The Rohingya know where home is

A visual storyteller built a project which archives shreds of memory and identity of the Rohingya in one common space from across the world and generations; and tells the story about the life of a community rather than the destruction of it.

Every month, Mashruk Ahmed will curate an instalment of a photo-story series that questions established power discourse, featuring photographers who explore gaps, absences, and silences in Bangladesh’s socio-political records.

In this fifth edition, we feature an award-winning documentary photographer, author and visual journalist, Greg Constantine and his groundbreaking research project, "Ek Khaale – Once Upon A Time". Through rare photographs, family archives, letters, illustrations, and historical documents collected from the Rohingya in the camps and the diaspora, this project seeks to preserve the memory and identity of the Rohingya people. It not only challenges the dominant historical accounts long shaped by Burmese regimes by revealing a rich history spanning decades but also contributes an essential voice to the broader story of the Bangladesh–Myanmar borderlands — a narrative that remains complex and often underrepresented. You can find the fourth edition, “Awakening,” here.

2017 wasn’t necessarily ‘the genocide’. Yes, it was a catastrophic moment of mass violence, death, destruction and displacement of the Rohingya people in Burma, leading to their most recent largest exodus to Bangladesh, but the genocide against this community has been a process spanning decades.

I had already spent 11 years photographing the community by the time August 2017 happened. For me, it was something that was years in the making.

In early 2006, I made my first trip to southern Bangladesh to start a photo essay on the Rohingya. Ever since, I kept coming back. I had also spent time inside Rakhine State and then returned to Bangladesh after 2017. Up to 2020, much of my work attempted to record and investigate the violence perpetrated against the Rohingya and its impacts on them. This could be any form of violence, from the physical to the invisible/administrative violence carried out by the Burmese military and government. I have always felt the historical narrative — primarily manufactured by the Burmese authorities and others in Rakhine State — that the Rohingya are a group of foreigners who have never belonged or have no ‘history’ in Burma served as a motivating factor behind this violence.

Strip away the human characteristics and their history, spread hate about them, convince people this community is a threat — these are strategic tactics to dehumanise a people and, in the process, normalise the dehumanisation. In turn, others no longer see the Rohingya as a people.

At the same time, the visual narrative of the Rohingya is very much rooted in the ‘violence’ perpetrated against them. The death, the desperation, the lack of agency, the hopelessness — all of it is almost entirely focused on victimhood. While these characteristics are sadly a part of the Rohingya story, but, after all of these years, I realised these characteristics became the entirety of their identity. My work also contributed to this victimhood narrative.

However, I have also come to learn about the Rohingya and their place and history in Arakan and the contributions they have made to Burma — all of which contradicts the Rohingya’s portrayal to people in Burma and the world. I wanted to work on a project that required a radical shift, a project that would use the visual as a way to challenge both the historical narrative about the Rohingya and the visual representation of the Rohingya.

The whole project started with an instinct and curiosity, “I wonder what kind of visual materials exist out there that might tell a different story?.” In late 2020, I started reaching out to a few Rohingya in the diaspora, and the materials they shared with me confirmed my instinct — that was the start of “Ek Khaale” five years ago.

Building Ek Khaale

Having already worked with and knowing Rohingya around the world for over a decade, existing relationships built on mutual respect allowed me to expand my network within the community. I have been to camps in Bangladesh over 15 times since 2006, but this project would not have been possible without the efforts of Rohingya.

