Why do anti-India sentiments simmer across Bangladesh?

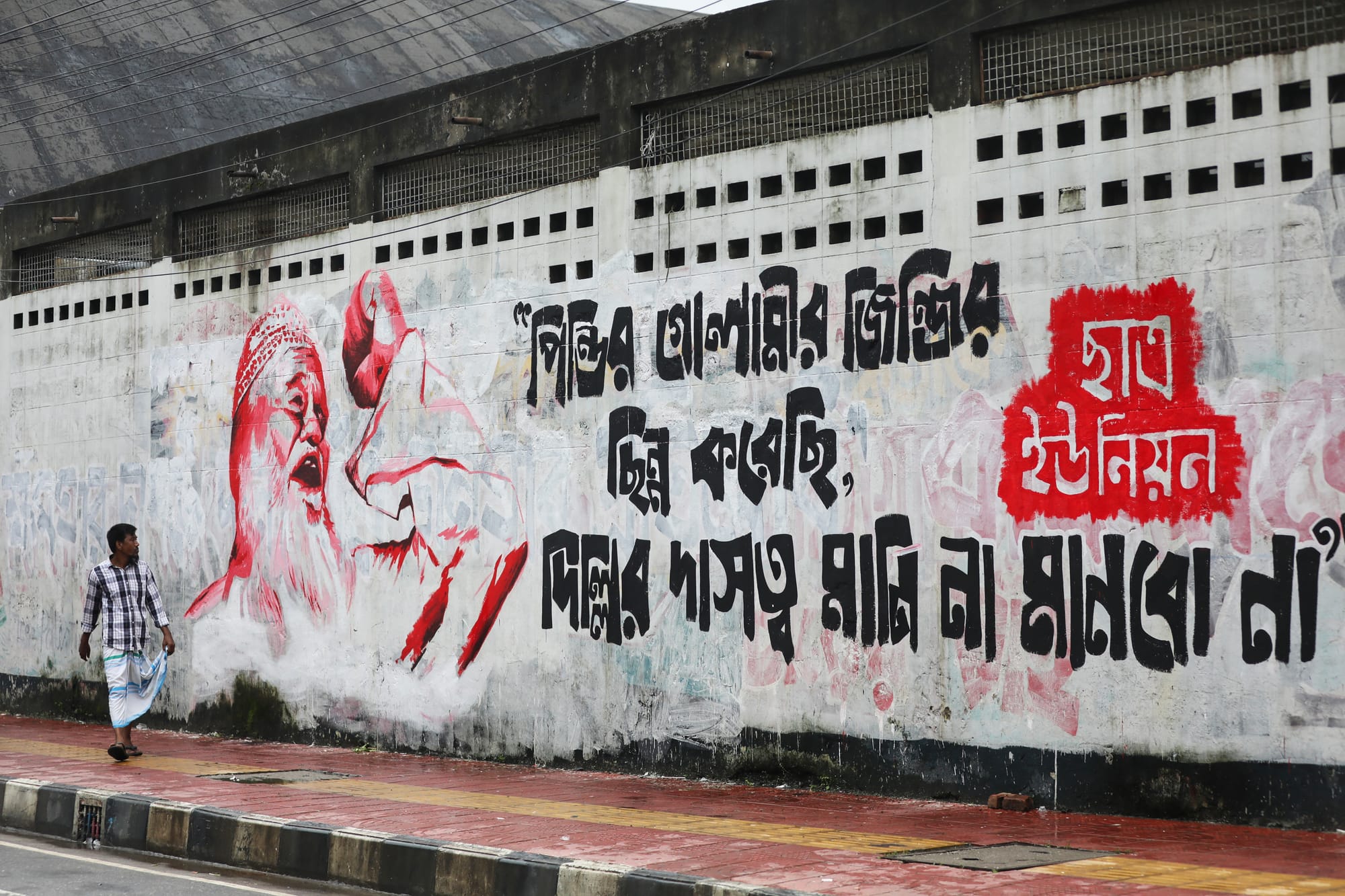

Decades of mistrust, rooted in historical grievances, economic disparities, and political interference, have fueled deep anti-India sentiments in Bangladesh. The ousting of Sheikh Hasina following a student-led uprising has brought these tensions to a boiling point.

For Rezwan Rahman Sadid, a final-year medical student at Rajshahi Medical College, anti-India sentiment in Bangladesh is not new, but it has taken on a sharper, more pervasive edge in recent years.

“The current hatred or inability to see India positively stems from Indian hegemony, their dismissive attitude towards Bangladesh, and the propaganda they perpetuate about us,” he said. To him, the tensions have boiled over in recent years, exacerbated by events that highlight what he perceives as “India’s condescension towards its smaller neighbour.”

A cricket enthusiast, Sadid recalled an incident from 2015 that struck a nerve with him and many other Bangladeshi cricket fans. “Do you remember the Indian media’s promo during the 2015 series? They mocked us, saying ‘Bacche ab bacche nahi rahe.’ (The children have grown up.) For a cricket-loving nation like ours, it was deeply humiliating. These provocations are enough to cause bitterness,” he said.

