If this is a new beginning, what about the Chittagong Hill Tracts?

The events culminating in Hasina’s fall serve as a reminder of the methods of disenfranchising the Indigenous Peoples. Their systemic exclusion cannot continue if Bangladesh is to fulfil the promise of this victory.

When the former Prime Minister of Bangladesh Sheikh Hasina lashed out at student protestors on July 17th by calling them ‘razakars’ she never fathomed that she had triggered a chain reaction that would lead to the very humiliating downfall of herself and her Awami League party. Over the previous 15 years, she and her party had carefully crafted her legitimacy by weaponising the 1971 War of Independence and by violently suppressing all forms of opposition and criticism of her government.

Sheikh Mujib’s role in bringing independence to the country and the tragic killing of her entire family in 1975 became the crux of her political capital, and she never missed the opportunity to repeatedly remind the public that the country owed their independence to her, her family, and her whole repertoire of ministers and MPs. Anyone who stood in the way of the Awami League were enemies of the state, enemies of the spirit of Liberation, and thus ‘razakars’.

When hardworking university students, in their teens and twenties took to the streets to demand that the corrupt and nepotism-ridden freedom fighters’ quota be scrapped so that the general population of the country had a chance to compete for government jobs, she drew out her ‘razakar’ card once again. The Gen Z of Bangladesh who were born decades after the 1971 war and had nothing to do with the ‘razakar’ politics of 1971, were not going to give her this opportunity to gaslight them into submission. Intending to taint and criminalise the protestors by calling them ‘razakars’, Hasina instead triggered the most widely participated demonstrations in the history of the country and ended up becoming the only prime minister to be forced to flee into exile after resigning from the highest position of office.

Sheikh Hasina, in her arrogance and overconfidence made a crucial mistake. Instead of engaging meaningfully and democratically with the citizens of the country, dismissed the students as ‘razakars’. By mobilising nationalist sentiment, the intended effect of casting this aspersion is to vilify a group of people. It has been done before and has achieved its intended effects.

