“I was ready to die”: Between despair and defiance, a trans activist takes a stand for LGBTQ rights

By Saturday night, Sahara Chowdhury Rabil ended her nearly two-day hunger strike — her latest form of protest forcing a conversation on LGBTQ rights in Bangladesh. She first came to the spotlight in August this year for caricatures of two vocal anti-LGBTQ individuals.

On October 10th 2025, Sahara Chowdhury Rabil, 23, a trans woman and activist, stood alone in the rain at Shaheed Minar on hunger strike with a banner — perhaps a first of its kind protest in the country — demanding marriage rights for Bangladesh’s LGBTQ.

She later slept on the footpath under an umbrella. After discussions with the Dhaka University’s proctorial team, Sahara said she was allowed to continue her protest on campus grounds on the condition that her banner be removed.

On her second day of hunger strike, Sahara was flocked by a small group of supporters at Raju Vaskorjo near Dhaka University. Around 4 pm, her pale face, dry lips and dark circles around her eyes seemed to have no effect on her grit. “Denying marriage rights is an economic injustice. My demand is clear: LGBTQ individuals must be granted the right to marry,” she said. “Without the right to marry, people face financial hardships and remain socially marginalised.”

By Saturday night, Sahara ended her hunger strike — her latest form of protest for LGBTQ rights in Bangladesh. Sahara first came to the spotlight in August this year when she was expelled from her university. The expulsion, Sahara claimed, was a disproportionate response to the caricatures she drew and published on social media of two anti-LGBTQ influencers.

Sahara’s university years

Sahara enrolled in Sylhet’s Metropolitan University in 2022 as a student in the English department. In a few months, she transitioned and revealed her gender identity; the reception had been generally warm, she remembered. Sahara was one of the class toppers in her batch.

