contacted them directly and officially.

Far more significant in ascertaining the total numbers of those men who remain disappeared is the research undertaken, and the lists made, by both local and international human rights organisations, which — unlike the WGEID — is based upon detailed research and investigation.

First, there is the work done by Human Rights Watch (HRW) in Bangladesh which in August 2021 published a list detailing 86 men who were picked up by law enforcement bodies since 2010 and who remain disappeared. Prior to that, the organisation has done considerable work on documenting disappearances. This list is publicly available with information on each one of the men in English and Bengali which any one can check.

The HRW list is by no means a full list of those who remain disappeared. It only comprises cases where HRW was positively able to confirm with family members that the person, who was initially picked up, had not been subsequently released, arrested, or known to have been killed. "[HRW] only included names on the list where, at the time of publication, we could reach the family to confirm that the whereabouts of their disappeared family member remained unknown," Meenakshi Ganguly, HRW’s South Asia Director, told Netra News. There are likely to be other names who should be included.

Secondly, there is the list - also public - currently held by the Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) which is based on inquiries undertaken by local human rights defenders in Bangladesh. This is far more comprehensive than HRW's list and contains information about not only those who continue to remain disappeared (after having been picked up between 2010 and June 2022) but also those who were subsequently released, formally arrested, or known to have been killed. AHRC documents in detail 623 disappearances during this period, most of whom have now been released or formally arrested.

Out of the 623 names, AHRC says there are 153 people who continue to be disappeared. This is 67 more than the HRW list.

The UN working group

To understand the extent to which India Today’s criticism of the WGEID list is misinformed, one needs to understand both the purpose of the working group and the nature of the list of names it sends annually to the Bangladesh government.

The principal purpose of the UN working group is “to assist families of disappeared persons to ascertain the fate and whereabouts of their disappeared relatives," and in doing this, its principal interlocutors are first, the families of the disappeared, and secondly governments who have allegedly been responsible for the disappearances.

The working group only deals with a disappearance case when a family sends it a completed five-page official form answering questions concerning the identity of the disappeared person, how the person was picked up, what state agency picked the person up, and attempts by the family and others in trying to find that person.

The form needs to be filled out either by a relative or friend of the disappeared person or — with “the explicit consent of the family” — by a state, inter-governmental or civil society organisation. The working group does not accept information based solely on reports in newspapers or in human rights reports.

Any list compiled by WGEID is therefore not founded on information from any civil society group. If the UN list was based on AHRC’s information there would be 153 names on it. And if it was based on the HRW’s list, it would have 86 names. However, WGEID’s list sent to the government in 2021 only had 76 names on it. This lower number is because it relies on families providing it with information — not human rights groups. Many families for a variety of practical reasons do not send a form to the UN working group and so their cases are not included in any working group list.

On receiving information about an enforced disappearance, the WGEID sends the relevant government “all the available and relevant information received” about a case so that it can “carry out meaningful investigations.” The WGEID then awaits the government’s response.

A case will remain “outstanding” until the government or the family or other reliable source provides information to the WGEID about the fate of that person. When that happens it becomes a “clarified” case. As the WGEID puts it.

“Clarification occurs when the fate or whereabouts of disappeared persons are clearly established and detailed information is transmitted as a result of an investigation by the state, inquiries by non-governmental organizations, fact-finding missions by the Working Group or by human rights personnel from the United Nations or from any other international organization operating in the field, or by a search conducted by the family, irrespective of whether the person is alive or dead.” (emphasis added)

When the WGEID receives information from the government confirming that person’s whereabouts, it will give the family “six months” to respond. If the family “contests the state’s information on reasonable grounds, the state will be so informed and invited to comment.” When the family however does not contest the information from the government, the disappearance will become a “clarified case” and will be taken off the “outstanding” list.

Once a year, the working group reminds relevant governments about the cases that they have not yet “clarified”, by sending a list of “outstanding” cases

The Bangladesh government’s lack of response

Although the Bangladesh government has received regular correspondence from the WGEID about disappearance cases — first at the time it receives information about a case, and then annually about all the outstanding cases — the Bangladeshi authorities have rarely responded.

The WGEID annual reports since 2009 show that the Bangladesh government has only responded to it on three occasions - in 2010, 2012 and 2022, and when it has done so, the information provided does not allow the WGEID to remove names . In fact the only really substantive response from the government has been in January and February 2022 when the government sent information to WGEID on a total of 74 cases. This resulted in the WGEID starting the process of removal of 8 cases from the “outstanding” list. However, in relation to the other 66 cases, the UN working group concluded that “the information was considered insufficient to clarify them” (emphasis added). As a result they will remain on the list. Of course the Government was unable to provide details of the other 66 cases because they still remain disappeared.

