“We always live in fear”: In Bangladesh’s hills, army’s quiet war on a tiny Bawm nation

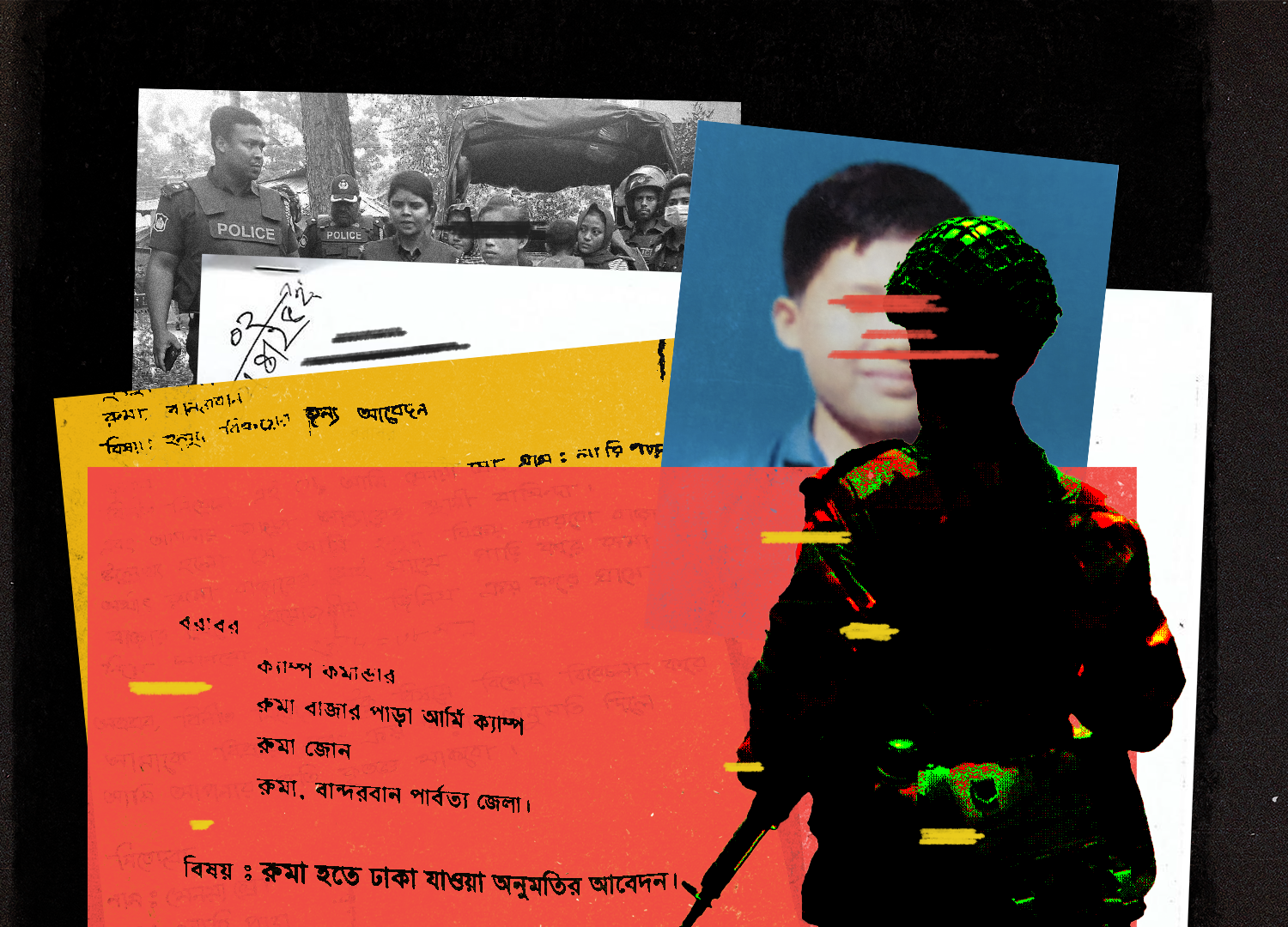

Security operations in Bandarban have targeted Bawm civilians, leaving at least 19 dead, including a 13-year-old, women and children in jail, villages deserted, and regular movement under military control.

On the morning of May 23rd 2024, soldiers purportedly searching for the Kuki-Chin National Front (KNF) moved through two adjoining hamlets in the remote jungles of Bandarban. By day’s end, a schoolboy was dead — seized, questioned and then shot at close range.

