A lost generation: Rohingya youth barred from education

To be Rohingya is to stand at a cruel crossroads: risk death, violence and arrest in pursuit of education, or resign to a life where learning is forbidden.

Mohammad Ayrshad moved from village to village with his family when the military crackdown began in Arakan, Myanmar, on August 25th 2017. In the thick of the chaos, the tenth-grade student hoped conditions would stabilise soon enough to sit for his matriculation exams, the highest degree Rohingya students were allowed to obtain.

But violence caught up with them at every turn. “I even convinced my family to stay. But when my four-year-old brother became ill, I had no choice but to flee with them,” Ayrshad, now 25 years old, recalled.

Ultimately, Ayrshad had to embrace life as a “forcibly displaced Myanmar national” in Cox’s Bazar’s Balukhali camp, where education was limited to basic, informal learning. Access to Bangladeshi schools or universities was barred. Movement outside the fenced camps was prohibited.

In 2022, a glimmer of hope emerged. The Myanmar government announced that only those students who dropped out of the upper secondary level shall be eligible to sit for the matriculation examination.

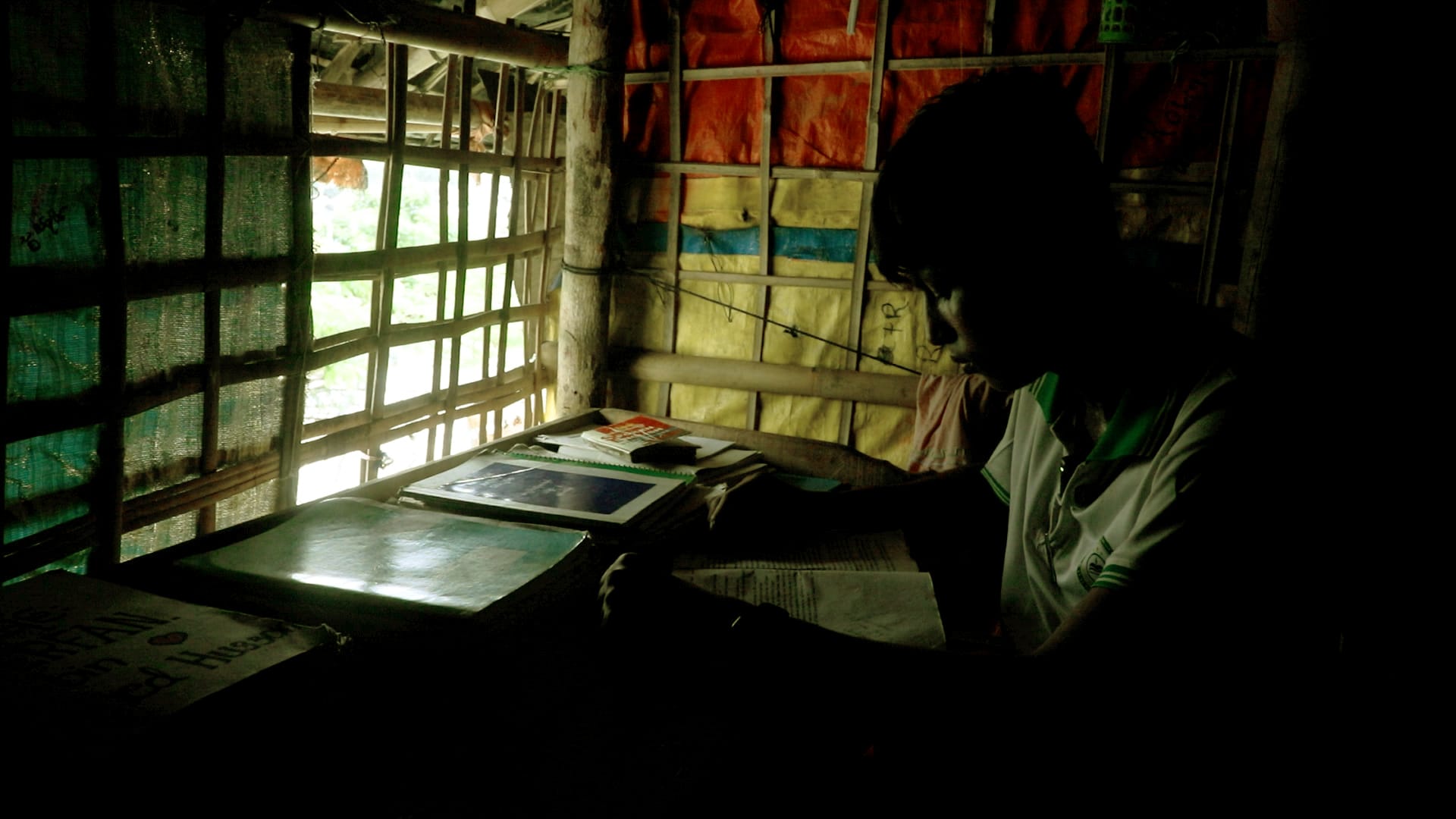

Ayrshad risked everything. He returned to Myanmar alone, leaving behind a semblance of safety in Bangladesh, only to take a shot at the exams. He could not attend a formal school but studied privately, preparing for matriculation.

