An ideologue returns with a louder voice

No longer a cleric confined to a little-known mosque, Mufti Jasimuddin Rahmani returns to public life — this time in the heart of secular Bangladesh

The fall of Sheikh Hasina’s rule last August, followed by an uprising led largely by students, was hailed by many in Bangladesh and abroad as the beginning of a new democratic chapter. But as the dust settles, the country’s volatile political vacuum is drawing in figures long relegated to the extremist margins.

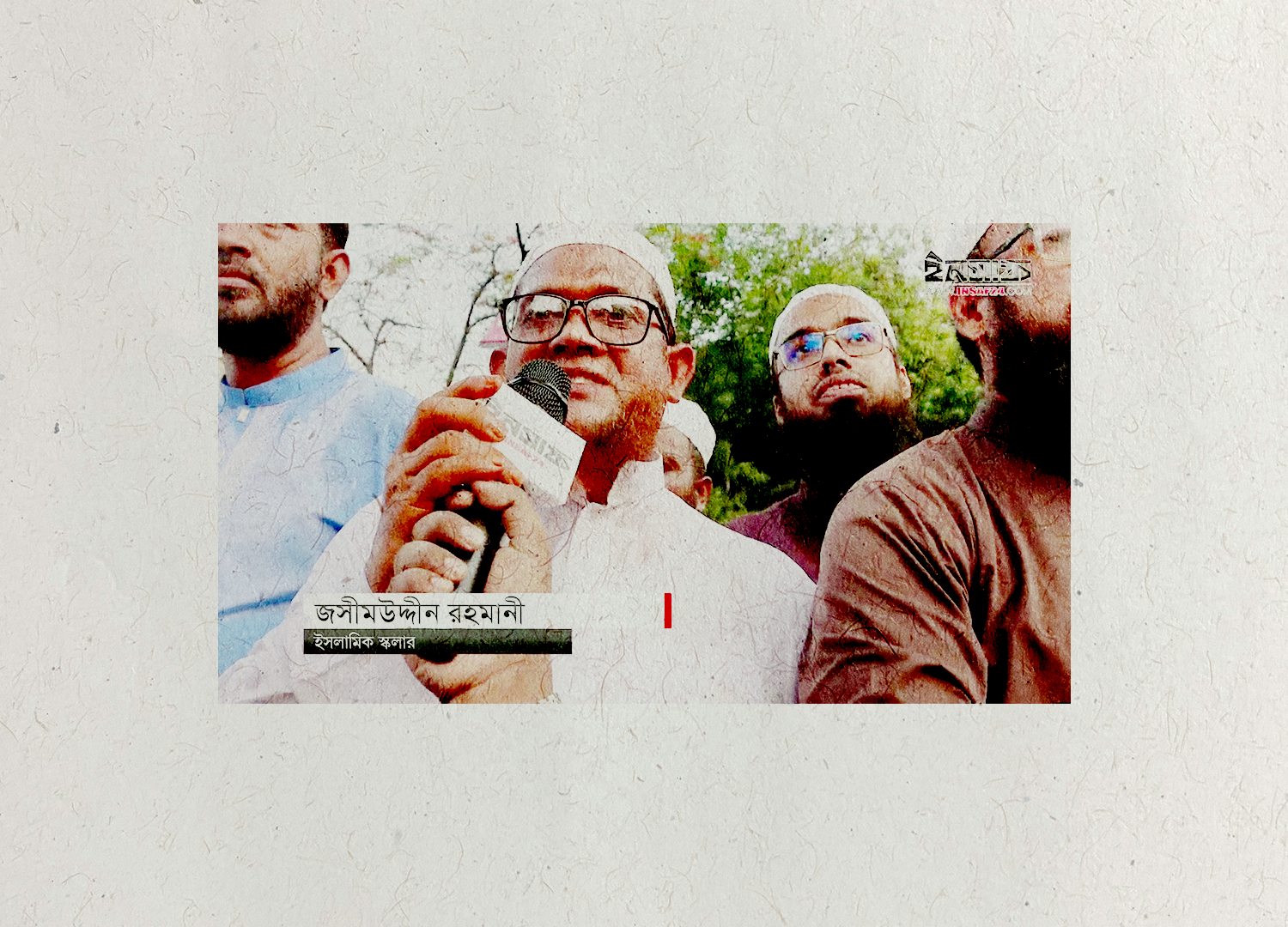

This week, Mufti Jasimuddin Rahmani — a radical cleric once imprisoned for inciting extremism and described by the US-based Counter Extremism Project as a follower of Al-Qaeda ideologue Anwar al-Awlaki — appeared at a rally calling for the dissolution of Hasina’s Awami League. Flanked by supporters, Rahmani led a roadside prayer, delivered fiery remarks, and joined chants demanding the party’s formal ban.

“They didn’t hesitate to hurl abuses against Allah and His messenger,” Rahmani told the crowd, referring to the Awami League. “That alone is reason enough to ban them,” he said, as his followers chanted slogans invoking religious unity.

He later warned the government: “If you don’t ban the Awami League, the people will take over and do it themselves.” The government, led by Muhammad Yunus, caved. On May 10th, following days of mounting pressure, the interim administration banned the Awami League’s activities under anti-terrorism laws, citing the need to protect witnesses in cases implicating party leaders and to “safeguard national sovereignty.”

Leaders of the newly formed National Citizen Party (NCP), which backed the protest, privately distanced themselves from Rahmani’s appearance. They insisted he had not been invited and said they had no authority to remove him from a public gathering. His appearance nonetheless signalled the extent to which far-right Islamist voices are asserting themselves in the political order taking shape after Hasina’s ouster.

