“Our land is our mind”: The trauma facing indigenous and coastal women

The psychological toll of climate change — and the disproportionate burden it places on coastal and indigenous women — remains one of the most overlooked aspects of climate discourse around Bangladesh.

For cyclone survivors in Bangladesh’s coastal villages, their memories of the storms are still fresh. “The tide was three to five times higher compared to other storms. Everything was washed away. I was floating on wood [a raft] in chest-deep water with my two children. We were soaked. There was no dry place,” said Anandini Munda, recounting cyclone Aila’s destruction in 2009. “There was also no cyclone centre.”

At the time, Anandini — a member of the indigenous Munda community in Bangladesh’s southwestern region — lived in Datinakhali village near the coast in Shyamnagar upazila, Satkhira district. But the cyclone displaced Anandini, forcing her to relocate more inland, leaving behind familiarity.

The majority of the Munda community, consisting of about 3,000 people, lives in riverine areas near Sathkhira and Sundarbans, according to the Sundarbans Indigenous Munda Organisation, and under the constant threat of climate change.

For cyclone survivors, abundant in Bangladesh’s coastal region, anxiety is a constant companion. “Whenever the clouds gather and a storm brews near the Sundarbans, fear grips everyone’s hearts,” said Morjina Akter, referring to a large mangrove forest nearby. “We pack up our belongings, ready to move, wondering whose building we’ll climb into this time, whose house will take us in.”

Last month, Morjina, about 30, sat outside her home in the Satkhira village of Nil Dumur. She has been displaced twice by cyclones. Her mustard-coloured floral salwar kameez belied the story she told: the wrath of Sidr, a supercyclone which made landfall on November 15th 2007, devastating coastal Bangladesh.

She remembers the road and houses going under water; she remembers how people survived holding on to trees, and those who drowned beneath upturned boats. Days later, the body of an acquaintance was found. “The eyes were eaten by maggots. Small children’s bodies were floating at the roadside.”

She recalls a local landlord’s daughter, too. “She was pregnant, and had a small child. All [...] died together. Two more people died trying to save the child.”

Sidr’s storm surge rose up to 20 feet, affecting 31 districts in Bangladesh and killing at least 6,000 people, according official government figures. However, Bangladesh Red Crescent Society tallied 10,000 casualties — this was one of the two supercyclones, one cyclone and 11 major storms, to batter the southwest between 2007 and 2024. These communities live not only on the frontlines of climate change but their exposure to sea level rise, cyclones and saltwater intrusion remains unmatched. Yet, they remain largely outside the sphere of the state’s protection.

That’s not all.

The psychological toll of climate change — and the disproportionate burden it places on coastal and indigenous women — remains one of the most overlooked aspects of climate discourse in Bangladesh, even as the country ranks ninth on the global climate risk index. Netra News interviewed 17 coastal and indigenous women across nine villages in Satkhira District and three indigenous villages in Rangamati District — as well as experts, to capture the depth of the climate emergency through these perspectives and beyond.

Bangladesh Cyclones (2007–2024)

| Name | Category | Date | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclone Remal | Cyclonic Storm | 24 May | 2024 |

| Severe Cyclonic Storm Mocha | Severe Cyclonic Storm | 14 May | 2023 |

| Cyclonic Storm Sitrang | Cyclonic Storm | 25 October | 2022 |

| Super Cyclonic Storm Amphan | Super Cyclonic Storm | 20 May | 2020 |

| Very Severe Cyclonic Storm Bulbul | Very Severe Cyclonic Storm | 9 November | 2019 |

| Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Fani | Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm | 3 May | 2019 |

| Severe Cyclonic Storm Mora | Severe Cyclonic Storm | 30 May | 2017 |

| Cyclonic Storm Roanu | Cyclonic Storm | 21 May | 2016 |

| Deep Depression Komen | Deep Depression | 30 July | 2015 |

| Cyclonic Storm Mahasen | Cyclonic Storm | 14 May | 2013 |

| Severe Cyclonic Storm Aila | Severe Cyclonic Storm | 25 May | 2009 |

| Very Severe Cyclonic Storm Sidr | Very Severe Cyclonic Storm | 15 November | 2007 |