India Today’s specific criticisms

“10 men now staying with families”

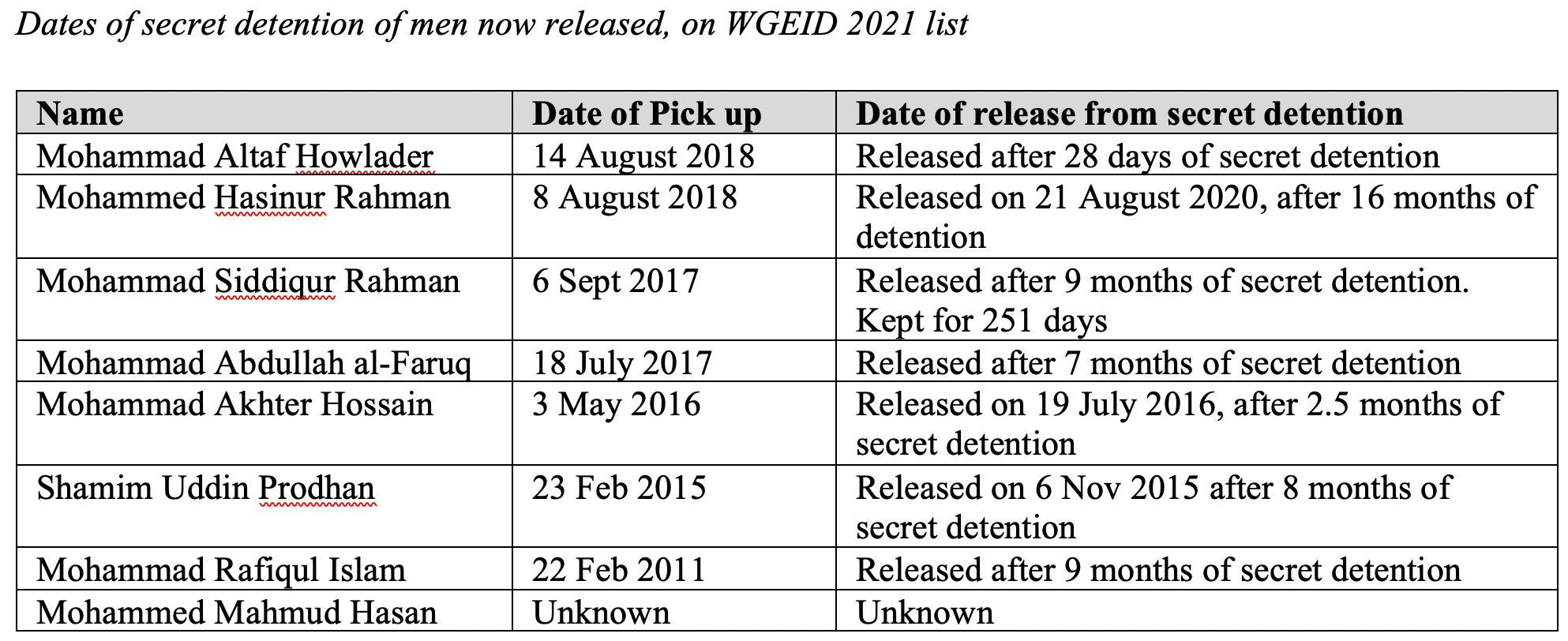

As mentioned above, the names of eight men are now in the process of being taken off the list, as in Jan/Feb 2022 the government provided sufficient information to WGEID about their present whereabouts. However, these men were released from secret detention years earlier: one in 2011; one in 2015; one in 2016; two in 2017; and two in 2018. Had the government informed the WGEID earlier, the names would have been removed earlier.

The India Today article seems to be suggesting that because the whereabouts of the men are now known, they were never picked up and disappeared. However, the AHRC database contains detailed information about how seven of the eight men were picked up, and provides information on when the authorities released them from their secret detention.