His frustration goes beyond sporting slurs. Sadid pointed to systemic issues that have long strained the relationship between the two nations. “Our markets are flooded with Indian goods, but our products barely make it to theirs,” he argued. “We have known about these imbalances for years, but after Sheikh Hasina’s fall, the extent of India’s influence and exploitation is all coming out in the open.”

Hasina’s 15 and a half-year rule ended dramatically in August 2024, with a student-led uprising toppling her government. Brutal state crackdown on the protests caused over 1,000 casualties. In the aftermath, government buildings were ransacked and Awami League activists were persecuted. Hasina fled to India on August 5th, where she has resided since under the protection of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi – a development that has only deepened anti-India sentiment.

For many Bangladeshis, Hasina’s safe refuge in India and resulting impunity symbolise New Delhi’s insuperable entanglement in Bangladesh’s domestic politics. “India’s support for Hasina, even after all the corruption and misgovernance, shows how little they care about Bangladesh’s sovereignty,” Sadid said.

Nationwide protests erupted in response, with chants of “India Out” echoing across the capital and other cities. The frustration was not confined to Bangladesh. In Agartala, Tripura, the Assistant High Commission of Bangladesh was attacked by Hindu nationalist protesters with links to India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). They claimed their actions were in retaliation for perceived violence against Hindus in Bangladesh after Hasina’s fall.

Mutual hostility has been amplified by Indian media according to Amena Mohsin, a professor of International Relations at the University of Dhaka. “The disinformation campaigns we see today are deliberate. They create a narrative of Bangladesh as a failing state without Hasina, but these are harmful and do not reflect reality. It only deepens the mistrust on both sides,” she said, noting that there is no way to deny attacks on minority communities, which needed to be addressed.

Sreeradha Datta, a professor at the Jindal School of International Affairs in Sonipat, Haryana, agreed that the media has played a significant role in shaping perceptions. “It’s difficult for the average person on either side of the border to differentiate between fact and propaganda. This deepens hostility and mistrust,” she observed.

Unresolved issues that have long plagued the bilateral relationship are adding to the mistrust. Economic inequality, trade imbalance, and contentious agreements have only fanned the flames.

Sadid was critical of the economic dynamics, particularly agreements he felt benefited India disproportionately. “Crucial issues like the fair share of river water, border killings, and unresolved disputes have been sidelined. Instead, concessions were given, such as transit facilities and access to ports, without ensuring reciprocal benefits for Bangladesh,” he argued.

Tabassum Oishy, a student at Independent University Bangladesh, believes her generation feels a sense of disenfranchisement, having been unable to vote in any election since coming of age. “When you grow up without the ability to exercise your basic democratic rights, and then you see India being accused of meddling in those elections, you naturally feel a sense of animosity,” she said.

Mohsin concurred, placing the frustration of the nation’s youth within the broader context of political reliance. “A whole generation has grown up without being able to cast a vote or exercise their right to franchise, and India had a direct role to play in validating or manipulating those elections,” she said.

“This has fostered a sense of hatred for India among our youth,” she added. "Our political parties, particularly the Awami League, have relied more on support from India than from their own people, and the visible involvement of the Indian establishment in Bangladesh’s domestic affairs has only deepened this divide.”

“When political changes occur in India, we observe, follow, but do not interfere. However, that is not the case with India’s involvement in Bangladesh’s politics,” Mohsin said.

India has publicly shown increasing concern over Bangladesh’s Hindu population since the end of the Hasina regime. Mohammad Tanzimuddin Khan, a professor of International Relations at the University of Dhaka, described the use of the “religion card” as a “cycle of complementary hatred” that benefits political groups on both sides. “This mutual reinforcement of hatred has become a deeply embedded social phenomenon,” he said.

The rise of the BJP and its brand of Hindu nationalist politics in India, he argued, has further fueled a reciprocal rise in anti-India and anti-Hindu rhetoric in Bangladesh. “The BJP’s anti-Muslim stance made it easier for religious fanatics in Bangladesh to rally against India, to some extent cultivate animosity towards the Hindu community, and the situation is vice versa across the border.”

Datta, echoed this, noting how the rise of religious politics on both sides has created a dangerous cycle of mutual hatred. “On our side, there’s a Hindu-majority perspective, while in Bangladesh, there’s a Muslim-majority dynamic. These differences add layers of complexity to the relationship,” she said.

“The BJP’s strategy of portraying Bangladesh as a potential ‘terrorist state’ underpins its justification for supporting Hasina,” she added. “By doing so, it positions itself as a protector against extremism, while also reinforcing anti-Muslim narratives in India.”

Khan stated that this approach has further strained relations between India and Bangladesh. “The Indian establishment’s overt reliance on Hasina and its unwillingness to envision a Bangladesh without her, have alienated large segments of the Bangladeshi population,” he said. According to him, this framing has contributed to growing mistrust and resentment among Bangladeshis.

