The bridge that broke the river

In 1998, Bangladesh witnessed a milestone: the inauguration of the Jamuna Bridge. The 4.8-kilometer structure across the mighty Jamuna river fundamentally transformed connectivity between the northern districts and the capital. But projects of this scale often come with casualties.

The story begins in Charpoli, a riverside village in Tangail. Twice a week, on Sundays and Wednesdays, the local market comes alive. People gather, trade, and children fill the nearby school grounds. Buried beneath this apparent normalcy is the grief, loss, and anger of a community that has lost its lands to aggressive river erosion for decades.

“The city protection dam [guide bund — which are structures built to constrict the wide river in a narrow channel] was supposed to be upstream on the Sirajganj side, but it was moved toward us. That’s when our side began collapsing. The bridge should have been placed upstream, but it wasn’t — because this side was rural,” claimed seventy-year-old Hazrat Ali, pointing toward the Jamuna, which swallowed his homestead.

He believes that the towns were prioritised. “After the bridge was set downstream, our misery began.” Ali’s complaints are not emotional exaggeration, but rather rooted in geography and engineering.

Over the past 25 years, the guide bunds and structural interventions associated with the Jamuna bridge have caused irreversible changes to the river’s natural flow. Upstream, miles of permanent sandbars now obstruct the river, while downstream, entire villages, settlements, and farmlands have vanished into erosion.

Devouring of the river banks

Villagers Auwal Sheikh and Mokaddes Mia echo Ali’s sentiment. “Before the bridge, the river was four kilometers to the west. After the bridge, erosion drove us out. Everything vanished into the water,” said Auwal.

Standing beside a line of geobags, Mokaddes added, “Our house was on the other side. We crossed the river as it eroded everything. Now we live beside these geobags. A little more erosion and this will also be gone.”

Experts explain that the upstream embankments narrowed the river’s width, causing hydraulic pressure to increase sharply on the downstream, especially on the Tangail side. As a result, the river abandoned its natural path and began devouring the banks. This constant moving is a phenomenon scholars call "cyclic displacement."

Dr. Shafi Noor Islam, a professor at the Department of Geography, Environment and Development Studies at Universiti Brunei Darussalam, reveals the extent of this instability in his research on “char dwellers” — who are not confined to a single location, rather scattered across the river’s erratic geography, victims of the bridge's altered flow.

Upstream in Sirajganj, they inhabit the vast, new sandbars created where the bridge’s infrastructure slowed the river’s flow, essentially living atop a man-made sand desert. Downstream in Tangail, they are the displacement victims of the accelerated water pressure, forced to live on the precarious edges of eroding banks or on temporary islands formed by the debris of their former villages. Whether on the accumulating sands of the west bank or the dissolving soil of the east, these communities share a common legal limbo: inhabiting land that the river creates and destroys faster than the government can survey it.

Dr. Islam notes that “the frequency of displacement varies from 1 to 9 times due to river erosion” among the families surveyed for his research, and that 52% of the respondents — in one of his key studies, 102 households were surveyed, in another 130 — reported being displaced 7 to 8 times. This data highlights that for families like Mokaddes’, losing a home is not a singular event but a recurring life sentence.

Research by Syed Al Atahar, a PhD candidate at the Graduate School of Environmental Management at Nagoya Sangyo University, confirms the sheer scale of this impact. In his study on development-driven displacement, Atahar notes that “more than 7,000 acres of land were acquired for the bridge construction, affecting roughly 16,500 households with 100,000 people — directly (lost their physical assets) and indirectly (lost their livelihood from the project).”

While downstream residents face sleepless nights in fear of erosion, the picture upstream in Sirajganj is entirely different. There, the once-roaring Jamuna has shrunk into a barren sand desert. Even during the monsoon, water is scarce. The river has narrowed so drastically that vans and motorcycles now cross on small boats.

The “China Bandh,” once built to protect the Sirajganj town from floods, now stands almost useless — huge sandbars have risen right beside it, forming permanent land where crops are cultivated, and plots are leased out. Looking from the middle of the bridge, it is hard to tell whether this used to be a river or a vast field.