"Inclusion of Hasinur Rahman"

Hasinur Rahman was included on the WFEID list as he was picked up in August 2018 and disappeared for 16 months. The government released him in February 2020, at which point, it could have informed the WGEID of his whereabouts. Rahman remained on the “outstanding” list as the government’s failed for two years to do so. Below is a slightly edited version of how AHRC describes his pick up;

“On 8 August 2018 at around 10:20 pm, former commanding officer of RAB-7, Lt. Col. Hasinur Rahman was picked up by 10-15 plainclothes men from in front of the house of his sister-in-law at DOHS in Mirpur, Dhaka. His family said that three days before he was picked up some unknown persons had been roaming in front of his house. Hasinur had thought that he might be picked up and asked the security guard of his sister-in-law’s house, Moktar Hosain to take pictures. Just before Hasinur was picked up Moktar Hossain was able to take pictures of two white coloured microbuses waiting there. For this reason, Moktar was detained and put in a microbus. When Hasinur shouted, they picked him up in another microbus. Hearing their screams, people of that area approached the microbuses, then the men immediately put on jackets with "DB" written on the back (indicating they were from the police Detective Branch) and showed their weapons. After reaching a distance, they dropped Moktar blindfolded after taking his cell phone away. Later Hasinur’s relatives contacted the DB office but they denied that they had arrested Hasinur Rahman. On 9 August, Hasinur’s wife Shamima Akhter filed a General Diary with Pallabi Police Station.”

Hasinur was released on the night of 21 February 2020 after 16 months of secret detention. In August 2022, he gave an interview to Netra News confirming that he was kept detained in Aynaghor (House of Mirrors), a secret detention centre in Dhaka.

“Indian separatists on the list”

Interestingly, the original India Today article contained a lot of information about the presence of the two men on the list providing their names and the government of India’s narrative about what happened to them — but sometime after publication, the magazine removed this account. The article now only says that “two separatist insurgents, [are] both back in India,” without even naming their names.

The names of the Indians being referred to are Sanyama Rajkumar and Keithellakpam Nabachandra both of whom are connected to the militant United National Liberation Front (UNLF) which operated in the Indian North East.

The original India Today article sought to argue that the men were not disappeared in Bangladesh as they were both arrested at the Indian border whilst trying to enter the country. However, this is not what happened. In 2010, the WGEID annual report stated:

“Mr. Rajkumar Sanayaima … was allegedly abducted by a combined operation of the Indian intelligence agency, RAW (Research and Analysis Wing) and the Bangladesh intelligence agency from Lalmatia, area of Dhaka, under Mohammadpur Police Station, on 29 September 2010. In accordance with the Working Group’s usual practice, the Government of India received a copy of the case. The Government of Bangladesh acknowledged receipt of this case.”

In addition, the family’s concerns at the time were written about in an article on the BBC which also ran a report of Sanayaima’s claim to have been in secret detention in Bangladesh.

The alleged secret detention in 2015 of another UNLF leader, Keithellakpam Nabachandra, was also reported in the Indian media at the time

For over a period of 12 years in the case of Sanayaima, and 7 years in the case of Nabachandra, neither the Bangladesh nor the Indian governments informed the WGEID about the whereabouts of the two men.

“28 people with criminal charges”

India Today seems to be arguing two things about these cases.

First, since the men had criminal cases against them, they must have been absconding from court rather than being picked up and disappeared.

However, Netra News has seen the list of the 28 people who supposedly had criminal cases lodged against them. 18 of these 28 are on the HRW list of people who remain disappeared, with details of how state agencies picked them up. And all of them are on the AHRC list, again with details of how they were detained. Moreover, absconding from the country’s courts is not unusual and to do so people don’t need to get their families to pretend that they have been abducted by state agencies.

Secondly, the magazine seems to suggest that a person gets immunity from being picked up and disappeared if a criminal case has been filed against him. This is of course a preposterous position to hold.

And so …

The WGEID serves a very important function for families of the disappeared in Bangladesh - and in highlighting the overall problem of enforced disappearances. However, it is important not to lose sight that it is the lists produced by human rights organisations which are far more significant in terms of understanding the extent of disappearances in the country. It is this research - and not the WGEID list sent to the Bangladesh government - which inform the US government's position about Bangladesh's human rights record.

There are, at a minimum, 86 men, identified by HRW, who remain disappeared after having been picked up whilst the Awami League was in power. The government needs to provide explanations about what have happened to these men.

AHRC’s list contains an additional 67 names of men who may also still be disappeared. A job of human right defenders and journalists in Bangladesh right now is to clarify what is the situation with them. These 67 cases could mean that the number of people who remain disappeared under the current Awami League government may be as many as 150.●

David Bergman (@TheDavidBergman) — a journalist based in Britain — is Editor, English of Netra News. He also runs the bangladeshpolitico blog