His parents were nearby.

“That morning, my son woke up very early. When he saw the soldiers, he ran. The soldiers caught him as he screamed in fear,” Jinger Moi Bawm, the schoolboy’s mother, said in a recent interview. “They dragged him away, beat him, and kept asking questions. Even after learning he was just a student, they still shot him. He cried out, ‘Mum, Dad’, before they killed him.”

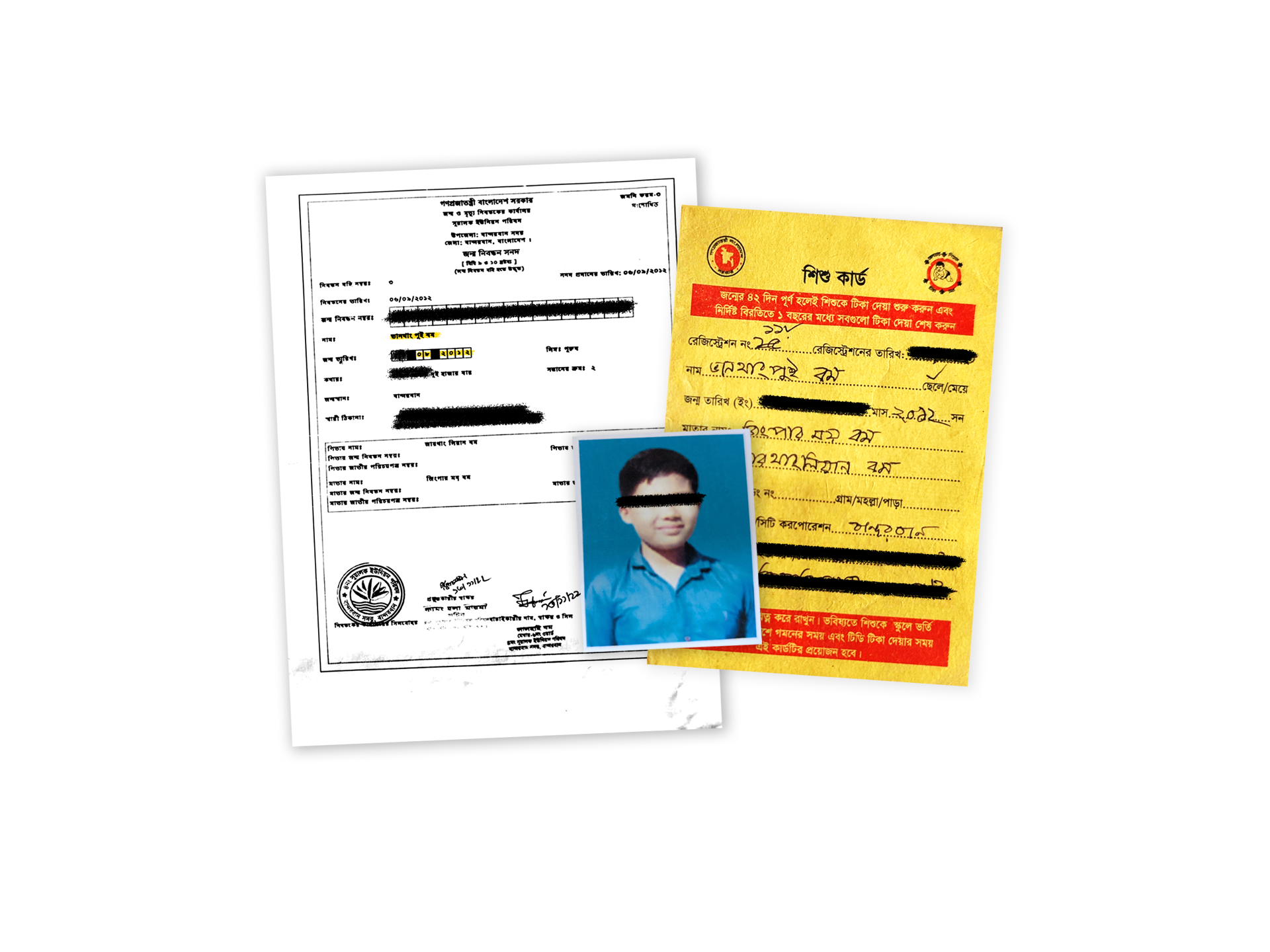

The killing of 13-year-old Van Than Pui Bawm has become a flashpoint in a little-known conflict that, a Netra News investigation finds, has claimed the lives of at least 19 Bawm civilians and shaken an indigenous Christian community of a little over 13,000 people.