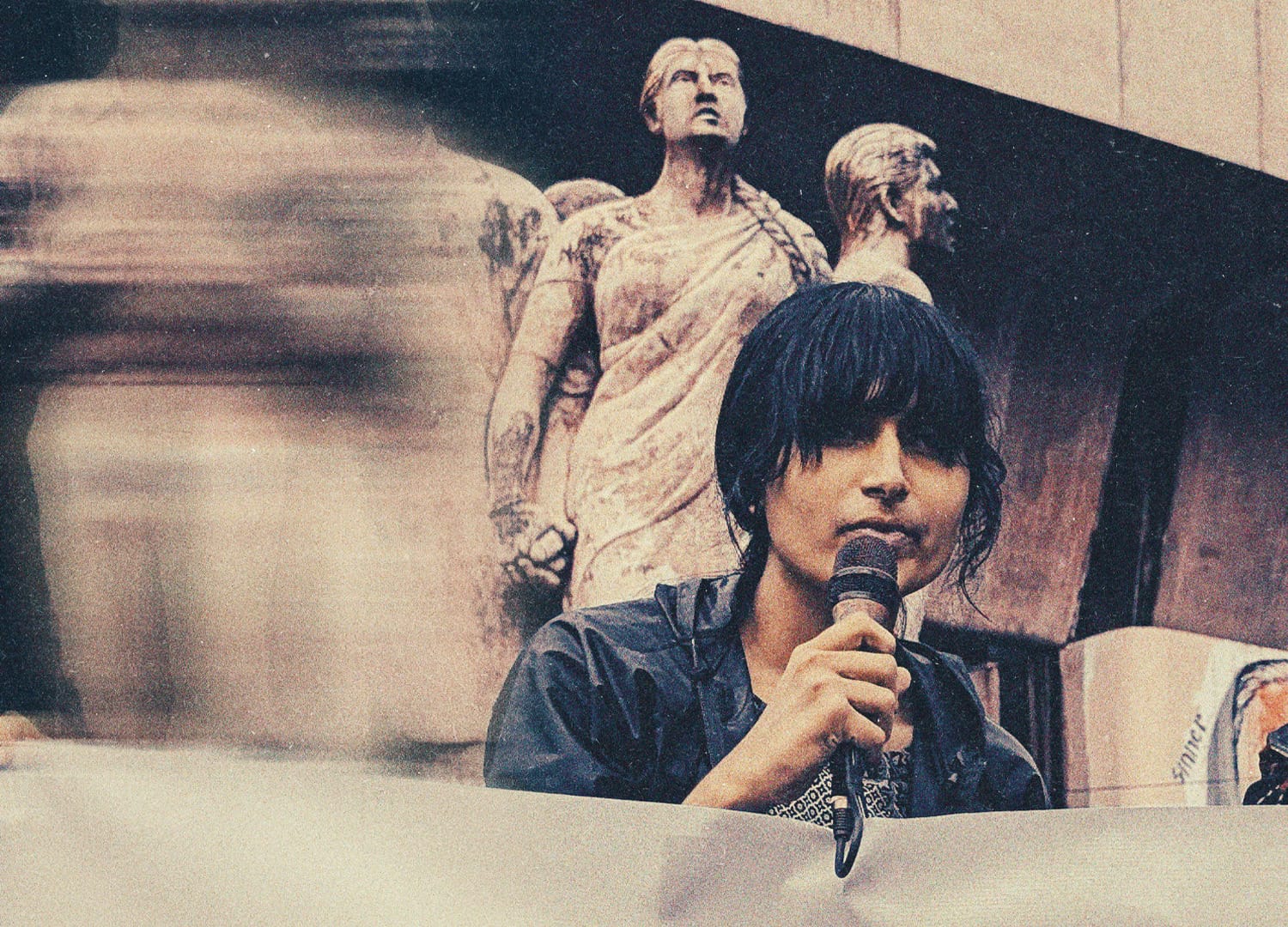

Last year, during the July Uprising, Sahara took part in the student protests, which saw the then-prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, ousted. In a video, she is seen speaking into a microphone on campus grounds, rallying support for the movement.

However, things changed. In February 2025, her classmates shared violent videos targeting transgender individuals, including the murder of Shila Chakma, a Bangladeshi transgender woman, in a student chat group. When Sahara protested, she faced threats and restrictions on restroom access, which she said were attempts to force her to stop attending university. She officially informed the head of her English department in an email on February 4th about the matter. In response, she was verbally told by the university to stop advocating for LGBTQ issues online.

Parallely, Sorowar Hossain and Asif Mahtab Utsha, faculty members at private universities in Dhaka, continued to express their anti-LGBTQ stance on their social media platforms with a large following. In several cases, both tended to target Bangladeshi members of the LGBTQ community by posting about them, drawing their audiences’ attention to the individuals.

“Even during the July movement, LGBTQ people fought together on the streets, yet Asif questioned why transgender people should be included in memorials for martyrs,” said Sahara.

In July, Sahara updated a 92-page manifesto advocating for LGBTQ rights and calling for violent retributions if and when those rights are denied — this part also mentions Sorowar and Asif. She had previously published the manifesto in April on her Facebook account. On August 11th, Sahara drew graphic caricatures of Sorowar and Asif, calling for their murder, and published them on her Facebook account, tagging them.

Consequently, Sahara was expelled from Metropolitan University on August 13th. “I haven’t received any personal notice or disciplinary hearing from the university. Initially, they told my guardian not to send me to classes. Later, I found out about my expulsion only through a public post.”

To date, Sahara has been unable to collect her transcripts from the university due to a lack of co-operation from the university, she claimed.

Between defiance and despair

The caricatures were meant as satire, Sahara explained in an interview with Netra News in August, drawing on Bangladesh’s tradition of using provocative language in protest. “In 1971, extreme slogans were used; during the July movement, protesters also used harsh language. That’s why I personally don’t think my caricatures fall outside the realm of satire.”

