Why parents filed no complaints for killing of fifth grader

The aftereffect of the tragic death of an 11-year-old at home by an apparent police shooting exposes the political and cultural sensitivities of a nation under authoritarian rule

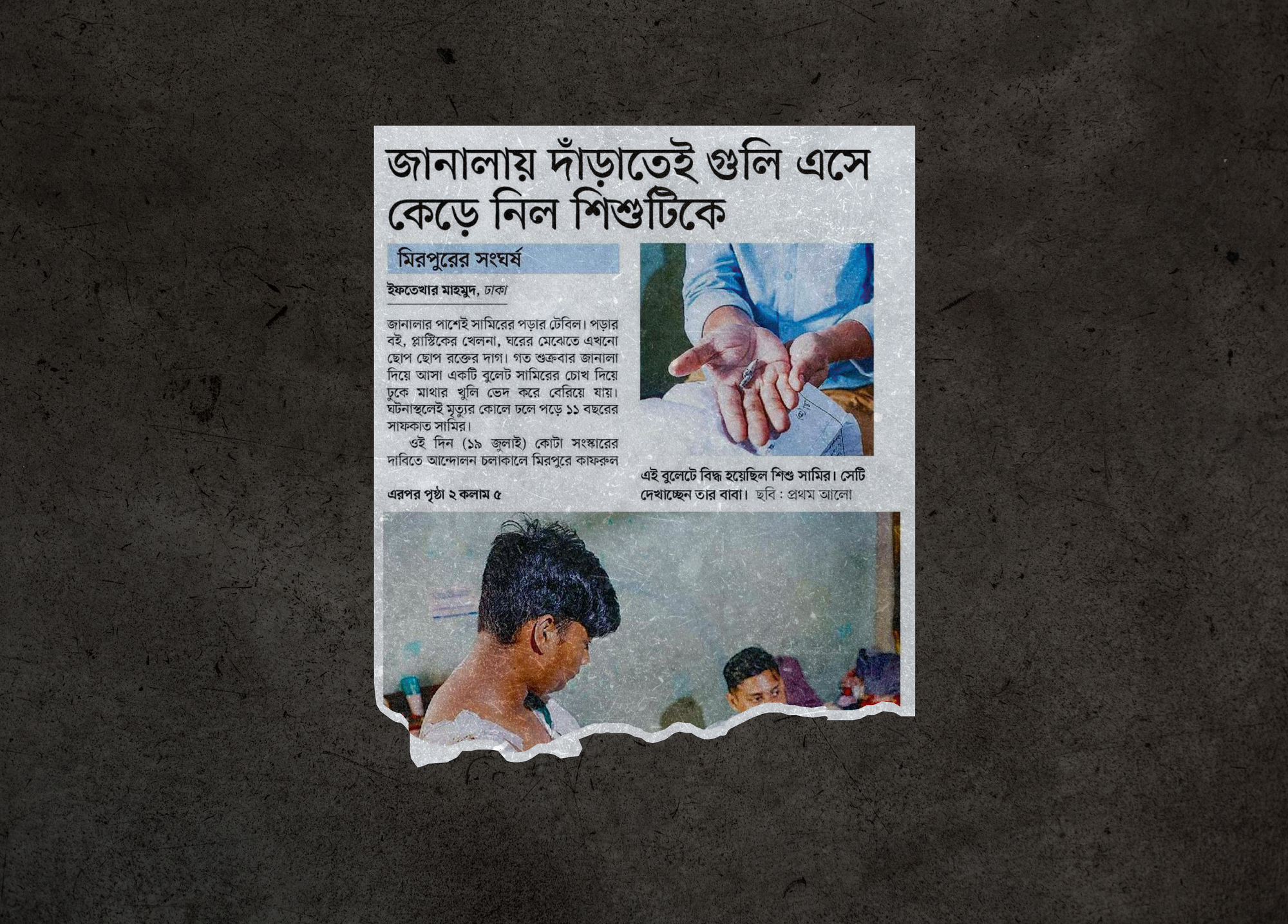

When an 11-year-old school child was allegedly killed by police for looking out the window during recent civil unrest in Dhaka, his parents declined to press charges, according to a report in Prothom Alo, a leading local daily.

It’s unclear precisely under what circumstances the child was killed, but the episode highlights the cultural and political sensitivity in a country like Bangladesh when it comes to seeking accountability for acts of injustice.

Safqat Samir, a fifth-grade student who was killed on July 19, was not among the many student protesters engaged in fierce street agitations against heavily armed police, paramilitary, and military units. Instead, his family were strong supporters of the ruling Awami League party and complying with stay-at-home orders.

Samir wasn’t even outdoors playing. He was inside his home in the Mirpur neighbourhood of Dhaka. When he looked out the window before trying to close it to prevent tear gas from entering, a bullet hit his skull through his eye, killing him almost instantly, according his father.

“We have not undertaken any anti-government activities. We have followed whatever the government has said. Since the curfew was declared, we kept the entire family at home. If we can’t even be safe in our own home, where are we to go?” Sakibur Rahman, the father, told Prothom Alo.

“I support the Awami League. Our entire family and the majority of the people in this neighbourhood support the Awami League. We voted for the Awami League at the last election. There is no one here who would create any problems for the government. Why would this happen to us? Why shoot at our home? What sort of rule is this?”

Samir wasn’t likely hit by a stray bullet. His uncle, Moshiur Rahman, 17, who was with him at the time, took a bullet to his shoulder, too. Someone likely targeted them.

Sakibur said he rushed home on that fateful day because a helicopter was raining down gunfire and sound grenades from the sky. When he reached home, he found his son lying on the floor in a pool of blood.

When a doctor at a nearby hospital declared his son dead, Sakibur was faced with two options: press charges for manslaughter — an effort that never guarantees accountability and could even backfire on him — and go through a long, arduous and expensive bureaucratic process; or conduct a proper, quick funeral and burial, which in Bangladeshi Muslim culture is often warranted in the interest of emotional and societal closure.

Sakibur chose the latter.

“The officers at the police station presented me with a written form. They said, ‘Sign here. Otherwise, you will get into trouble. Investigation, interrogation, evidence presentation. People will play politics with the corpse of your son,’” Sakibur said.

“I have no complaints regarding this matter. I do not want to file a case. I wish to take my son’s body and bury him,” the document he signed reads.

“When a typed form with these words was placed in front of me, I only considered a few thoughts: I lost my son, he suffered in pain before he died, nothing can be worse than not giving him a proper, timely burial. Thinking this, I signed the form,” he added.

Earlier, young people and neighbours had gathered outside the hospital as doctors formally pronounced the child dead.

They wanted to march with the body in protest, to demand justice, Prothom Alo reported.

But inside the hospital, Ismail Hossain, a distant relative of the victim’s family and an influential member of the Dhaka Awami League, reminded Sakibur that the father’s responsibility was to avoid legal wranglings and bury the child’s body with dignity.