The current anti-KNF army campaign intensified after April 2nd and 3rd 2024, when alleged KNF members robbed two banks, took a manager hostage, and looted firearms from nearby Ansar and police camps.

What began as a counterinsurgency has hardened into a quiet, grinding war that has devastated a tiny, reserved community, and left families searching for answers no one seems willing, or able, to provide. For the Bawm — arguably the most marginalised and impoverished among the dozen indigenous groups in the region — the present campaign is without precedent in recent decades.

The Chittagong Hill Tracts, of which Bandarban is a part, has lived under a sustained military presence since the 1970s, when an ethnic insurgency first took hold. A 1997 peace accord brought a measure of stability, yet the army has continued to wield significant influence in areas nominally under civilian authority.

The Kuki-Chin National Front (KNF), an ethno-nationalist group, emerged in 2017 seeking an autonomous region across parts of Bandarban and Rangamati for Kuki-Chin peoples — a colloquial umbrella for several small indigenous communities, including the Bawm. KNF’s leader, Nathan Bawm, was once seen as close to elements of the military; he was photographed alongside generals stationed in the area, even after, elders say, the organisation’s founding.

That arrangement ruptured in 2023 after an operation by the Rapid Action Battalion, an elite police unit. Since then, at least four soldiers have been killed in attacks attributed to KNF, and the military’s response has been brutal: at least 20 people, fighters or those otherwise affiliated, have been killed.

Yet interviews and documents reviewed by Netra News suggest the state’s campaign has gone far beyond targeting KNF, failing to distinguish between the group and the broader Bawm community. Nearly as many civilians have been killed and hundreds arrested — a strategy, dozens of family members, lawyers, politicians, activists and journalists say, intended to sow community-wide fear and panic. Tight movement restrictions imposed by the army have further deepened the sense of collective punishment across Bawm-populated areas.

A child branded a “terrorist”

On May 23rd 2024, when troops entered Sharon Para, a village in Bandarban where Bhan’s family lives, the operation appeared retaliatory; days earlier, two soldiers had been killed in an ambush attributed to KNF.

“We didn’t know there would be a raid,” said Jarthang Lian Bawm, Van’s father, recalling the suddenness of the army operation. “Gunfire erupted on one side, and on the other, we trembled in fear.”

At the time, Van Than Pui Bawm, a student of class six at Kalaghata Government Primary School in Bandarban, was in nearby forestland, where his family practised jhum cultivation, a slash-and-burn farming method on the hills.

Jarthang said troops took the body to a hospital for autopsy report, and later returned it via the local karbari (village head). “We never received the post-mortem report.”

The day after the shooting, the military’s press wing Inter-Services Public Relations publicly labelled the schoolboy as a KNF “terrorist” supposedly killed in a gunfight. A police inquest report further described Van as “approximately 20.” However, birth registration, nationality and vaccination documents reviewed by Netra News list Van’s age as 13.

The inquest, which identifies gunshot wounds as the cause of death, named two military personnel, Sergeant Masum Sheikh and soldier Nasir Uddin, as witnesses. In June 2024, the karbari who helped hand over the body and was listed as the first witness, Vluang Thon Bawm, was himself arrested — a move community members say is intended to intimidate witnesses.

Neither the ISPR nor the civilian interim government responded to detailed questions from Netra News.

A rising toll

Van’s killing is not an isolated case.

A coalition of indigenous journalists, lawyers and researchers — none of whom would speak on the record against the military — documented at least 39 Bawm deaths from gunfire by security forces across Ruma, Rowangchhari and Bandarban Sadar between May 8th 2023 and November 24th 2024. The list, reviewed by Netra News, identifies 20 as affiliated with KNF; the remaining 19 appear to be civilians with no ties to the group.

To corroborate this, Netra News spoke with relatives of 10 of these victims, consulted two senior public officials in Bandarban and Rangamati, several community elders, and senior figures in the United People’s Democratic Front and the Jana Samhati Samiti — rival ethnic groups to KNF with extensive rural networks. All confirmed the 19 had no political links, let alone militant past.

Among the dead were eight farmers, three preachers and five students, including Van. In none of the cases, relatives and community elders asserted, did the military and local authorities provide families with autopsy reports.

