Protesting the violence in the hills

A photographer witnesses the unfolding events following the news of an alleged rape of a Marma school student in Khagrachari.

The news broke on September 23rd 2025. By the following day, people — mostly students — took to the streets to protest the gang-rape of a 12-year-old Marma student in Singinala, Khagrachari. I went out to cover the movement. The protestors demanded the arrest and punishment of the culprits. There was a lot of visible anger among them. And even though there are risks of peaceful protestors being apprehended, something I have seen happen in the past, people continue to take it to the streets.

September 24, 2025: Local indigenous women took to the streets in Khagrachari Sadar to protest the rape of an 8th-grade Marma girl and demand the arrest of the culprits. Photo: Denim Chakma/Netra News

I have been documenting this “cycle” for many years now: following the act of rape of an indigenous woman — in some cases, murder too —civilians protest, clashes erupt, violence ensues; and the army takes measures to clamp down on the protests. For instance, checkposts are laid out, phones get checked, even social media accounts.

On September 25th, a road blockade was enforced by Jumma Chhatra Janata, an indigenous umbrella group that’s sprung up recently. Then I heard of Ukaynu Marma’s detention. He is the student leader who led the blockade and was picked up by the army and released after a few hours of detention on September 25th, according to a well-known local blog post in CHT News. By the following day, I reached Dhaka and covered the protest rally conducted on Dhaka University campus grounds. Later, protests were also held at Shahbagh.

September 24, 2025: Parbatya Chattogram Pahari Chatra Parishad (PCP) and Hill Women's Federation (HWF) held a protest procession and rally in Rangamati Sadar. Photo: Denim Chakma/Netra News

