What NYT got right — and missed — in Bangladesh Islamist story

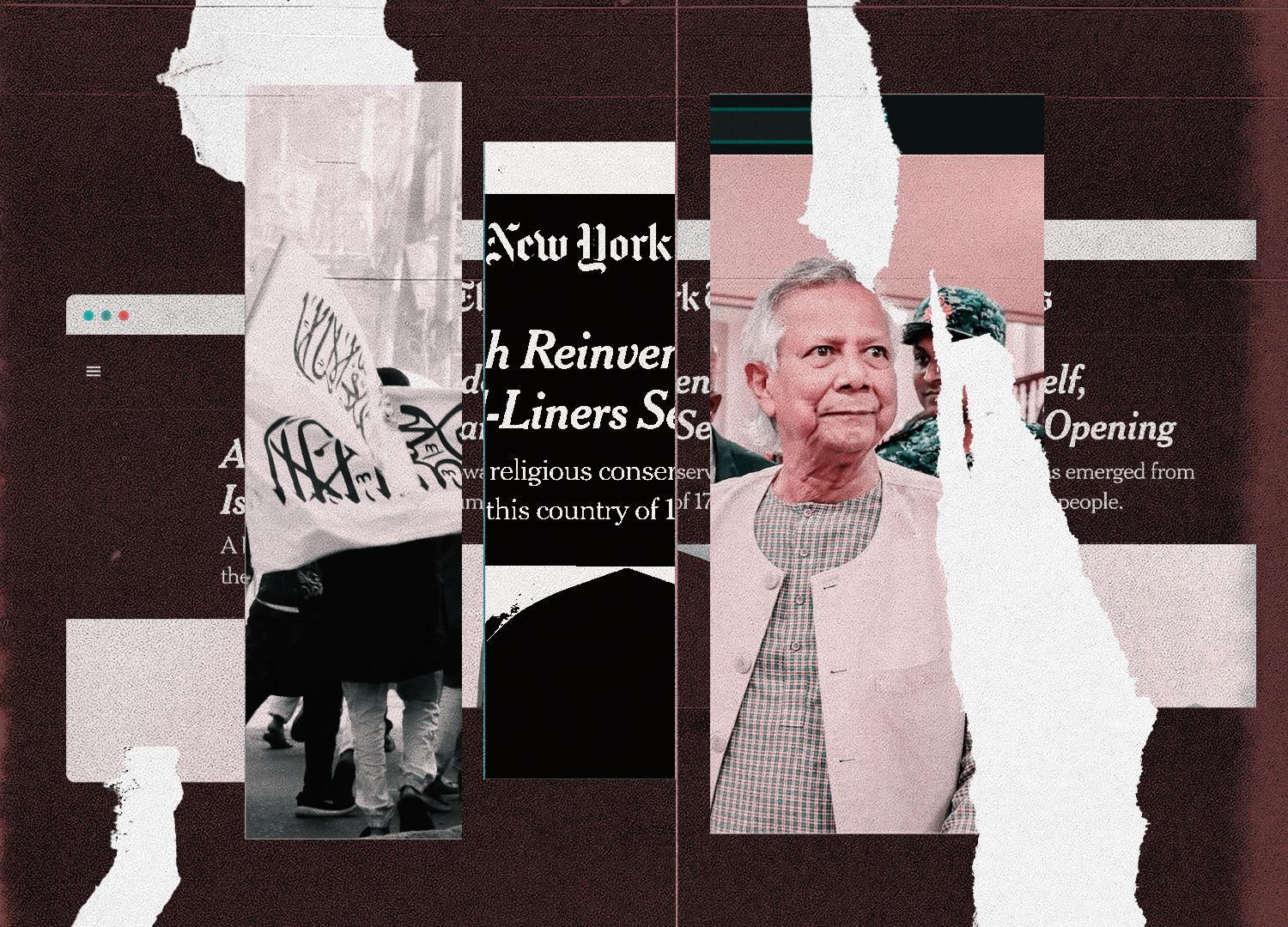

The New York Times' recent report on Bangladesh’s Islamist resurgence was fair and timely — but not without blind spots.

The New York Times’ recent article on Bangladesh’s hard-line Islamists — who seem to be looking for an opening after the sudden fall of Sheikh Hasina — was a balanced piece of journalism.

It went beyond the headlines: reporters talked to student activists, political figures, government officials and even some of the more hard-line campaigners on the ground to show how previously repressed Islamists now see an opportunity in the power vacuum. This is about as thorough as you’d expect from quality reporting.

