Living under militarisation

An indigenous photographer documents the lives of people in the hills under military rule to bring to light a reality that does not find space in mainstream media.

Every month, Mashruk Ahmed will curate an instalment of a photo-story series that questions established power discourse, featuring photographers who explore gaps, absences, and silences in Bangladesh’s socio-political records.

In this sixth edition, we feature photographer Denim Chakma, who has been documenting “the silent occupation” by the army and military rule in Bangladesh’s Chittagong Hill Tracts for several years. He shared some of his work from his project called “Living Under Militarisation”, where he used a mixed media method, the technique of combining photographic elements with other artistic materials to create a single artwork, due to the sensitivity of the subject and the impossibility of photographing events such as crossfires, late-night military operations as they happen. You can find the fifth edition, “The Rohingya know where home is”, here.

There was an army camp next to my village. I used to wake up to the sound of gunfire. My childhood was spent witnessing military rule. At one time, I was terrified whenever I saw soldiers. So, when I speak from that place, “Living Under Militarisation” project is not a work born out of inspiration, but out of a sense of responsibility.

I work from that sense of responsibility, taking on the challenge it demands. To me, the camera is a tool of resistance; a symbol of struggle.

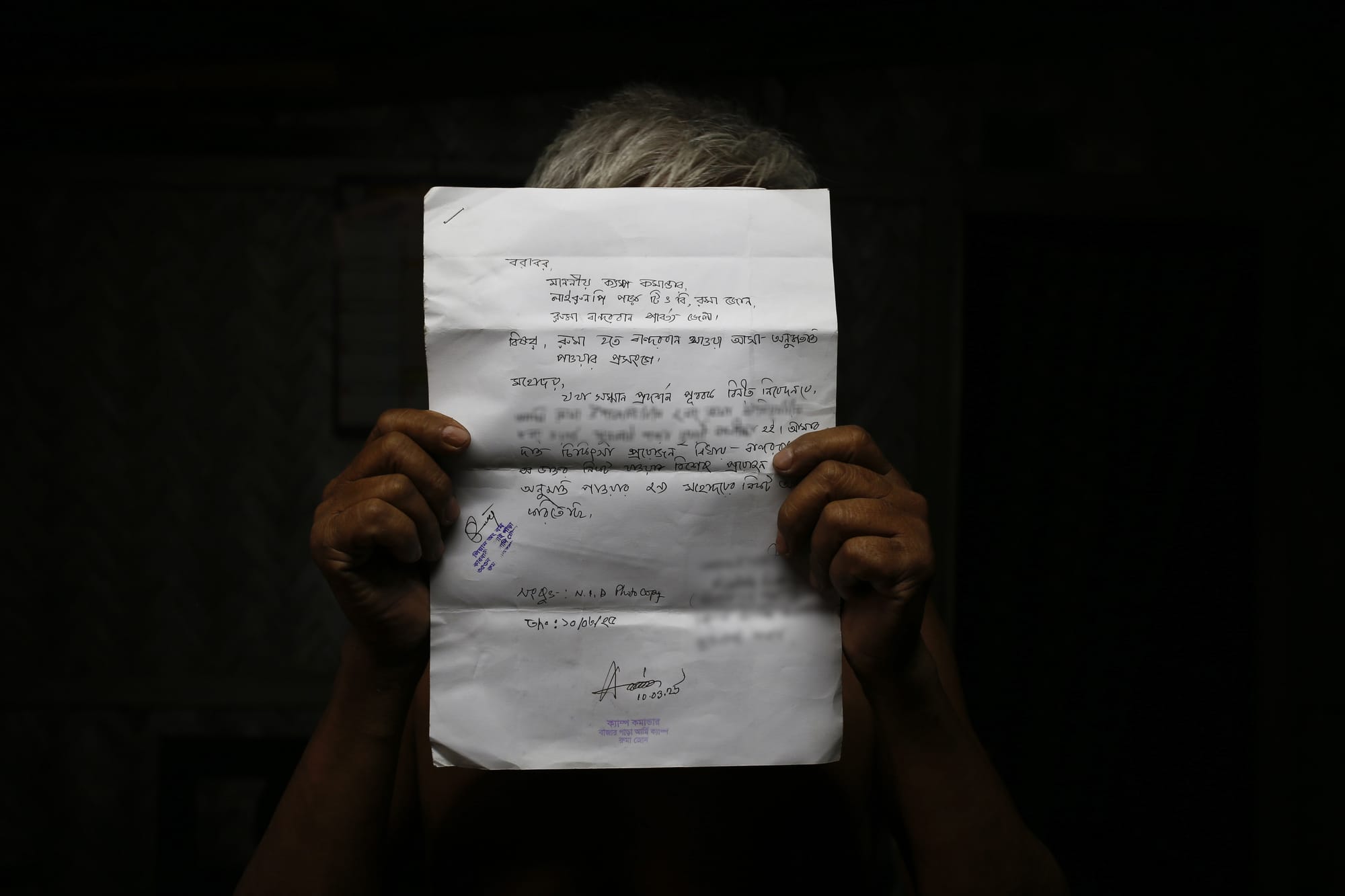

Militarisation is an everyday political reality for the indigenous hill people. Visually representing this reality is one of the greatest challenges when it comes to the hills. That’s why I use my work to question the state’s silent role in sustaining militarisation.