While state support for these communities has been minimal, the warnings are stark. If sea levels rise by just one more meter, 13 per cent of Bangladesh’s southern coastal land could be submerged, according to a recent report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The World Bank warned in a 2022 assessment that 13 million people in Bangladesh may be displaced by 2050 as a result of the adverse impacts of climate change, such as rising sea levels, loss of agriculture, and water scarcity.

A mind under threat: eco-anxiety, panic and fear

“By late afternoon, the water had risen so much that you would not believe it. You would lose your mind seeing it,” said Sokhina Begum, recalling the day Cyclone Aila struck in 2009.

“It was up to the chest before I knew it. [Now] we all feel terrified whenever clouds gather.”

In Bangladesh’s disaster-prone coastal areas, 33 per cent of adults and 21 per cent of children suffer from mental illness, according to a iccdr,b study. Climate change–related disasters have increased by 46 per cent since 2000. Bangladesh Health Watch’s 2024 research highlights a clear link between climate impacts and mental health in coastal communities.

To the east of the island village of Golakhali lies the Sundarbans; to the west, the Kalinchi and Madar rivers; to the north, the Dhajikhali. But there are no embankments here, no cyclone shelters — no defences against the ferocity now routine.

“The river never rose like this before,” said Golakhali’s oldest resident Swaira Mondol, “Oh dear, everything gets washed away. We live on boats. I keep worrying when the houses will break, and where we’ll have to move next.”

Swaira Mondol was displaced at least three times by cyclones.

Professor Mohammad Ali, deputy director at the National Institute of Mental Health, said households stripped of homes and livelihoods experience immense psychological pressure: Acute Stress Disorder, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and anxiety disorders are common. “Hopelessness and depression is the severity of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or Acute Stress Disorder. This is especially common among pregnant mothers and children. In pregnant mothers, there is also a risk of miscarriage. The unborn child may also be affected if the mother is depressed.”

Research from the Grantham Institute for Climate Change suggests that with every 1°C rise in temperature, the risk of suicide increases by about 1 per cent. “Many show suicidal tendencies,” Professor Ali added. “Having lost everything, thoughts like ‘What is the point of living anymore?’ also arises. They become extremely fearful and anxious, have nightmares and sleep disturbances at night.”

As awareness of the planetary crisis grows, “eco-anxiety” has entered clinical vocabulary, said Dr Caroline Hickman, a lecturer in climate psychology at the University of Bath. “It is a new mental health syndrome. This is really important because although this is being felt globally, the areas that it’s impacting where you will see mass migration are mostly in the Global South.”

“So in India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, lots of Africa, the low-lying Pacific nations, Vanuatu, the Marshall Islands, they are being massively impacted because it's no longer possible to live in those places,” she added.

Hickman argues we must examine the impact on daily life — eating, sleeping, school, work, farming — and then the emotional and cognitive effects. “If it impacts your daily living, then it’s no longer safe for you to live there, and that forces you to move, to migrate… to run away, to flee, because it’s physically unsafe, not just emotionally or cognitively unsafe.”

“Children, women, and older people will feel it most severely as they don’t have the capacity to tolerate those increased levels of heat.”

Salt in the water, salt in the wound

“Women work five to six hours daily in the enclosures [likely shrimp farms]. We fish in the river for three to four hours. The saline water causes skin diseases, uterine problems, and miscarriages,” said Anandini Munda in Mundapara, Shyamnagar.

A 2021 survey by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) indicated that 73 per cent of residents in Ashashuni and Shyamnagar Upazilas of Satkhira consume unsafe, saline water. Furthermore, 52 per cent of ponds and 77 per cent of tube wells are deemed unfit for potable use. As a result, hours are squandered on water procurement, simultaneously escalating health hazards.