Since this Rohingya man is not recognised as a citizen of Myanmar, he lacks the inherent right to sit for his board exams. Ayrshad faced immense bureaucratic hurdles. “Because I had no citizenship, I had to struggle a lot to fill out the forms, explain my long absence, and meet other requirements. I had to pay bribes to convince them.”

Yet, he passed matriculation in the academic year of 2022-2023 with distinctions in chemistry, biology, and physics. He was recognised as one of the top ten students in Rakhine in 2023. He achieved a total of 460 marks, exceeding the 450 required for MBBS admission.

Although these marks would have sufficed for any citizen of Myanmar to pursue a path in medicine, Ayrshad's Rohingya identity closed that door.

The Myanmar authorities initially offered him admission to University of Computer Science, Yangon instead. He completed all the paperwork – including obtaining a temporary transit paper allowing Ayrshad to travel between states without a national ID. But on the day he was set to leave for Yangon, violence erupted and the roads were blocked as a result of the ongoing conflict between the Myanmar military junta and the Arakan Army reaching a new height in October 2023.

In May 2024, he fled his birthplace again when the conflict worsened. Ayrshad returned to Bangladesh. But there is no policy in place for tertiary or higher education in the Rohingya camps, according to Mohammed Mizanur Rahman, Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner.

Ayrshad represents thousands of Rohingya youth whose right to education has been denied — first in Myanmar, and again in Bangladesh.

Ozi Ullah, a school teacher in Nayapara Registered Camp since 2004, was forced to leave school in Myanmar right before his matriculation exam in 1982, “The government in Myanmar did not allow us to study further because they feared we would begin advocating for our rights.”

Nasir Uddin, a professor of anthropology at University of Chattogram, explained how the prospects for the Rohingya community’s development have been steadily curtailed under authoritarianism and dominance in Myanmar since 1962, “What began as restrictions soon turned into systematic discouragement from higher education. Legal barriers were crafted to keep them out of universities, ensuring they could not pursue advanced studies. Over time, these measures not only blocked their path to education but also stifled their wider social and cultural growth.”

Ozi Ullah fled to Bangladesh during the 1991 operation by the Myanmar Army, seeking refuge and a new life.

His son, Mohammad Hossain Johar, was born in 2002 in the Nayapara Registered Camp. Johar attended the nearby Leda Government Primary School alongside Bangladeshi children and later Nheela High School, a semi-government institution.

But history repeated itself in 2019. Only months before his Secondary School Certificate (SSC) exams, Johar’s hopes were crushed, “The head teacher told me, ‘From today, you will not come to school. You are Rohingya.’ The day I was expelled, I cried all the way home. My friends asked why, but I could not explain.”

The school’s head teacher, Mohammad Abdus Salam, confirmed to Netra News that in 2019 about 15 to 20 Rohingya students were expelled following a government order. "Since then, we have not admitted any Rohingya students," he said.

Netra News obtained the letter. On January 28th 2019, Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC) Md Abul Kalam, following directives from the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Home Affairs, issued a circular instructing all schools, colleges, and madrasas in Ukhiya and Teknaf not to admit Rohingya children. The order also included lists of Rohingya students already enrolled in these institutions, directing authorities to immediately expel them and submit compliance reports. Furthermore, camp officials were instructed to keep the students under surveillance to ensure they did not leave the camps.

Since then, the doors of Bangladeshi educational institutions have remained closed to Rohingya children. "I dreamed of becoming a teacher, like my father, to educate my community," Johar added. Later, he attempted to enroll in other schools but was refused admission due to his Rohingya identity.

Now, he lives in a two-room house with his wife and their ten-month-old child in the camps and works as a volunteer in a livelihood program for an NGO. As a father himself, Johar is now worried about his child’s future, knowing the same educational barriers that thwarted the family’s dreams for two generations could very well await his own son or daughter.

Another Rohingya man born and raised in a Rohingya camp in Cox’s Bazar, knew the risks of seeking education. He studied in a nearby school in secret, using falsified documents.

He claimed that he was arrested from his school on February 11th 2019, for hiding his Rohingya identity. "They [the police] asked me various questions about who else was studying using fake identities. After four days in custody, they sent me to jail with a tree theft case. I secured bail after ten days.”

Undeterred, he carried on. “On November 1st, 2022, just five days before my Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) exam, my brother and I were detained again in Chattogram. That night, we were released only after a bribe of Taka 412,000 was paid,” he claimed.

Yet, he passed the HSC exam in flying colours and took university entrance exams for Dhaka University, Chittagong University, and Bangladesh University of Professionals.

“I ranked well in all of them," he said. Now, he is studying Media and Communication at Istanbul Ticaret University in Turkey under the Türkiye Bursları scholarship. "We never get true information in the camps or from Myanmar. I want to become a journalist to uncover the truth. I want to return to Myanmar one day and report objectively."

“Education is our only path to freedom.”

He was able to travel to Turkey after obtaining a fake Bangladeshi passport and other documents required of a Bangladeshi national.