Residents claim the river began dying after the bridge was built. “Twenty-five years ago, our home eroded away. Now it’s just sand, no water,” lamented fifty-five-year-old Haran Ali. Nur Uddin, close to Haran’s age, added, “Four or five years after the bridge, chars began forming. Fishing is banned within six kilometers of the bridge, and I know of many fishermen who have abandoned the profession.”

A shifting map

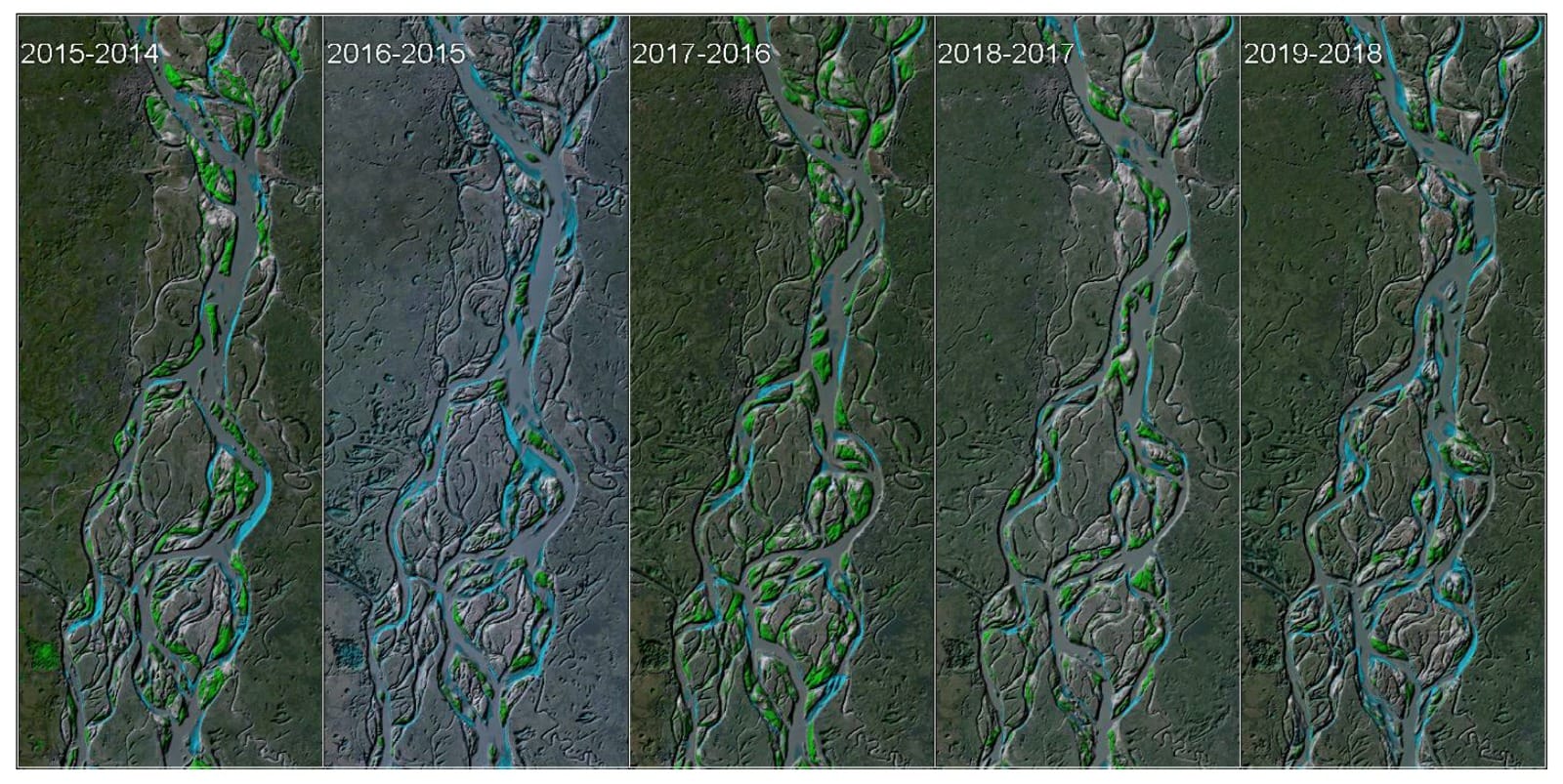

The visual evidence of this ecological upheaval is etched into the cartographic history of the region. Recent physical modeling provides stark proof of the river's volatility. A 2024 study led by A. K. M. Ashrafuzzaman of the Hydraulic Research Directorate at the River Research Institute analysed satellite imagery from 1984 and 2023 to track the river's behaviour.