“During situations like Aila and Sidr, when we have our periods, we have to use saline water on our sensitive skin. This causes problems in that area, and we become sick. We don't even have drinking water, so what can we do for menstrual management? We have to use that same saline water,” added Anandini.

In Burigoalini, Satkhira, Fatima Akter hurried along a path lined by houses to her right, water to her left—clutching a kalshi, the rounded clay vessel, tight against her hip as if it were a child. Sweat beaded on her upper lip. “I haven’t even eaten rice today because of the water crisis. I have to fetch some water first. I’ll drink water first, then I can eat rice.”

“We have no other way but to drink salty water in the months of Chaitra and Baishakh [summer]. We have to drink it just to survive. We suffer from diarrhoea and vomiting right after drinking this water. Then we have to buy saline and medicine,” she added.

Across vast areas—Golakhali, Gabura, Lebubunia, Patakhali, Padmapukur, Neeldumur, Koikhali, Mathurapur, and South Kadamtali—families are locked in an unequal struggle with saline intrusion. Drinking saline water causes stomach ailments, sores, itchy skin and raised blood pressure, especially among women and children, leading to more frequent clinic visits.

“Our periods become irregular,” said Sanjida Khanam, a young student from Nildumur village. “That’s why even adolescent girls in our area take pill-type medicines, the ones that married women take as contraceptives. It causes mental unrest. The mood becomes irritable. It gets difficult to focus on studies. One feels like staying alone all the time.”