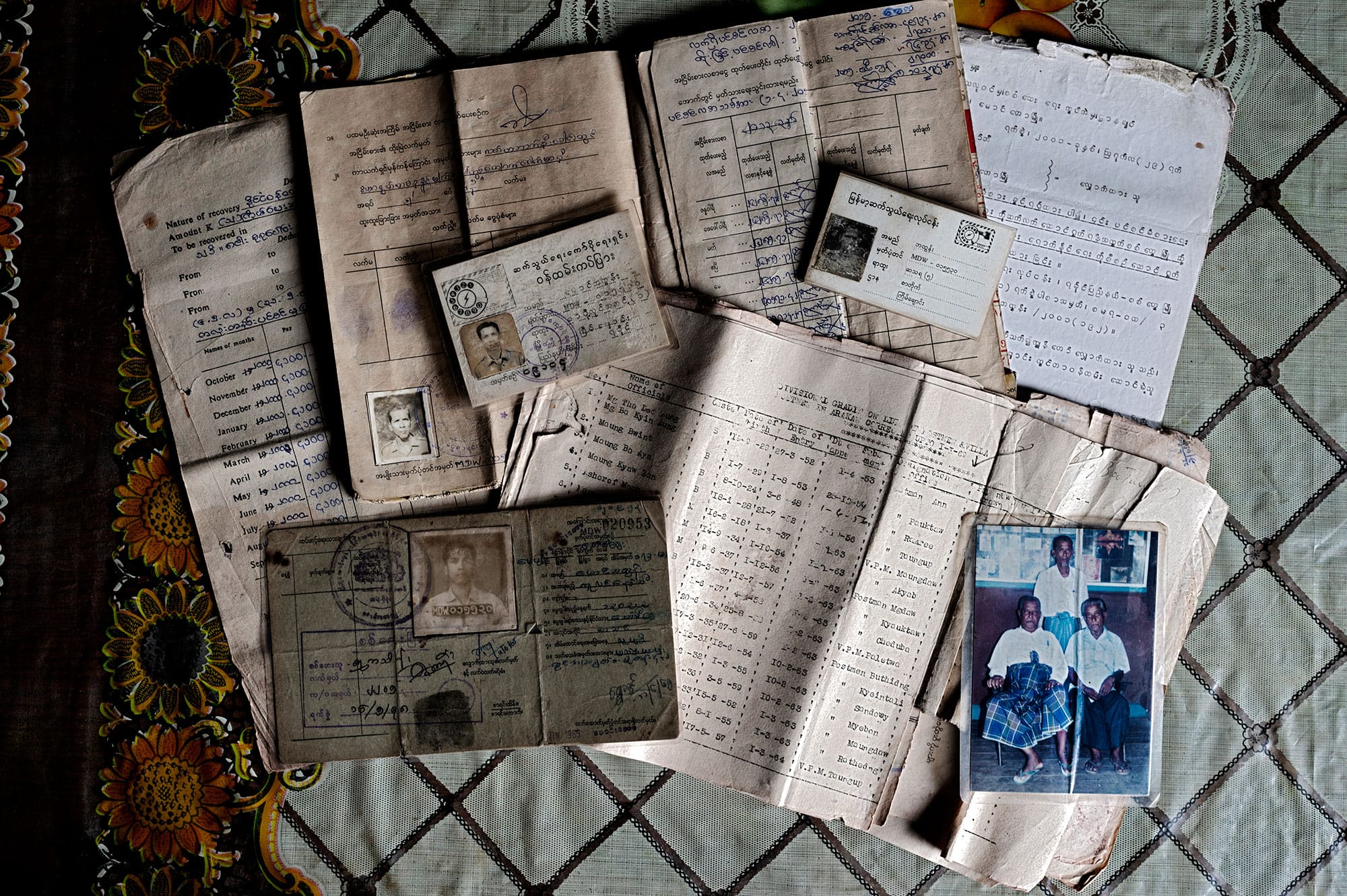

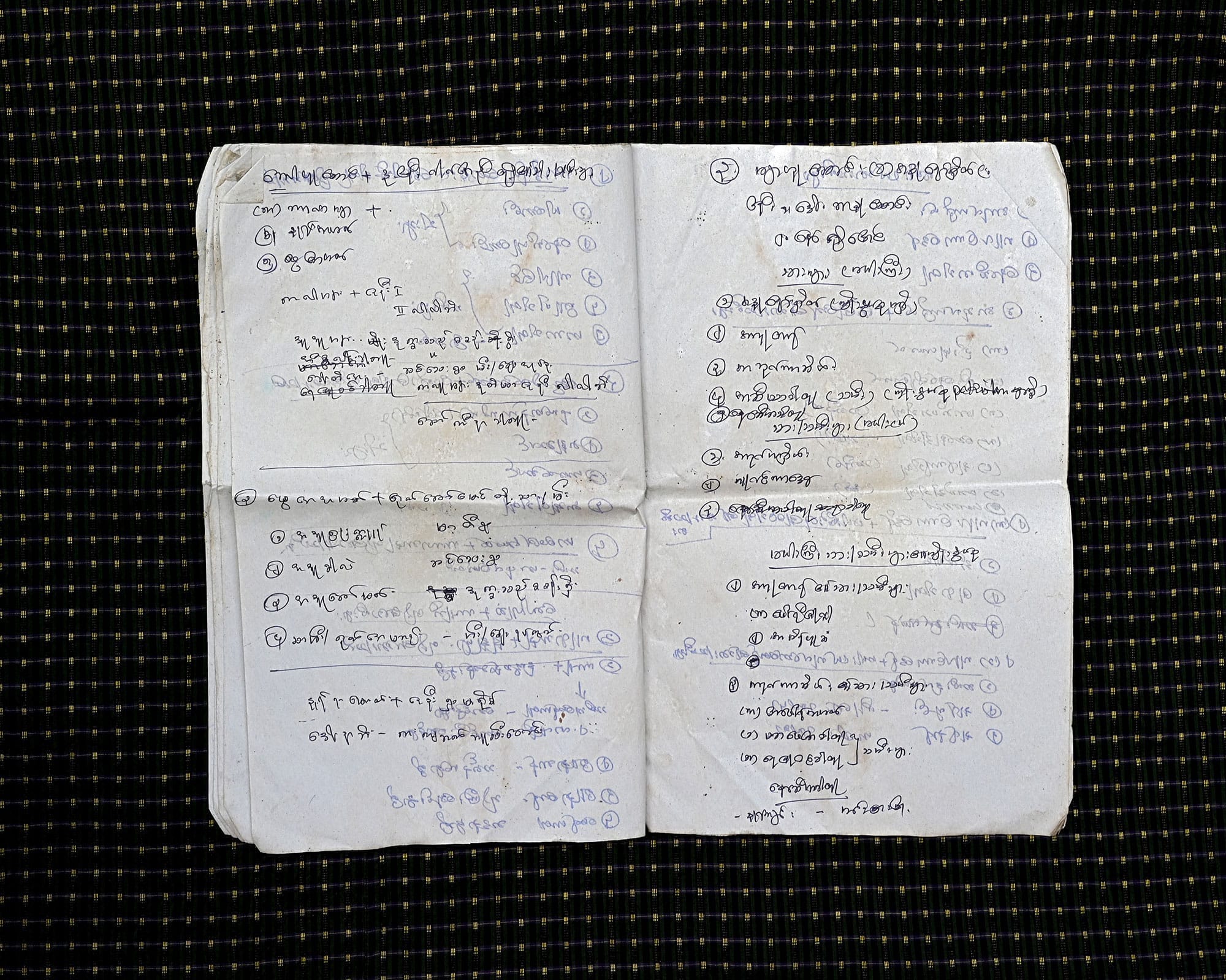

I worked with small teams of Rohingya youth (men and women) in the camps as well as Rohingya still living inside Rakhine State. They worked as the archival team. They spent months going out into the community, telling people about this project and asking people to show them old documents, IDs, photos, etc. They worked on the front lines in finding many of the Rohingya-contributed materials for the project. This then led to Rohingya elders getting excited about the project.

The trust, to a large extent, was already there, but being a neutral outsider worked in the project’s favour. Every community has its internal suspicions, internal distrusts, family feuds, etc. The Rohingya community is no different. But as an outsider, it became clear, the Rohingya were comfortable sharing materials with me that they may not have been comfortable sharing only with someone else from within their own community. This produced another layer of materials that were contributed to the project.