The research found that the river’s left bank has undergone lateral migration of up to 5.3 kilometers in less than four decades. This relentless shift has resulted in the erosion of more than 100 square kilometers of land since 1984 in the Rowmari and Char Rajibpur upazilas alone, rendering thousands of people homeless.

Jamuna has historically always been a river that charted a new course year upon year.

According to Knut Oberhagemann, a specialist with Northwest Hydraulic Consultants in Canada, the Jamuna River corridor expanded relentlessly from the early 1970s until the early 2000s, driven by a massive "sediment slug" generated by the 1950 Great Assam Earthquake.

During the 1990s, erosion rates peaked at over 2,500 hectares per year, devouring floodplain land to create unstable char land. While the river historically braided (split and rejoined around temporary gravel/sediment bars, creating a “braided” pattern) naturally, structural interventions have altered these rhythms. The Independent Evaluation Department of the Asian Development Bank notes in its 2020 performance report that the river is capable of shifting its course by more than 300 meters in a single year due to the imbalance between sediment transport capacity and sediment supply.

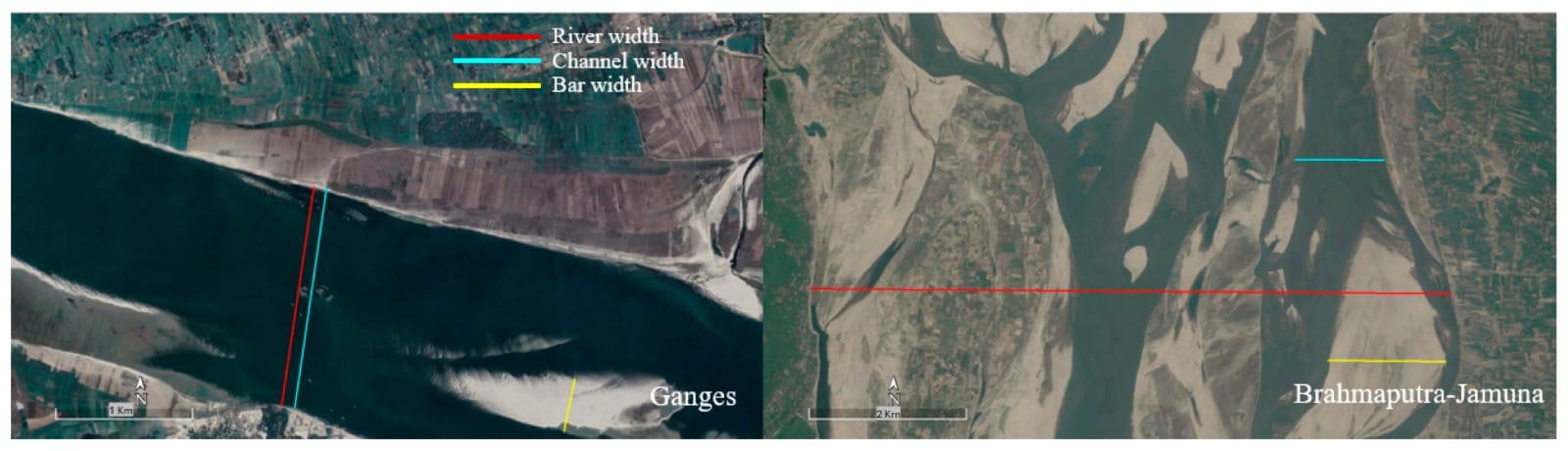

However, the construction of the bridge imposed a rigid constriction on this highly dynamic river. River management specialist Oberhagemann observed, with others, in his work that immediately after the construction of the Jamuna Bridge and its river training works, the “braiding index” of the downstream reach reduced drastically.

Naturally, the Jamuna acts like an untamed rope, frayed into dozens of small, shifting channels that weave around islands. This chaotic structure, known to engineers as a high braiding index, allows the river to carry its massive load of sand and water safely. However, the construction of the Jamuna Bridge forced this wide, messy river into a 'straightjacket' — a single, narrow channel. According to the book Living on the Edge: Char Dwellers in Bangladesh, edited by Mohammad Zaman and Mustafa Alam, this artificial narrowing created a bottleneck.