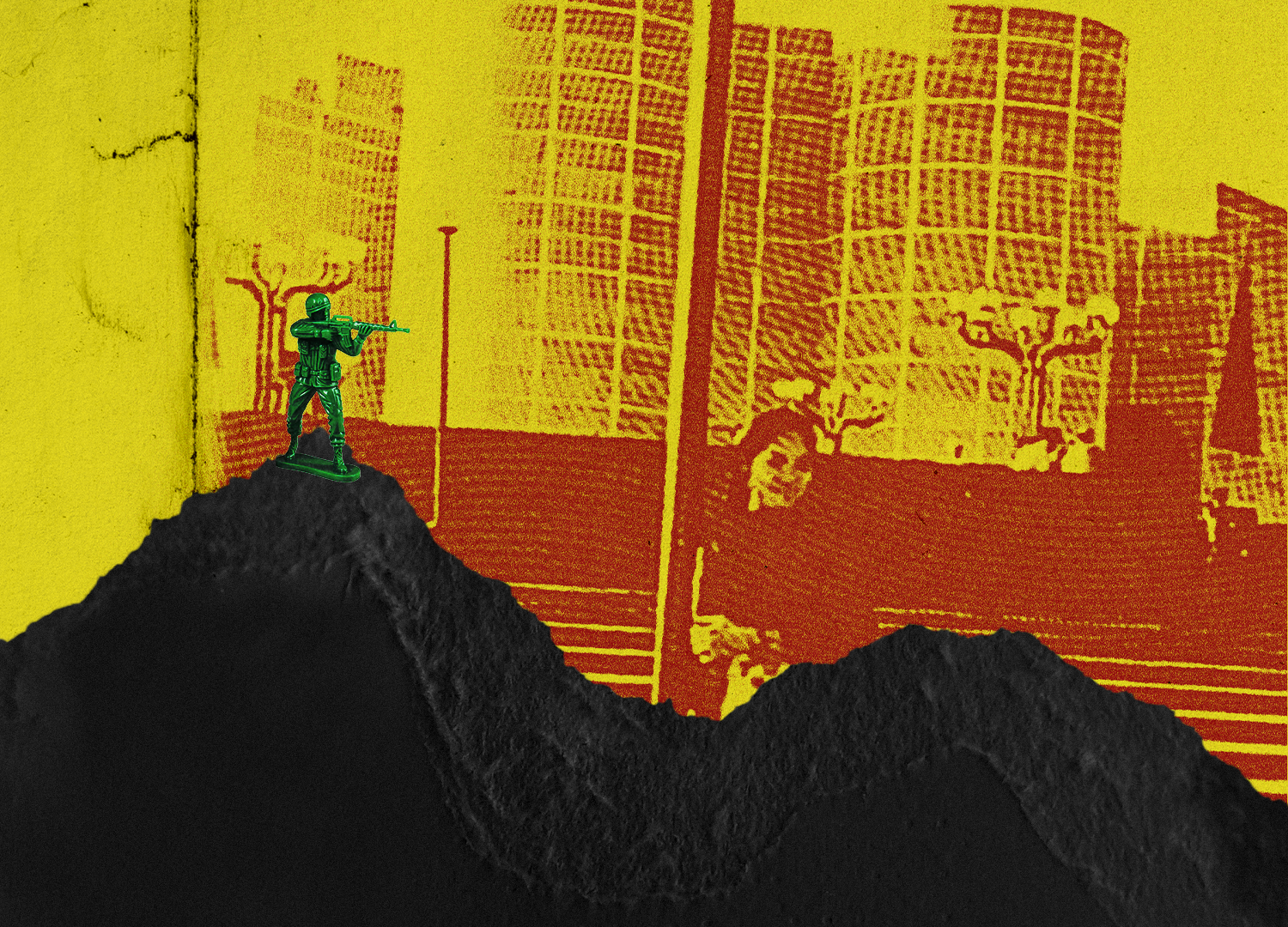

Since the birth of the country, mobilising nationalist sentiment has helped to sustain the political instability in the Chittagong Hill Tracts region by othering Jummas of the country. While the rest of the country had been enjoying some form of democracy, this region has been living under military occupation in a supposedly independent country. Therefore, while the country turned into a war zone in what has been termed ‘Bloody July’, the Jumma activists from the Hill Tracts began to see similar patterns of violence and repression that they have been experiencing for more than four decades.

Muktasree Chakma, an Indigenous feminist activist, in a Facebook post exclaimed, “The entire country has now become the Chittagong Hill Tracts, for the last 52 years this has been carried out upon the Adibashis of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and many of you have been giving validity to these acts in the name of nationalism.” Making of hit lists, mass arrests and false cases, declaring curfews, threatening the friends and families of activists and refusal of the police to file cases against attackers are all common tactics in the playbook of repression carried out by the military in the Hill Tracts. These tactics have remained in force in the region since the independence of the country. The demands for recognition of the Adibashis in the constitution is yet to be met.

Ananta Dhamai, an activist for the Parbatya Chattagran Jana Sanghati Samily (PCJSS) which signed the CHT ‘Peace’ Accord in 1997 with the then Sheikh Hasina government, posted a photo of military officers checking the grocery bags of ordinary women on the streets. It is not clear what they were looking for, but the expected performative effect of this act is clear. Ordinary civilians under extraordinary circumstances are always suspicious and need to be reminded that they are under surveillance.

Under the extraordinary circumstances of late-July, checking the bags of ordinary, working women of Dhaka became part of the surveillance system of the state. But Ananta reminds us that such surveillance takes place under ordinary extraordinary circumstances in the hill tracts. “The residents of the Hill Tracts have been living under curfew for the last 50 years,” he says in a Facebook post, “and the people in Dhaka and other districts are tired of the curfew in only 12 days, just imagine!”

Samari Chakma, a lawyer, former Hill Women’s Federation President, and author of Kaptai Badh: Bor Porong, an oral history collection of people who were evicted by the construction of the Kaptai Dam adds, “The killer state. For so many decades it has been eating the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Now they are eating the country’s students and the general population.” For Jummas who have grown up in the region and experiencing military control, surveillance and arbitrary arrests and other forms of human rights violations by the state security agencies has been normalised.

The frequent movement of olive-colored jeeps along with the uniformed army personnel on the street is an everyday phenomenon. Those uniformed army personnel are a constant reminder for those who have lost their family members through direct atrocities by the state security agencies of the fact that they have to continue to live with the perpetrators of violence upon them. The tools of control do not end there. While the students across the country erupted in anger at the disparagement intended by the Prime Minister with the use of the term ‘razakar’, Jummas are constantly disparaged with terms such as ‘razakar’, ‘terrorist’ and ‘anti-state’.