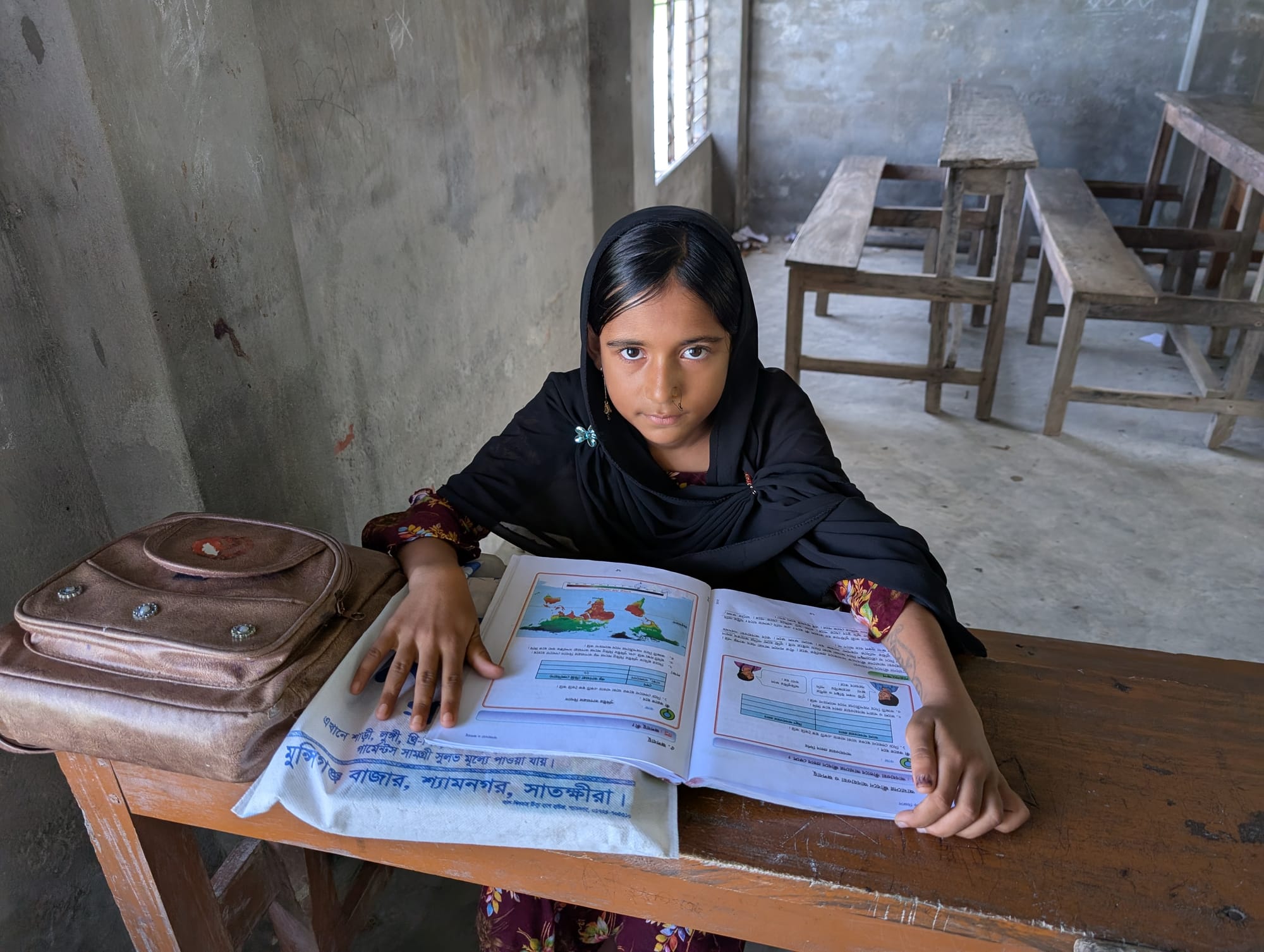

Children interrupted

A 2023 study by the International Rescue Committee found child marriage in Bangladesh’s coastal areas has risen by 39 per cent due to more frequent natural disasters. In Patakhali, 19-year-old Nazmun Nahar smiled shyly as she tended a clay stove stacked with firewood. “I wanted to be a doctor. I could have served people. At the very least, I could have become a nurse.”

Her mother resisted marriage, she remembered, but her father insisted and ultimately prevailed. She was married at 14 and became a mother a year later.

UNICEF reports that the education of 35 million Bangladeshi children was disrupted in 2024 due to extreme heatwaves, floods, and cyclones.“When Cyclone Aila struck [in 2009], we experienced flooding here for one and a half months,” said Abu Rayhan Mallik, a teacher at the Islamiya Dakhil Madrasa, an Islamic middle school, “Many children lost their books. They come and say, ‘Sir, I don’t have my books. They were swept away in the flood, what will I study?.”

In the same district, a young school student, Nazmun Nahar Maria, said “It’s difficult to study when it’s so hot. I get headaches. I cannot walk. Everyone feels the same.” According to UNICEF’s child-focused Climate Risk Index, Bangladesh ranks 15th globally. Over 10.9 million children are at risk, a quarter under 5.

The weight on indigenous women

In Rangamati, one of Bangladesh’s few hill districts, the threat is not rising seas. Its elevation offers insulation from coastal surges, but climate change did not spare it. Indigenous farmers practising shifting cultivation (jhum) describe a different, chronic crisis.

One recent afternoon, around 1.30 pm in Dighlibak village, Saapchori Union, Shrilokkhi Chakma walked under a merciless sun, a gamcha wrapped around her head and a seagrass basket on her back with the day’s harvest. “It was not this hot before. Now the heat is unbearable. I ask, has the sun’s heat come down to the ground? No one answers.”

She is fed up: “Pests are increasing. They destroy all the rice. I have a plum garden, and pests ruin everything.” Fellow farmer Sandhya Rani Chakma described how yields have collapsed. “If we planted turmeric, we got turmeric; if we grew rice, we got rice. Back in the day, yields used to be good without fertilisers. Now, if we grow chilli or eggplant, they all die. Crops don’t grow if we don’t use fertilisers. Rainfall has become irregular now. Our crops fail because it does not rain at the right time.”

