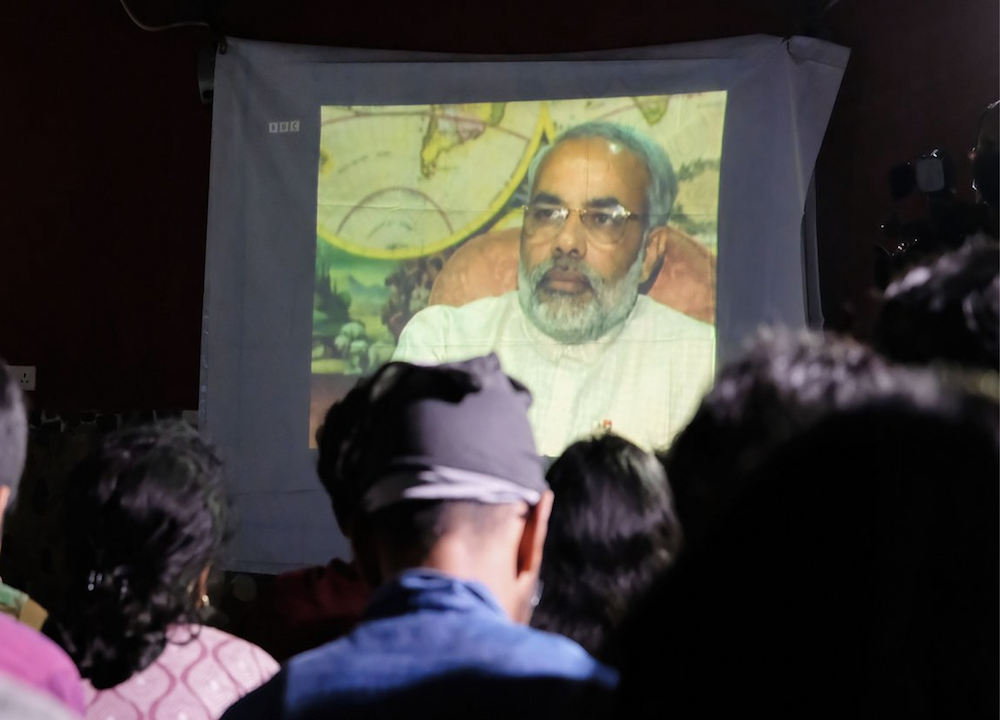

Proposed Bangladesh law lacks emergency powers used by Indian government to block BBC Modi film

As India orders YouTube and Twitter to remove all links to the BBC Modi film, Netra News looks at the powers the Bangladesh government has to remove from social media a film made by international broadcasters

Could the Bangladesh government order social media companies to remove all links to a film made by an international broadcaster on the basis that its distribution in the country would result in an emergency?

This is exactly what the Indian government has done in relation to the BBC documentary series “India: The Modi Question” which in two programmes investigated Modi’s complicity in the 2002 Gujarat riots. On January 20th, the Indian government instructed Twitter and YouTube to remove all links to the BBC documentaries. The social media companies complied.

The Indian government used its legal powers set out in rules framed in 2021 by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology pursuant to powers contained in the Information and Technology Act. Rule 16, titled “Blocking of information in case of emergency,” states:

(1) Notwithstanding anything contained in rules 14 and 15, the Authorised Officer, in any case of emergency nature, for which no delay is acceptable, shall examine the relevant content and consider whether it is within the grounds referred to in sub-section (1) of section 69A of the Act and it is necessary or expedient and justifiable to block such information or part thereof and submit a specific recommendation in writing to the Secretary, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

(2) In case of emergency nature, the Secretary, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting may, if he is satisfied that it is necessary or expedient and justifiable for blocking for public access of any information or part thereof through any computer resource and after recording reasons in writing, as an interim measure issue such directions as he may consider necessary to such identified or identifiable persons, publishers or intermediary in control of such computer resource hosting such information or part thereof without giving him an opportunity of hearing.

Lawyers in India are now challenging the government decision claiming it to be “mala fide, arbitrary and unconstitutional.”

In the context of Bangladesh, the most obvious recent comparison to the Modi film is the Al Jazeera documentary “All the Prime Minister’s Men”, broadcast in February 2021, which exposed corruption at the heart of the Bangladesh state in particular involving the then chief of army staff, General Aziz Ahmed.

Watched by millions of people in Bangladesh on YouTube — the English language version of the film has been seen by 8.5 million viewers, and the Bengali version by 6.5 million — the Bangladesh military authorities called it “concocted”, and made by a “vested group which has been attempting to destabilize the country” and to “obstruct [...] the growth and development of the country.”

After social media companies did not respond positively to informal entreaties by the Bangladesh government to remove the Al Jazeera film from their platforms, private lawyers petitioned the Bangladesh High Court in a “public interest” writ arguing that the the documentary constitutes “nothing but a hostile attempt to destabilise the secular government of Bangladesh and undermine the image at a global level”.

In its ruling in March 2021, the court appeared to accept the petitioner’s criticism of the documentary, though without providing any explanation why, stating that:

“We as the sons of this soil are equally shocked and feel humiliated when we find that the honour, dignity, and prestige of out head of the State, Government and that of the Army Chief are being maligned, tarnished, demeaned by none other than through an international T.V channel and some social medias.”

The judges however ruled that Bangladesh had no laws to order social media companies to:

“take down any content that may malign the prestige and dignity of the highest authorities of an elected democratic government or to stir public sentiment of a particular country.”