In each of my artworks or photographs, you will notice a crisis — one that might make people reflect. When people reflect, they try to understand the problems. I use tools very subtly in each of my works. For example, in this project, I have used tools to reveal the cruelty of militarisation subtly.

If you go to the Chittagong Hill Tracts, you will see army checkpoints at regular intervals. You will also notice signs saying “Photography Prohibited.” Confiscation of cameras and being prevented from taking photos are things you constantly have to face.

Often, oppression is hidden behind the veneer of beauty. To me, the beauty of the hills is not the landscape itself. The beauty of the hills lies in the people who live there. If we cannot reach the reality of the indigenous people of the hills, then the concept of beauty has no true foundation. For us, beauty means visually representing the truth of that reality.

The state-sanctioned damage, death and threat

The "civilisation" that was destroyed in the 1960s through the Kaptai Dam project was not replaced. It was shattered, and its people were left to survive on the fragments. The "continuous state of crisis" you describe—the environmental collapse, the transportation hardships, and the deep-seated pain—is the enduring, six-decade-long legacy of the Kaptai Dam.

A boundless, deep pain as deep as the blue waters of the Kaptai Dam is held in the hearts of the hill people, carried from generation to generation.

Just imagine, the Kaptai Dam had not been built. What would be the art and culture of the people of Chittagong Hill Tracts? Café aromas would drift through the air, while the city would be a dazzling display of colourful lights. Mountains, adorned with wildflowers, would mirror the joyful essence of the hill people. Unrestrained by fear, they'd embrace every emotion, celebrating life with a fervour that makes the whole landscape pulsate with vitality. The entire mountain is like the pulse of life. A grand festival where life is full of breathing space.

Due to the reduction in forest cover, streams and springs are drying up. Water scarcity is prevalent in most areas during the dry season. Due to the Kaptai Dam, the primary means of transportation in most areas of Rangamati is by boat or launch. However, due to the decreasing water depth of the dam, travel becomes a hardship during the dry season. In many places, boats can no longer operate when the water recedes. Although the government has taken initiatives to dredge Kaptai Lake on several occasions, these efforts have not been implemented. Day by day, the water of the Kaptai Dam is becoming polluted.

And that is not all. Through militarisation, particularly since Operation Uttoron began in 2001, the Chittagong Hill Tracts have been turned into a prison. Whenever you step out of your house, you have to answer to the army at checkpoints. In no other district of Bangladesh do people have to show their national ID card, but in the Hill Tracts, you must carry it at the checkpoints. Along with that come constant questioning and harassment—these have become part of the daily routine of the indigenous hill people. It has effectively become a state-sanctioned prison.

Let me give the recent KNF issue as an example. In a joint forces operation to suppress so-called KNF “terrorists,” about 43 people were shot dead. Various media outlets reported that the KNF members were terrorists. But among those 43 people, around 19 were ordinary Bawm civilians—including a 13-year-old child. Yet, the mainstream media portrayed all of them as terrorists. If you think about it deeply, you’ll see that the media too legitimises militarisation.

Among indigenous youths, there is certainly a tendency to resist oppression. However, this resistance is suppressed through constant surveillance and censorship by state forces. Many indigenous youths have faced—and continue to face—persecution for trying to organise movements. As a result, any large-scale movement against oppression is not allowed to emerge. Moreover, divisive politics already exists in the hills, and this politics of division is also orchestrated by the state.

To put it plainly, because of militarisation, the rich culture of the indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts is being placed under constant threat.

This place was a Tripura indigenous village. A road for the border highway was constructed by destroying the hill over a period of two years. The Tripura indigenous village was evicted. It was then renamed Zig Zag Point for tourists. Photo: Denim Chakma

In the midst of tourism

In the Chittagong Hill Tracts, so-called development and tourism are forms of state aggression. The kind of development carried out there has never benefited the indigenous people. Instead, it has pushed their lives, nature, and very existence toward destruction. Forests are cleared, indigenous villages are evicted, and hills are cut down to build roads. Once the construction is done, tourism is promoted. In essence, development and tourism in the Chittagong Hill Tracts are state-planned projects aimed at the displacement of indigenous communities.

Due to prolonged state surveillance in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, the indigenous people have been psychologically turned into prisoners. This surveillance has been made a part of their everyday lives. Just as a prisoner gradually becomes accustomed to life behind bars, the entire Chittagong Hill Tracts has been turned into a prison through military control—and the indigenous people are being held captive there as if they were criminals.

There are some stories that people want to tell but cannot—or are not allowed to tell. I believe those stories must be told first. If we fail to visualise these stories, the problems will remain unresolved.

What lies ahead?

After seeing “Living Under Militarisation,” I hope the audience will be able to understand the pain and suffering of the indigenous hill people. The cruelty of militarisation in the hills will compel their conscience to respond. Perhaps it will find a place in history as a document. If my work helps to establish indigenous rights, then I believe it will have fulfilled its purpose.

As a documentary photographer and artist, I want to stand as a witness to history. At the same time, I want to bring history to people in the form of stories. I have also been involved in activism for a long time.

Ultimately, the hope is that the next generation of Indigenous artists and photographers from the CHT will be brave and innovative. That they will build strong, collaborative platforms to amplify their collective voice and that their art will not just be about identity and justice, but will be an act of identity and a tool for justice—work that sparks dialogue, demands accountability, and helps secure a future where their communities are not just seen, but are truly heard.●