Extreme heatwaves, drought, floods, soil infertility, and unusual pest infestations now dominate daily life of indigenous women farmers in Rangamati; a lot has changed—for the worse.

“All of our incomes have decreased. Diseases are increasing in our hills. Family tension, work-related tension, everything increases our worries. Pregnant women are even more anxious, which affects their children,” said Kuntali Chakma.

The women say they receive no government assistance.

If development support were provided effectively, the environment could be protected, argued Raja Debashish Ray, chief of Chakma Circle. “Local councils here, or even in our traditional systems… There are activities that help protect water, forests, and biodiversity. If those could be implemented, then not only would the people survive, but water and forest resources would also be preserved. But our policymakers, the Ministry of Environment and Forests, the Forest Department, they do not understand these things.”

Beyond the hill districts, Bangladesh endured its longest heatwave in 76 years last April—23 consecutive days that scorched three-quarters of the country. That same month, Jashore recorded 43.8°C, the second-highest temperature on record and the hottest in half a century.

“Areas like Khulna and Rajshahi that are on the western side are particularly heat-prone. However, this situation is changing and spreading across much of the country,” said Khandaker Hafizur Rahman, a meteorologist at the Bangladesh Meteorological Department. “We used to see that the monsoon would begin in June, but in recent years, we have not been getting the expected rainfall. The impact of climate change is clearly visible in our seasonal variations.”

The price of inaction

“It [the house] keeps breaking apart again and again. The biggest was Aila. Then there was Bulbuli, after that it was Amphan or something. During Aila the roads were destroyed, water rushed into houses and drowned everything. There is only one cyclone centre, even if we all share, there’s never enough space,” said Jyotsna Begum, nonchalantly, while cutting vegetables at her home in the afternoon in coastal Shyamnagar’s Patakhali village.

Jyotsna has been displaced five times.

Bangladesh’s long period of authoritarian rule, which collapsed last August, left vulnerable communities without political voice. Now, as electoral democracy stirs back to life, scepticism runs deep. In Golakhali, an island village, the oldest resident, Swaira Mondol, has little faith. “During elections, they’ll come running like mad: ‘Give me your vote.’ That’s when they show up. Once the election is over, so is their interest. During the campaign, they’ll call you ‘mother, sister’. But after voting, they won’t even recognise you.”

Eric Solheim, former executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, says Dhaka cannot look away. “Number one: strengthen and accelerate all the normal preparations for catastrophes, like building houses on pillars, making centres where people can take refuge, and not just people but also the husbandry because that makes you have a future after a huge extreme weather event.”

He argues that government, business and civil society must act together. “There is no place outside Bangladesh for people to go. It’s not as if India or another country would take in millions of refugees. Everything should be focused on how climate refugees can be resettled within Bangladesh.”

But beyond physical safety, infrastructure and livelihoods, there is a less visible crisis: mental health. “We need to think about how to help people manage their climate anxiety so that it becomes a motivating force rather than a paralysing or disempowering force,” said Susan Clayton, Professor of Psychology and Chair of Environmental Studies, College of Wooster. “One of the most important things we can do to help people is to provide them [with] ways to find social support and opportunities to connect with others. This could be as simple as creating spaces for members of a displaced community to come together with other people from the community they left behind — or perhaps forming new communities if that’s not possible — by providing people places to come and talk, share their stories, their challenges, and their responses to the event.”

Vered Eyal Saldinger, a peace and environmental activist, thinks creating strong communities is key. "It can start from local authorities, local government [...] reaching out to specific personalities who are very dedicated to local government and empowering them; you can start some change locally, in small villages".

For Solheim, also Norway’s former environment minister, the blunt reality is unavoidable. “At the end of the day, Bangladesh must prepare to shoulder most of the burden itself, even if that’s completely unfair. The emissions per capita in Bangladesh may be one twenty-fifth of the emissions per capita of the United States, yet it will have to bear most of the consequences or costs of the global climate crisis.”●

This story was produced with the support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.