Many Indigenous Peoples actively participated in the liberation war of Bangladesh in 1971. However, a widely popularised discourse in Bangladesh is that they did not support the formation of Bangladesh. Thus, Jummas are constantly put into a situation where they have to prove their patriotism by constantly reminding everyone about the contributions they made during that time. When disparaging labels are thrown at them questioning this patriotism, there are no protests. This labelling continued during the student movement by maligning and mocking of Indigenous People as nonchalant or inactive on social media during the anti-discriminatory movement. A widely circulated post profiling people who hadn’t participated in the student movement exclaimed, era noreo na choreo na (they are barely moving around).

Activists from the mainstream communities are often quite clueless of their own privilege. While many Jumma activists actively participated in the student movement, it seemed that every single Jumma person needed to turn their profile red on Facebook in order to be accepted into the movement. At the same time, the exclusionary chants of Ami ke tumi ke, Bangali Bangali, (Who are you? Who am I? Bengali! Bengali) went around quite a bit and it wasn’t until much later that the alienation caused by this chant was pointed out by Indigenous communities. The sentiment here invisibilises the fact that there has been very little support from the wider Bengali community over the human rights violations in the Hill Tracts for the last 50 years.

It also invisibilises the fact that the cancellation of the quota meant as a form of affirmative action for historically marginalised Indigenous communities, was ignored by the larger movement. Such labelling denies and ignores the historical oppression on Indigenous people by the Bangladeshi state. Many Bengalis in social media platforms use disparaging terms such as khudro nri goshthi (small ethnic groups) and upojati (sub-national) without any regard for how disparaging this appears. It doesn’t bode well if a student movement that claims to fight against discrimination focuses on one form of discrimination and fails to acknowledge the other forms of discrimination that exist in our society.

This disregard and disparagement of Indigenous Peoples is a form of ongoing colonial, gendered and racial state violence. The Indigenous people in the CHT and the plains have been racialised, profiled and oppressed whenever the state felt the necessity to control their resistance, mobilisation and movements for justice, and voicing against the repression. One of the manifestations of such authoritarian state violence tools is filing cases against Indigenous activities and Indigenous people by framing them as criminals. For instance, in recent months the whole Bawm community has faced profiling, violence, arbitrary arrests when they were labelled as ‘terrorists’ following the activities of the Kuki Chin National Front (KNF). There was very little national awareness or sympathy towards the Bawm community from the rest of the country. These poor Bawm families continue to be incarcerated in Bandarban jails without any evidence against them.

Before being abducted by the military in June 1996, Kalpana Chakma said one time, “Whatever is being experimented in the hills, will also be implemented in the plain lands”. During the recent anti-discriminatory movement, many Indigenous activists pointed out that the issues of the Indigenous communities have always been sidelined in the national agenda. Even when the movement was focused only on the quota, it was shocking to see that the quotas that were meant as affirmative action for marginalised communities, were also scrapped in 2018. Jumma activists had been trying to reinstate the quotas for the last six years, and had made no progress. There has been very little support from mainstream communities during these efforts.

In addition to that, while the student movement has done an admirable job to challenge state authority, the military occupation in the Hill Tracts has always remained a non-issue in the national agenda. Satej Chakma, a student leader from Dhaka University and the editor of the Shonghoti magazine thus expressed his scepticism of whether this movement will mean anything for the situation of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. “Je lau shei kodu” (lau and kodu are different names for the same vegetable), he said, meaning that none of the national democratic uprisings have brought about any changes to the practices in the region – it has remained under military occupation for the last 50 years.

August 5th is being celebrated by many as the “Second Victory Day” of Bangladesh. For the last 16 years, the Awami League party and their affiliates have been carrying out unrestrained corruption, censorship and a brutal repression of all forms of dissent and opposition. Although the movement started as a quota reform movement, it gained momentum and wider participation when it morphed into an anti-discrimination movement. In the coming days the interim government must ensure not only that a free and fair election is held under them but also that the corrupt system is dismantled from the very core, that the constitution goes back to its secular and democratic values and that a civilian administration is in place in all 64 districts of the country. This is the time to also make the Chittagong Hill Tracts a part of this “victory”.●

Hana Shams Ahmed is the former coordinator of the International Chittagong Hill Tracts Commission and is currently a PhD candidate at York University, Toronto, Canada.

Parboti Roy is a lecturer (on study leave) at North South University and currently a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.