Legal experts note that publishing material online that incites violence can constitute a criminal offense under the law; and, at the same time, student expulsion from an educational institution must follow proper legal procedures.

Metropolitan University’s proctor, Sheikh Ashraful Rahman, justified the expulsion, citing repeated warnings and student safety concerns. “Her being transgender was not a factor. The decision was made to protect the institution from potential serious harm.”

He also added, “All the arms she carried were documented and sent to the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), who were satisfied with our records. We held multiple proctorial meetings and departmental discussions regarding her conduct and issued warnings. Her being transgender was not a factor in the decision. Rather, the concern was that other students would feel threatened if she remained in class. She was also given ample opportunity for self-defense.”

Netra News’ multiple requests to the university for proof of documentation of the said warnings or counseling issued to Sahara were not met.

Samina Lutfa, Associate Professor in the Department of Social Sciences at Dhaka University, stressed that a student’s primary identity is that of a student. “Every person has the right to live safely as a citizen of their society. If someone like Sahara Chowdhury is excluded from this, on what basis is the state granting rights to its citizens? If you are supporting marginalised groups, regardless of religion, caste, or gender, it is the university’s responsibility to ensure their safety. I do not need to consider someone’s personal identity to manage institutional operations.”

Sahara stressed that her manifesto does not solely advocate violence. “I conducted a material analysis of the harm faced by Bangladesh’s queer community due to the lack of legal rights and protections.”

Md. Muntasir Rahman, an LGBTQ rights activist, echoed the sentiment. “Transgender people are marginalised from the start. They often cannot get justice from the police, face eviction from hostels, and lose jobs or housing due to online hate campaigns. Society has always labelled LGBTQ people as ‘weird’ or ‘bad,’ but they are not allowed to speak for themselves.”

Rahman also warned of broader consequences: “Hate against LGBTQ people leads to denial of opportunities in education, employment, and housing, and in extreme cases even murder. For instance, in Tangail, a hijra was killed during a Puja festival. It all stems from the propagation of hate.”

When Sorowar and Asif were asked if their anti-LGBTQ narratives on social media put the group at risk, they both defended their stance. Sorowar Hossain explained his posts as “awareness campaigns,” emphasising legal and social concerns while Asif Mahtab Utsha stated that what LGBTQ activists call “rights” are criminalised under Bangladeshi law. Both filed police reports against Sahara in response to her caricatures and said that the publication of the manifesto constituted criminal behavior.

“People communicate suffering through their own style and language. When someone feels trapped or unable to exercise their rights, they may respond in extreme ways,” said Dr. Kamruzzaman Majumdar, professor of clinical psychology at Dhaka University, drawing parallels with other extremist groups in Bangladesh.

Dr. Nazia Haque Oni, founder of the mental health platform Psychnee, stressed the toll of distress. “While she has the right to study and express herself, threatening or violent imagery indicates mental distress. In such cases, psychological support is essential.”

Earlier, Sahara stood by what she had written in her manifesto. “I stated in my manifesto that if the police arrest LGBTQ people solely for being LGBTQ, I would bomb police stations, and I have no remorse. If a demographic is targeted just for who they are, I believe it is my duty to resist it. Laws are not always just or ethical, in the United States, Black people were legally enslaved. When the law is unjust, it becomes a human duty to oppose it.”

On October 11th, Sahara again spoke about her manifesto — this time she pointed to the latest updates. “In my earlier version, I mimicked the tone often used online by those who issue threats. I myself have received many such threats, but it was intended as satire. Some readers interpreted it as a threat, so I later removed the explicitly aggressive parts and refocused on the queer rights that are needed.”

On Sunday, after the two-day hunger strike, Sahara reflected on the physical toll. “It’s like being hit by a truck. I’m in a death-like state.”

However, her grit did not wane. “I knew I wouldn’t win marriage rights overnight. But I was ready to die to show how uncaring the state is. When people began publicly demanding LGBTQ rights, including marriage, without fear or legal reference, that was already a victory.”●