The NCP has emerged as a key power bloc in the new landscape, rallying support among a group of students and wielding prominence among mainstream political actors. Yet, the inclusion of Islamist factions — among them Jamaat-e-Islami, Khilafat Majlish, and other hardline groups and figures — at recent NCP-backed demonstrations, has unnerved many observers who fear a drift towards majoritarian religious politics.

Rahmani’s presence was especially striking.

Once presented by Bangladeshi security agencies as the spiritual head of Ansarullah Bangla Team, a group they alleged had links to Al-Qaeda, Rahmani was jailed in 2015 for inciting the murder of an athiest blogger, Ahmed Rajib Haider. Though he denied the charge — and, in a recent interview with BBC Bangla, claimed that “Ansarullah Bangla Team never existed” — his writings leave little doubt about the inherent extremism of his views.

In his book Unmukto Tarbari (The Unsheathed Sword), Rahmani advocated the death penalty for those who insulted the prophet Muhammad, citing Quranic passages. The book, reviewed by Netra News, specifically called out the writings of blogger Haider — who was later killed by suspected extremists and whose murder Rahmani is accused of inciting.

A counterterrorism expert who reviewed Rahmani’s sermons and spoke to Netra News on condition of anonymity described the cleric as a “careful but clear promoter of violence,” who would not issue direct calls to action, but instead frame such acts as religious obligations.

“He is smart, so he didn’t say, ‘go and kill,’” the expert said. “He’d say, ‘this is what God expects from a good Muslim.’”

The US-based Counter Extremism Project has assessed Rahmani as a follower of Anwar al-Awlaki, the late American-born propagandist for Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. A 2023 academic paper by Ali Riaz, now chair of the constitutional reform commission under the interim government, described Rahmani’s disciples as part of a “fourth generation” of Islamist militants spreading global jihadist ideologies inspired by doctrines of al-Awlaki.

Other scholars have analysed his rhetorical craft. A 2022 paper by security expert Asheque Haque described Rahmani as “a master narrator,” noting how his sermons often invoked Quranic and Hadith sources without explicitly referencing jihadist predecessors, thereby blending radical themes into mainstream religious discourse.