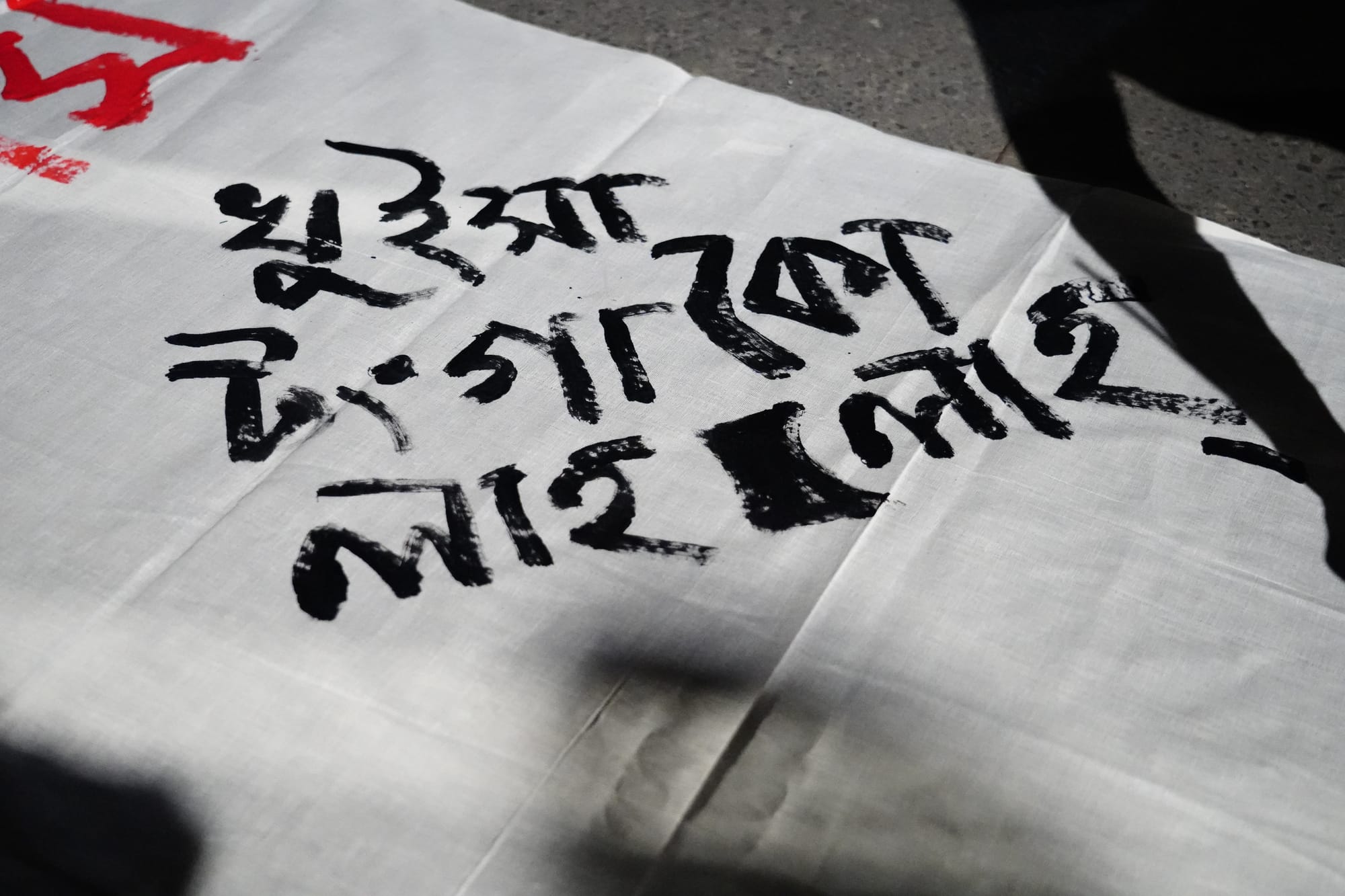

September 25, 2025: A half-day blockade was observed in Khagrachari District. Photo: Denim Chakma/Netra News

In Khagrachari, everything got worse. Following the protest program, violence erupted mainly in Khagrachari Sadar and Guimara Upazila on September 27th and 28th. Homes, shops, and businesses in the indigenous-dominated Ramsu Bazar area were set on fire. And, reportedly, three Marma youth of Guimara Upazila were shot dead. The Jumma Chhatra Janata sought an independent probe into alleged army-settler violence.

The district administration imposed Section 144 in Guimara. Many have left their villages in fear of arrest — this is also something we saw last year in September 2024.

September 26, 2025. An anti-rape grand rally was held in Khagrachari District Sadar. Demands were made at the rally for the security of indigenous women. Photo: Denim Chakma/Netra News