Upstream, the water slowed down and dropped millions of tons of sand, choking the riverbed. Downstream, the water shot out of the constriction with firehose-like pressure, blasting away the riverbanks of Tangail and devouring villages in its path.

While this effectively stabilised the river downstream, it came at the cost of natural flow upstream, contributing to the formation of permanent sandbars and altering the hydraulic pressure that exacerbates erosion on the banks. The satellite data confirms an overall widening trend over the last four decades due to this increased braiding intensity, leading to widespread bank erosion in the project area.

This shrinking is not just a cartographic change—it has directly worsened flooding patterns and reduced navigability.

‘Jamuna River cannot be controlled’

Environmental activist Sabnat Lahoree, who has studied the Jamuna for years, says the seeds of disaster were sown at the very planning stage. He notes that foreign experts had warned of potential risks, but their advice went unheeded.

“There is no such thing as ‘river control’. Six experts came from countries like the Netherlands and Denmark. They said this river cannot be controlled; it must be allowed to behave naturally. But instead, they built a permanent upstream embankment and none downstream. The river lost its balance,” said Lahoree.

He added, “People protested illegal dredging. Geobags and ‘routine’ river training have destroyed natural ecology. One side is full of sandbars, and the other side is full of erosion. This has torn apart social bonds between communities on both sides of the river.”

While newly formed chars have expanded agricultural land upstream, the success is fragile. According to the agriculture department, cultivation of chili, maize, onions, garlic, and peanuts has increased significantly in 2025. Maize production alone has grown by 65%. Yet these chars are highly unstable — annual monsoon floods destroy 30–35% of crops.

More alarming is the crisis in fisheries. According to the book Living on the Edge, the river's ecosystem is in steep decline. Research within the volume, such as the study on coastal livelihoods by Harvey Demaine, confirms that the catch per unit effort in wild fisheries is steadily dropping. Parallel reports indicate that Hilsa breeding has declined by 40%, while Boal and Ayer populations have seen a 35% decrease.

Consequently, around 4,000 fishing families are now at risk of losing their livelihoods, while boatmen lose work as the river dries and chars replace waterways.

World Bank inspection panel confirms major irregularities

Rehabilitation remains one of the most painful chapters of the Jamuna Bridge project. Despite international financing, the process violated several standards. Jonathan A. Fox, a professor of social sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz, analysed the World Bank's inspection reports. He highlighted severe negligence, noting that out of a total of 2,166 families officially recognised as affected, only 450 received proper rehabilitation. Ultimately, 79% of affected families were denied compensation.

Worse still, the compensation process was riddled with systematic corruption. As noted in Syed Al Atahar's study, “most respondents said they paid 10 to 15% of their compensation money as bribes at different stages of government processes to obtain their compensation money.” Furthermore, the complex land registration system created a legal trap; many char dwellers possess land through inheritance but lack legal documents, forcing them to rely on middlemen or land office officials who often exploit their illiteracy.

Meanwhile, authorities continue “cosmetic” erosion control with geobags under the ADB-funded Flood and Riverbank Erosion Risk Management Program. But char dwellers dismiss these as superficial measures. The 2023 Bangladesh Bridge Authority report states that dredging done between 2010–16 quickly silted up because of poor maintenance.

Who will save the river?

River researchers emphasise that Bangladesh must adopt an Integrated River Management approach. Professor A.S.M. Saifullah of Mawlana Bhashani Science and Technology University warns, “Giving separate upstream and downstream embankments kills the river. Eventually, the river dries up — exactly what we are seeing. If interventions continue, the impact will be catastrophic. Even the Padma Bridge will one day stand over dry land.”

He adds, “Bangladesh was created by rivers carrying sediment over thousands of years. If we ignore this reality, the environmental foundation of the country will collapse.”

The Jamuna Bridge, planned in the 1980s and approved in 1994, was built at a cost of $962 million with financing from the World Bank, ADB, and JICA. Yet researchers now argue that its environmental impact assessment failed to capture long-term hydrological impacts — an oversight now painfully clear.●