Yet, the piece attracted a strong response from the government’s own fact-checking team, CA Press Facts, which, according to Netra News’ reporting, isn’t without its own flaws. The government’s Facebook page labelled the Times article as “misleading”, as if it was up to the government to decide what counts as proper journalism.

Of course, even the most earnest reporting has its limitations — especially when conducted by roving foreign correspondents and tailored for an international readership.

Editorial choices, the implicit biases of reporters and sources alike, catering to an audience that knows little about Bangladesh, and the sheer impossibility of capturing every viewpoint within a confined space can all affect the final narrative. This piece, titled “As Bangladesh Reinvents Itself, Islamist Hard-Liners See an Opening,” was no exception.

For instance, the article mentioned that Islamist demonstrators threatened to “carry out executions with their own hands” if the government did not punish those who disrespected Islam. In reality, these demonstrators were mainly calling on others to take matters into their own hands — a subtle but important difference.

In the same vein, the article refers to an outlawed group — presumably Hizb-ut-Tahrir — organising a large march demanding an Islamic caliphate. This group isn’t known for advocating vigilante executions; in fact, while problematic in its own right, it has rejected the more extreme methods favored by groups like the Islamic State or Al Qaeda. (It’s for this reason that the UK tolerated Hizb-ut-Tahrir’s presence until quite recently.) Yet in the article, these groups are presented as if they were part of the same trend.

The report also overlooks that — while the government has struggled to curb the rise of these Islamist undercurrents overall — it did arrest some of the organisers of the Hizb-ut-Tahrir rally, and the group hasn’t been seen organising public protests since.

Likewise, it misses how divisive figures such as Jashimuddin Rahmani — who was linked (though he strongly denies any connection) to a once-active local Al Qaeda affiliate — urged followers to steer away from violent tactics when addressing issues like blasphemy.

Omissions like these, though likely inadvertent, leave out a current of restraint and nuance within the Islamist discourse.

There’s also a section suggesting that some officials and politicians believe the government might replace secularism as the constitution’s defining feature with the term pluralism, a change that will ostensibly push the country in a more religious direction.

This claim is presented without any supporting quotes, so it’s harder to judge. But in reality, the prospect of amending the constitution seems unlikely, especially as major parties are currently pushing for an early election.

Moreover, the idea of replacing secularism with pluralism has met with staunch opposition from some extremists, who view it as a cover for endorsing LGBTQ or transgender rights — a stance that, arguably, secularism itself doesn’t inherently guarantee. As one Islamist commentator put it on Facebook, “it’s like out of the frying pan and into the fire.” That context directly undercuts the article’s suggestion that dropping secularism would be inherently illiberal.

The piece then touches on the much-talked-about cancellation of a girls’ football match in a rural town, which was disrupted by protests organised by a little-known local cleric — whom the Times, to its credit, managed to track down and interview.

While the incident has been somewhat blown out of proportion — given that thousands of girls’ matches are held annually in Bangladesh — it does highlight the ongoing tension in a society shaped by patriarchal expectation of female modesty.

The article went on to note that the match was rescheduled with tight security but frames this not as a government effort, but as evidence of a growing societal extremism. That gave an unfair impression of Bangladeshi society. In fact, the cancellation triggered a nationwide outcry so intense that some protest organisers were forced to apologise, leading to the match being rearranged.

The piece also contends that the government, led by Muhammad Yunus, hasn’t pushed back hard enough against extremist forces. That may be accurate, but then again, a government’s ability to do so is limited when key institutions like the police and army are only scantly cooperative — a point the article also rightly acknowledges. Those were contradictory narratives that were left unexplained.

Still, there were many moments when the article captured nuanced developments.

It pointed to the weakened state of the police after Hasina’s fall and to the military’s increasingly fraught relationship with the new government that promised accountability for the law enforcement’s past excesses. It also gave voice to female student activists, who rightly expressed concern over emboldened anti-women zealots following the revolution they helped spark. Their grievances are legitimate and hard to dismiss.

The piece also underscored, rightly, the dilemma faced by a government that must outperform its authoritarian predecessor in safeguarding free speech — a challenge that may inadvertently allow space for extremist voices that stretch the bounds of conventional norms.

The article could even have gone further in detailing the emboldening of hardcore Islamists.

One example would be the impact on Sufi Muslims — a community that venerates saints and has recently endured a wave of shrine desecrations by extremist elements. While law enforcement has made some progress in curbing the trend, it remains a vital chapter in the broader story of Islamist resurgence — one the Times could have addressed, and one that would have been difficult for its critics to refute.●