Datta rejected the notion that India sought to portray Bangladesh or other Muslim-majority nations as a “terrorist state”. Instead, she attributed India’s support for Hasina to its longstanding ties with the Awami League.

“India has been working with the Awami League for so many years – this is not today’s Awami League, but the one from the time of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman,” Datta said. “Whether it’s Congress, the BJP or any other party in Delhi, India has consistently found it easier to work with the Awami League compared to what we saw during the Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s (BNP) last rule from 2001 to 2006."

Datta highlighted security concerns as a key factor in shaping Indian attitude. “During 2001–2006, the frequency of terror attacks was significantly higher. If you look at the trend, such incidents seem to decrease when the Awami League is in power,” she noted. “Even now, after Hasina’s fall, the emergence of outfits like Hizb ut-Tahrir and many other fundamentalist-run provocative rallies have reinforced the perception among many Indians that the Awami League provides greater stability in this regard.”

When asked if the Indian government or a faction within it cannot accept a Bangladesh shorn of Hasina, Datta said, “That seems to be the case as I see.” She added, “I’ve repeatedly said that while India has had reasons to work with the Awami League, they certainly won’t stop working with other governments. India must establish a new rhythm with whoever comes next.”

“Having worked with the same party for 15 years, if that breaks, naturally, a challenging situation arises because India in the past decade didn’t keep any relations with any other political party," she explained.

Khan argued that the transactional nature of the Modi-Hasina relationship has only exacerbated this cycle. “The relationship between the two countries has increasingly become one of transactional politics, moving away from state-to-state dynamics to more personalised diplomacy,” he said. “For much of the past 15 to 16 years, the Hasina government prioritised satisfying India’s demands, more specifically the BJP or Modi’s demands, over safeguarding Bangladesh’s national interests.”

Khan pointed to specific examples of this imbalance, including the agreements with Adani in the energy sector, and concessions on transit and port access, as emblematic of Bangladesh’s diminished bargaining power. "These agreements reflect how personalised relations between leaders have overridden state-level negotiations. The reliance of the Hasina government on Indian support for political legitimacy has fundamentally altered the nature of this relationship,” he said.

For many Bangladeshis, these grievances are compounded by memories of India’s role in the Liberation War and its aftermath. Khan traced the roots of anti-India sentiment to 1971, when India’s support for the Awami League created divisions among freedom fighters. “The formation and patronage of the Mujib Bahini by India created mistrust among many general freedom fighters, who felt sidelined during the war,” he said.

Khan highlighted symbolic moments that reinforced Indian dominance, such as the surrender of Pakistan’s combined forces to Indian General Jagjit Singh Aurora instead of Bangladesh’s General M. A. G. Osmani. “This was seen as an assertion of Indian superiority and alienated segments of Bangladeshi society,” he said.

These grievances, while rooted in the past, continue to influence perceptions of India’s role in Bangladesh. Khan explained how these narratives have been institutionalised over the years, particularly through the Awami League’s close ties with New Delhi. “The role of the Awami League in formalising this dominance further alienated those segments," he said.

After Hasina’s fall, anti-India rhetoric has become more mainstream, with nationwide protests and calls for reduced Indian influence.

Social media has amplified these sentiments, turning grievances into mass movements. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter have become arenas for divisive narratives, with both sides using them to stoke animosity. “The proliferation of social media and the politics of populism have significantly amplified India-hatred in Bangladesh and vice versa,” Khan said. “Platforms have been used to propagate extremist narratives, often monetising hate for views and engagement.”

The interim government led by Muhammad Yunus has attempted to counter these narratives, dismissing allegations of anti-Hindu violence during the unrest as part of an “industrial-level disinformation campaign.” However, the damage has already been done, with many Bangladeshis viewing India as an overbearing, manipulative neighbour.

For Datta, rebuilding trust between the two nations requires a fundamental shift in approach. “Building a new rhythm with the transitional government in power and whoever comes next is essential,” she said. Datta emphasised the importance of addressing grievances by state actors on both sides of the border, to prevent further deterioration of relations. “Both countries share a long border, 54 rivers, and countless cultural and economic ties. Our mutual needs must take precedence over political differences,” she added.

Khan warned that the current trajectory is unsustainable and risks destabilising the entire region. “The hatred between the two countries is no longer limited to political disagreements. It is now rooted in religious identity, creating a dangerous feedback loop,” he said. “If this continues, it will destabilise the entire region, as the animosity between their populations grows deeper and more entrenched.”

The path forward, according to Khan and Mohsin, lies in rebuilding trust through genuine dialogue, people to people connections and equitable partnerships. “Rebuilding trust requires both nations to move beyond divisive politics. India must respect Bangladesh’s sovereignty and engage with it as an equal partner,” Khan said. Mohsin agreed, emphasising the need for India to rethink its media narratives and open all diplomatic channels.

Sadid summed it up, “We are tired of being treated like a puppet state. It is time for India to treat us as equals.”●