Jamal Uddin, head teacher of Leda High School, a secondary school near the Rohingya camps in Teknaf, told Netra News, "Now, if anyone comes here to study, we follow the government directive requiring birth certificates, photographs, parents’ national ID cards, and the primary education completion certificate. Even so, if someone hides their information and manages to get admitted, we later verify it and remove them. We are bound to follow government orders."

Since June 1st, over 300,000 Rohingya children have been, facing further uncertainty in their education, as nearly 6,400 NGO-run informal schools in Cox’s Bazar camps have either shut down or reduced class hours sharply due to funding shortages.

"70% of education is covered by UNICEF. 30% is covered by other NGOs such as Save the Children and Educo; these organisations were operating in full swing. In UNICEF coverage areas, primary education has been shut down due to a funding shortage. UNICEF has laid off around 1,100 to 1,200 local teachers," said Mohammed Mizanur Rahman, Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner.

This creates a new layer of despair.

Azida, a student in Balukhali Camp 11, said, "I was in class three at Lily School. Now that the school is closed, I feel very lonely. We feel more unsettled and have to stay home all day. When the school was open, teachers taught us well, and I played with my friends."

Mohammad Erfan, a class four student, echoed her sentiments. "I’m starting to forget what the teacher taught us."

The consequence

A Rohingya man, now 26, lives in Balukhali camp with his four-year-old daughter, wife, and mother.

In 2017, he said he watched his father being murdered in front of his eyes in Myanmar, a moment that changed him forever.

He once dreamed of becoming a historian and documentary maker. He wanted to record the truth and show the world the atrocities his family suffered. He also wanted to show that the suffering of his community did not end with flight; rather, in his words, it continues every day inside the cramped camps.

However, the lack of access to education in Bangladesh crushed his hope, "I stopped studying after class six. One reason I quit was knowing that even if I reached class nine, I couldn’t go to college. I had no chance to become a doctor, teacher, or engineer."

After dropping out, he spent his days wandering the camp, chatting with friends, and gambling. This path led to large debts. To repay them, he and friends, who had also dropped out and were in debt, planned a kidnapping. After making some money that way, he quit, but later joined an armed group.

"If I had seen a brighter future, I would have continued my studies, and my life would not have turned out this way." His story reflects the harsh reality in the camps where blocked opportunities often push youth towards crime and dangerous migration routes.

Now, due to severe funding shortages, this crisis is worsening.

Mohammed Rofique (Khin Maung), one of the five rotating presidents of the Rohingya Camps, said, "Because our education levels are low, many people end up involved in harmful activities. A good education can help people avoid such fates."

Mohammed Rofique (Khin Maung) was one of the three moderators in the recent stakeholders meeting with Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus. "We lack people capable of making strategic decisions. So, we often take steps which are detrimental to the community because we do not have skilled policymakers. In the camps, there are very few who can develop a strong curriculum or write our own history for our children."

Despite the overwhelming odds, a few Rohingya have managed to continue their studies abroad and established themselves.

Maung Sawyeddollah, for instance, won a scholarship to New York University and obtained a US visa last year from the US embassy without a passport following a clearance from the Bangladesh government. From the United States, he actively campaigns for Rohingya rights, seeking justice for his people, "We have filed a case against Meta in Ireland and another in the United States because Meta was used as a tool to spread hate speech and misinformation."

"I am also focusing on new cases and witness accounts of human rights abuses and the brutal victimization by the Arakan Army in Rakhine. My main effort is to have the Arakan Army designated as a terrorist organisation in the US. I am meeting members of Congress, Senate staff and various State Department bureaus to push this forward."

Nasir Uddin, professor of anthropology at University of Chattogram, believes bringing Rohingya youths into mainstream education can help the nation avoid a lost generation. "Those who have completed SSC or college — coming from Rakhine or Arakan — face limited options. They cannot enroll in primary or high schools. Therefore, based on their level of education and category, an NGO-run schooling system can be arranged.”

Nasir suggested, for example, out of 34 camps, five could have high schools, and two or three could have colleges. “A curriculum can be designed for them. If the government ensures education under its policy framework, NGOs and INGOs can implement it effectively. This should be considered within Bangladesh’s policy framework for the Rohingya. Through such coordinated, combined efforts, it is possible to integrate Rohingya youth into mainstream higher education."

On February 12th 2025, the Supreme Court of India ruled that Rohingya children must not face discrimination in accessing education. The court declared, “No child shall be denied education — even if they are refugees.”

Meanwhile, for individuals like Ayrshad, hope persists. He now works as a teacher in a community-based school and has been pinning his hopes on distance learning. "I applied to the online University of the People, and they accepted me. Classes will start in September. Since becoming a doctor is out of the picture, I have now applied to study software engineering," Ayrshad added.

Mohammed Rofique (Khing Maung) concluded with a plea, "This country is not ours. We have taken refuge here, and we are very grateful to the Bangladesh government and its people. However, we have some fundamental rights. If these are not met, our generation will be lost. We do not demand anything more than this: the opportunity to study and go to universities."

When asked about the future, Mohammed Mizanur Rahman, Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner, replied, "I have not received any government policy so far that allows higher studies, tertiary education for Rohingyas.”●