Additionally, three Bawm men — Lal Thelong Kim Bawm, Lal Sangmoy Bawm and Bhan Lal Royal Bawm — died in custody in Chattogram Central Jail.

Bhan Lal Royal Bawm, who practiced jhum cultivation and worked on a mango orchard, died on July 17th 2025, after being arrested more than two years earlier. He left behind a wife and two young children.

“My husband was taken from his workplace. We never saw him again. He is dead now. No one can tell me why,” Jingnun Moi Bawm, Royal’s widow, recently said in an interview.

Royal’s father-in-law, Lal Muntling Bawm, said poverty left the family unable to post bail or seek answers: “If you’re Bawm, they’ll detain you — whether you are at home or in the forest. There is no safety. Not everyone is a terrorist. Innocent people have been detained, even killed.”

‘Collective punishment’

Dang Jing Bawm, whose husband and daughter were imprisoned, said arrests have erased the line between militants and civilians. “Those who are KNF are being taken, and those who are not, too.” Her husband, Lal Than Khup Bawm, was arrested late at night on January 4th 2025 from the jungle. “He was living in the forest out of fear. When word of his hiding spread, he too was arrested.”

Their daughter, Sheuli Bawm, had been arrested eight months earlier. Medical reports shared by her family show she has thalassaemia and other chronic conditions.

“We once lived a good life — not anymore,” said Dang Jing Bawm. “Our husbands are getting arrested, our daughters too. One of my sons is in college, but I can’t send him to class. Another daughter is in seventh grade, and I can’t send her to school either.”

Families describe the situation as “guilt by association,” where simply being Bawm is conflated with KNF or Kuki-Chin ties.

“My husband is not KNF. He was taken from a church on May 2nd 2024,” said Parvin Moi Bawm, wife of detainee Ram Chonhsang. “I don’t really know what is happening — everyone in the Bawm community is treated as KNF. If they can’t find the men, they take the women and families. Even in jail, they call us the ‘KNF team’.”

Whether we admit it or not, militarisation of governance has become the foundational logic of the Bangladeshi state. In the CHT, this logic takes its most violent form, where the absence of a formal emergency has not prevented the reality of de facto occupation.