Since then, in early 2022, the Bangladesh Telecommunications and Regulatory Commission (BTRC) drafted a new regulation which seeks to significantly increase government powers to order the removal of social media content which is available to those accessing content from Bangladesh. This regulation was drafted in response to a High Court order (relating to a different case) which ruled that the government should draft a law regulating social media and other similar websites.

In the first draft published in order to seek comments, the proposed regulation did contain a very similar “emergency” provision as the one set out in Indian law. This stated:

Blocking of Information in case of Emergency

11.01 Notwithstanding anything contained in this Regulation, the Authorised officer of BTRC, in any case of emergency nature, for which no delay in acceptable shall examine the relevant content and consider whether it is within the grounds referred to in Article 141 of the Constitution of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh and it is necessary or expedient and justifiable to block such information or part thereof and submit a specific recommendation in writing to under section 8 of the Digital Security Act, 2018

11.02 In case of emergency nature, the Director General of Digital Security Agency may, if he is satisfied that it is necessary and justifiable for blocking public access of any information or part thereof through any computer resource and after recording reasons in writing, as an interim measure issue such directions as he may consider necessary to such identified or identifiable persons, publishers or intermediary in control of such computer resource hosting such information or part thereof without giving him an opportunity of hearing.

Although, the proposed Bangladesh section was an almost identical provision of the Indian law, there was a substantive difference concerning the meaning each of the country's legal provisions (or proposed legal provisions) gives to the term “emergency”.

The Indian law refers to Section 69A of the IT act, which in effect defines “emergency”, for this purpose, as being when it:

“is necessary or expedient to do in the interest of the sovereignty or integrity of India, defence of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognizable offence relating to above or for investigation of any offence...”

This is quite a broad definition of emergency - including in the interest of "public order". The proposed Bangladesh law however refers to Article 141A of the constitution which defines emergency more narrowly as being where:

“the security or economic life of Bangladesh, or any part thereof, is threatened by war or external aggression or internal disturbance…”

The meaning of “emergency” in the Bangladeshi constitutional provision is significantly narrower than the one contained in the Indian law, and therefore, if applied properly, could only be used in a much more restricted set of circumstances.

In the final BTRC draft, submitted to the court, these sections were, however, absent.

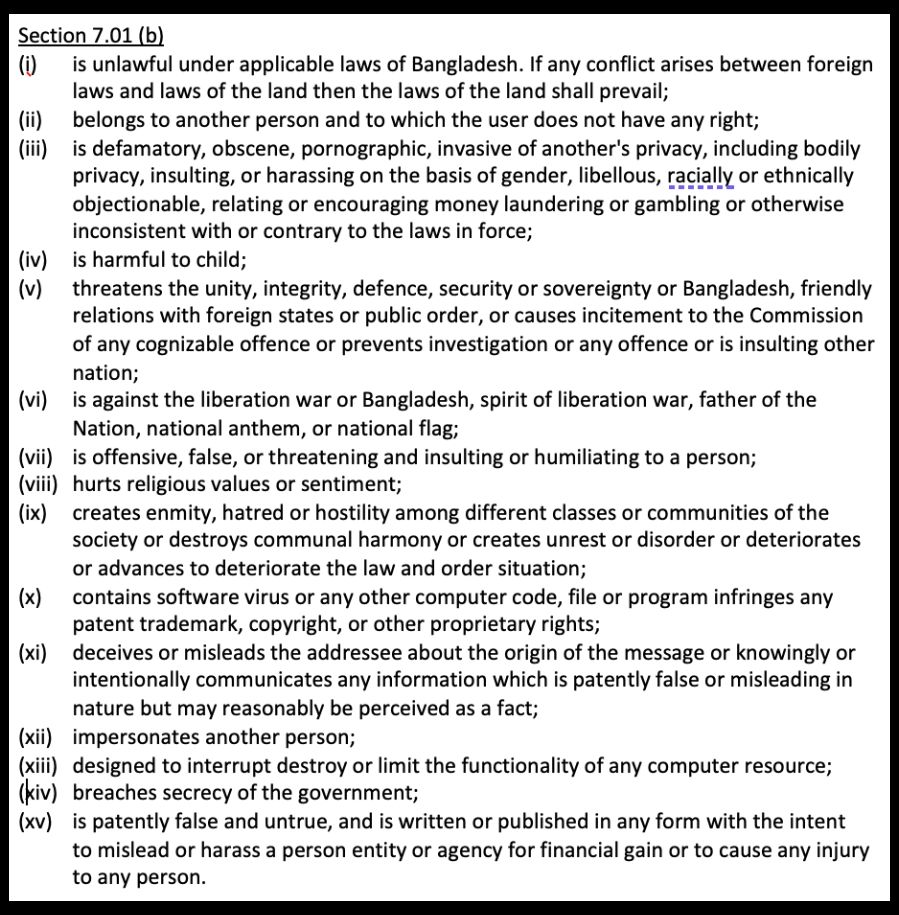

This though does not mean that, were this regulation to be framed in this form, the Bangladesh government would not have the power to order removal of the links to any critical film in the future — as the final draft of the regulations retains others powers available to the government to seek removal of content, without having to claim that there is an “emergency” requirement.

The table above sets out the kinds of content which the final regulation states that social media in Bangladesh should not contain and which the government can order to be removed.●