His influence extended into state institutions as well. A former Bangladeshi counterterrorism official told Netra News that three police officers assigned to monitor Rahmani’s mosque sermons in Dhaka became radicalised themselves, later deserting the force to join his cause.

Despite his notoriety, criminal proceedings against Rahmani stalled after the 2015 case. As evidence linking him to specific acts of violence proved thin, he was granted bail in most of the remaining cases. He was ultimately released in August 2024, days after the collapse of the Hasina regime, as his sentence for incitement had expired years earlier.

A top government official told Netra News that Rahmani’s release had been raised in bilateral meetings with high-ranking US officials. The government, still reeling from the collapse of the Hasina regime, maintained that the cleric was freed during a period of near-total breakdown in law enforcement and before the newly formed council of advisers — many with little experience in governance — had fully consolidated control of the state.

Officials say Rahmani has remained under close surveillance since his release and point to recent statements in which he appeared to temper some of his earlier positions, including a public call for the protection of Hindu temples.

Still, since walking free, Rahmani has cast himself as a defiant survivor of Awami League repression — his narrative sharpened by years behind bars, often without judicial sanctions. In the new political climate, he now commands a broader platform and a louder voice than he ever did in the shadowed corners of a little-known mosque.

His recent re-emergence coincided with growing public demands to formally outlaw the Awami League — a party accused of ordering thousands of extrajudicial killings and disappearances during its near 16-year-long tenure.

Broader alliance

The government’s announcement to ban the Awami League’s activities followed a tense series of events. On May 8th, former president Md. Abdul Hamid — a longtime Awami League figure — left for Thailand for medical treatment, prompting speculation of a possible backroom deal to rehabilitate the party. A subsequent story by Netra News, citing government sources and documents, revealed his departure was cleared by top military intelligence agencies.

That evening, NCP supporters began gathering outside the Chief Adviser’s residence. By morning, they were joined by Shafiqul Islam Masud, a youth leader from Jamaat-e-Islami, and other Islamist factions.

The following day, after Friday prayers, a broad alliance of Islamist groups — including Jamaat-e-Islami, Khilafat Majlish, Islami Oikya Jote, and Khilafat Andolan — converged on Dhaka’s Shahbag intersection, the symbolic heart of secular protest movements in the past.

Among the demonstrators were members of Islami Chhatra Shibir, the student-wing of Jamaat, who were heard chanting in support of Ghulam Azam and Motiur Rahman Nizami — two former Jamaat leaders convicted of war crimes for their roles in commanding and assisting pro-Pakistani militias during Bangladesh’s independence war in 1971, and who went to their deaths without expressing remorse.

Rahmani arrived shortly before dusk and addressed the crowd.

He stayed for a little over an hour before departing, eyewitnesses said. But his appearance — and the cheers that met his message — made clear that Bangladesh’s political transition, born of a broad coalition of student-led revolt, is now being shaped not only by the forces that brought Hasina down, but also by those long waiting in the shadows to reshape the nation’s identity in their image.

But by the following evening, a flicker of resistance surfaced.

Mahfuj Alam, a former student leader now serving on the interim government’s council of advisers, publicly called on Jamaat-e-Islami to apologise for its role in the 1971 war. He appeared to describe the chants by Jamaat supporters at the rally as an act of “sabotage”.

Hours later, Alam posted — and then deleted — a fiery message on Facebook, warning: “Those who deploy civil society groups to preserve pro-Pakistani sentiments, you will suffer more than your predecessor razakars and collaborators,” referring to the paramilitary groups that aided the Pakistani military during the war. “Wherever the pro-Pakistanis are, they will always be targeted. Until death.”

At the protest site in Shahbag, tensions played out in real time.

Social media footage captured a striking divide: as some NCP supporters began singing Bangladesh’s national anthem, a group of Islamist demonstrators — some with black bands inscribed with Arabic calligraphy wrapped around their heads — attempted to drown them out, shouting over the anthem in a bid to silence it.●