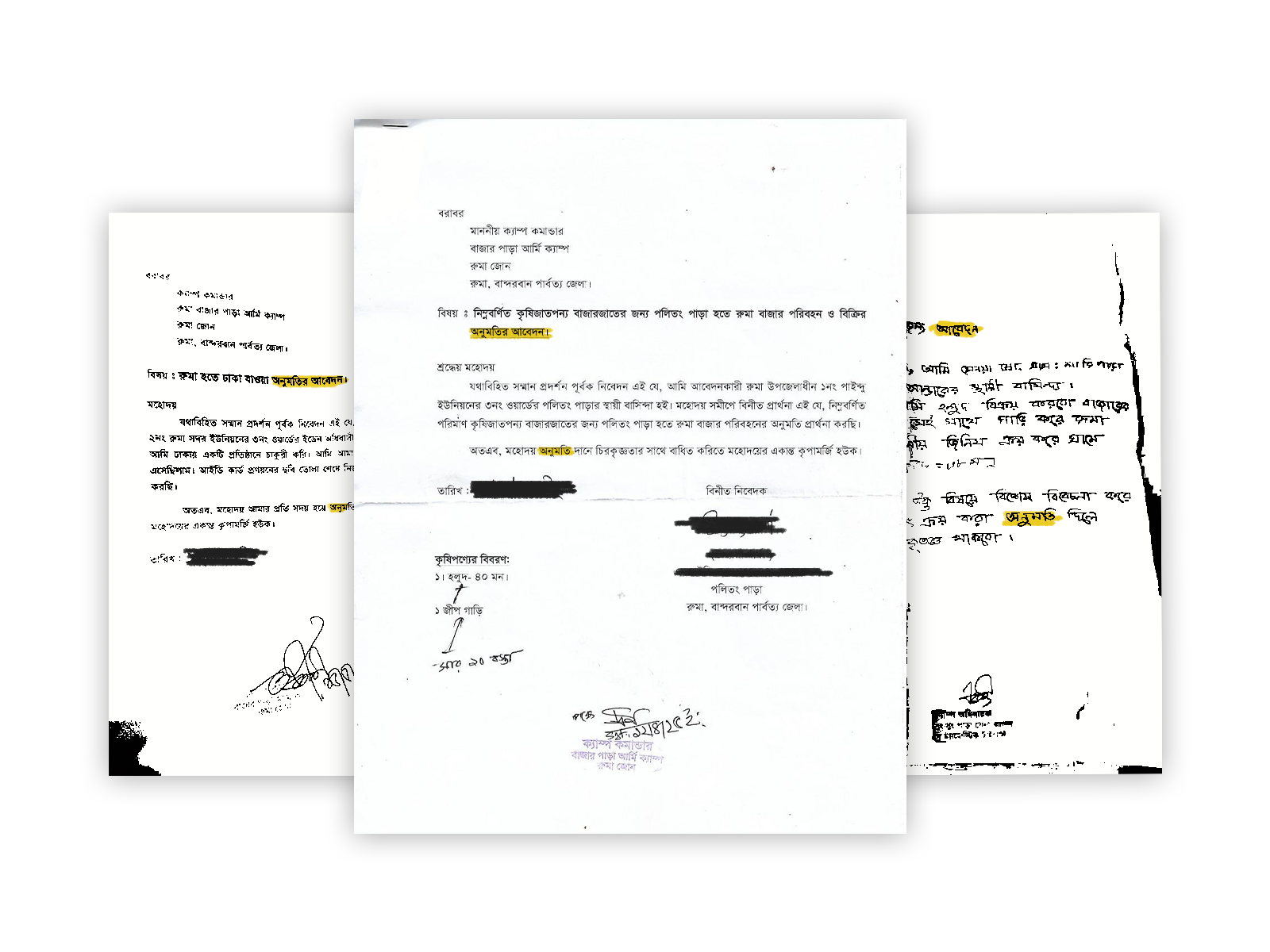

Residents say they must secure written permission from local army camps to buy essentials and face routine questioning at checkpoints en route to fields, orchards and markets.

Travel from Bandarban to Dhaka requires permits. Netra News reviewed three letters to a local army camp commander requesting permission to carry turmeric to a farmers’ market in Ruma — a type of restriction on civilian movement that experts say is highly unusual in peacetime Bangladesh.

“Entire villages are encircled by the army,” said Sara Hossain, a top human rights lawyer in Dhaka. “If crimes have occurred, specific individuals must be held responsible through lawful investigation. Instead, we are seeing collective punishment and prolonged detention.”

Amnesty International UK reported on May 13th 2025 that at least 30 Bawm women and children were among 126 people arrested in April–May 2024 without specific charges. As a result, six Bawm villages — Tai Khyang Para, Salaupi Para, Tindol De Para, Tamlao Para, Fainung Para and Luan Mo Para — are now empty due to the ongoing anti-KNF army operation, said local rights activist Jumlian Amla. “We are currently living in a culture of fear.

Detainees included a one and a half year-old, a four year-old and a woman who was eight months pregnant.

Netra News has identified at least 11 Bawm women held for more than a year. They typically face four cases each in spite of having no prior criminal records, according to their lawyer, Abdullah Al Noman. He said four of the detainees have thalassaemia, citing medical reports shared with Netra News; college identity documents show at least three are recent school or college graduates.

Detained Bawm women appear in court with their toddlers, escorted by police officers.

Court files reviewed by Netra News show the women face accusations including bank robbery, hostage-taking and stealing state weapons. Yet, at least one of the four complaints, filed by local Ansar official Emon Das Gupta, describes the perpetrators as “young men.”

“There is CCTV footage of the robbery that shows who robbed the banks,” Amnesty wrote in an urgent action letter to then-Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina last year. “Instead of using it to identify the perpetrators, your government is persecuting an entire Indigenous community.”

Only on August 24th have nine women, including Sheuli, and four children been granted bail after spending more than 500 days in jail without even a trial. Fourteen more women remain imprisoned.

It is unclear why lower courts refused bail for so long. Noman argued the women lacked any capacity to obstruct investigation, typically a key consideration for bail. “A person who must struggle for food and walk six kilometres to fetch water — how could she obstruct justice?” he said. Referring to the interim government’s reform agenda, he added: “If a family from a remote corner of Bandarban must travel to the High Court Division in Dhaka just to seek bail, what reforms are we discussing?”

Amnesty says senior advisers in the interim government — some former rights advocates — were also formally briefed about the arrests and detentions, including during an August 20th 2024 meeting at which indigenous rights activist Rani Yan Yan raised the matter with Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus.

A year on, Bawm communities report no protective measures and continued restrictions.●