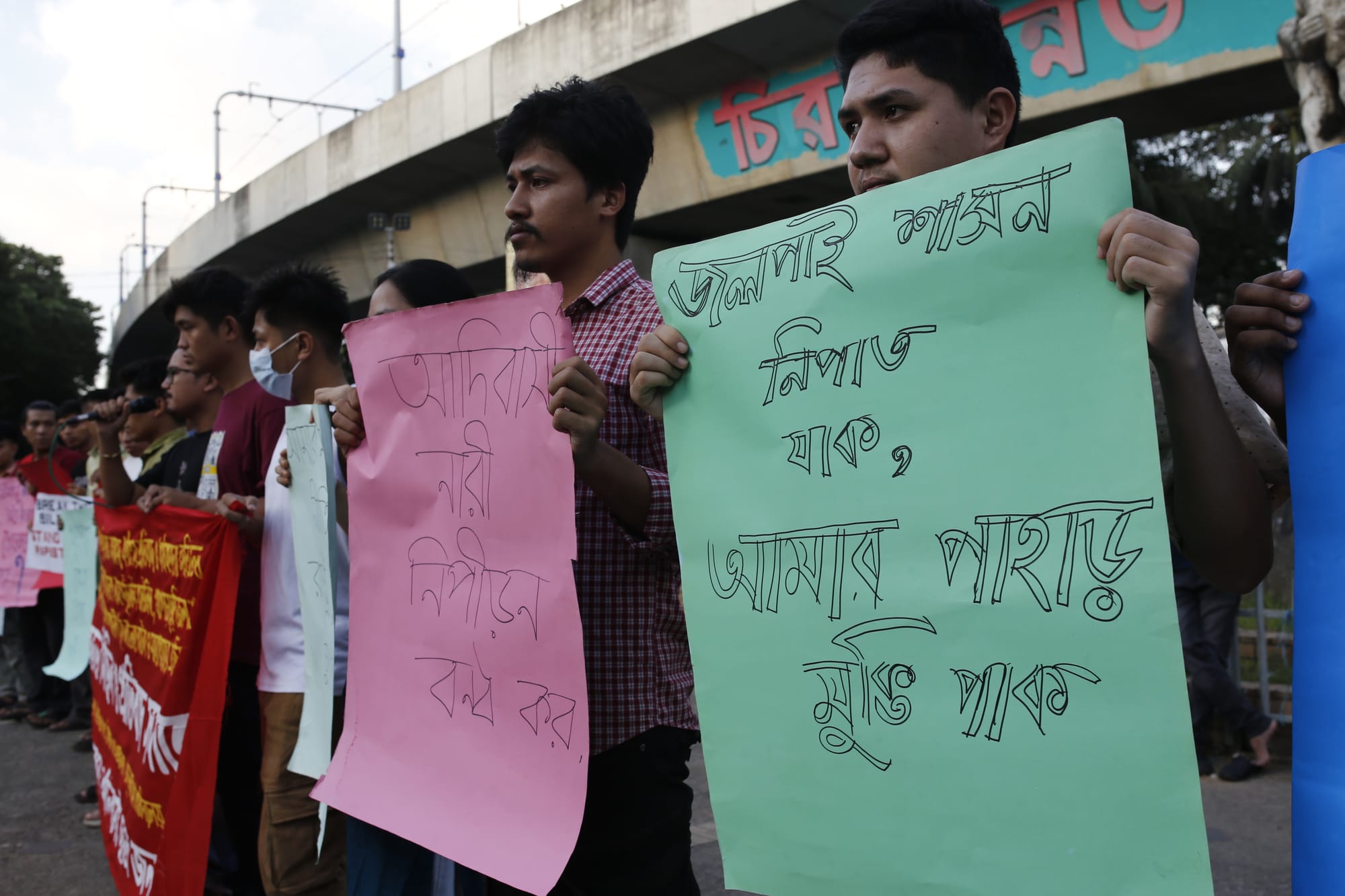

September 26, 2025. Adibashi Chatra Jonota held a protest rally in front of the Raju Memorial Sculpture, located near Dhaka University, chanting the slogan, “We Want Justice.”

September 28, 2025. Indigenous students and rights activists marched at Dhaka University's Aparajeyo Bangla, Shahbagh, and the TSC area of the capital to protest the killing of three indigenous people by gunfire. Photo: Denim Chakma/Netra News

More recently, in May this year, when the deceased Chingma, 29 — after being gang-raped and murdered – was brought to Bandarban sadar hospital for an autopsy from Thanchi, I spoke to the person in charge of the autopsy. I was told the report would come in about two weeks, but there was no report. These are only two examples; there are certainly more, and in many of these cases, I have witnessed first-hand the unfolding events that follow.

I have been working as a photojournalist for about eight years. I can tell you that this is not easy work in the CHT. Not only that we cannot (local journalists) do our jobs with ease, but other outlets [outside of CHT] cannot reach us, they get barred from entering; access is barred or limited for journalists — and not only “outside” journalists, but even local journalists have to work and move with extreme caution. For instance, no local journalist will be able to do the Bawm story.

In this case [September 2025], no national media outlet could reach the site immediately. I would say news coverage should be made possible, and the points of censorship — and there are many — need to be eliminated.

On October 1st, a government medical report found no sign of rape in the case of Khagrachari’s Marma girl. However, such reports are often not conclusive, may contain errors, and can even be altered under government pressure. Jumma Chhatra Janata has suspended the road blockade, and the police filed three cases over the Khagrachari violence.●