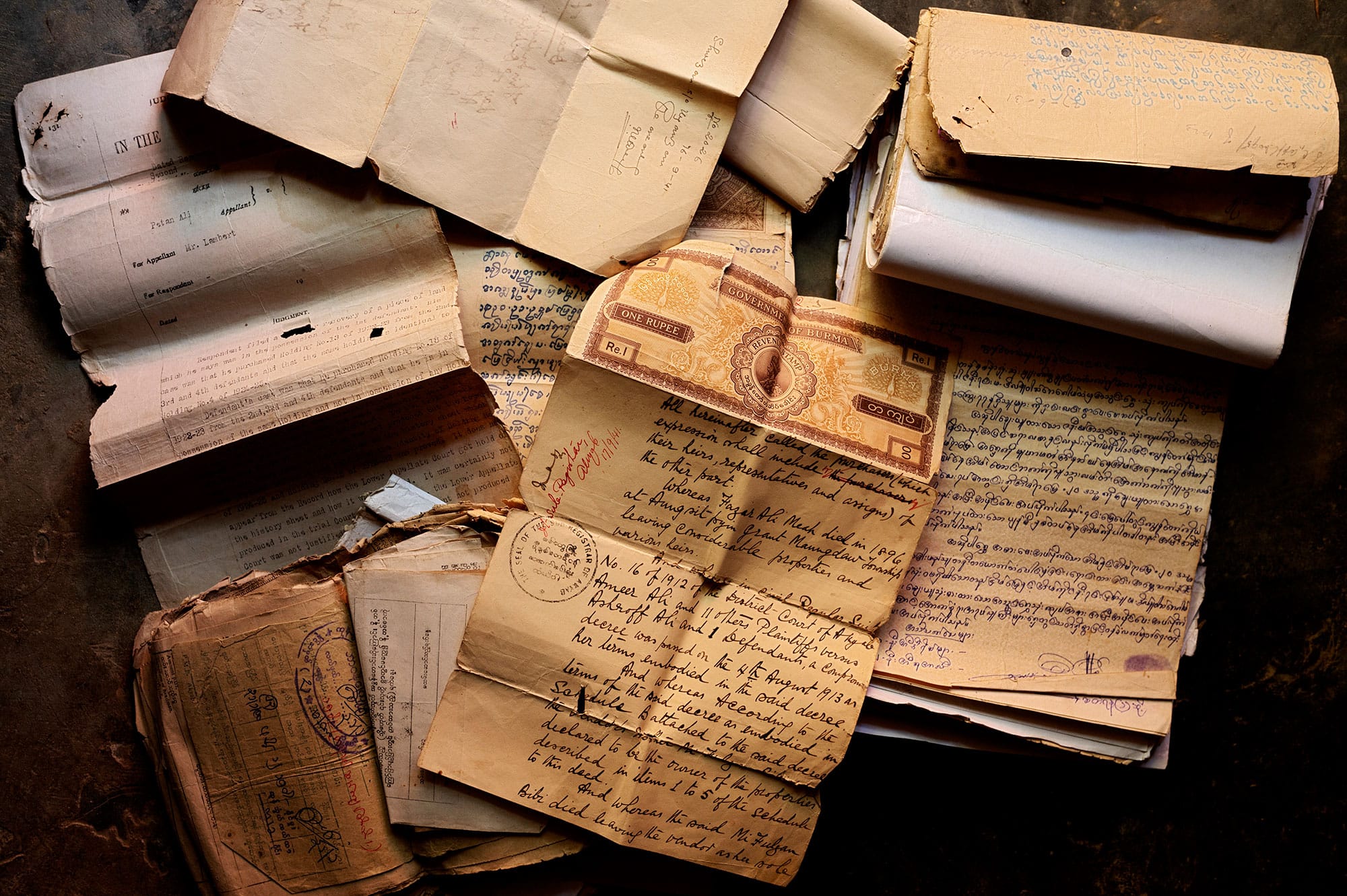

Another important aspect is that most of the Rohingya we met had never shared these documents or materials with anyone. Imagine, during the most unimaginable violence in 2017 — villages burning, homes being destroyed, people being killed everywhere — for a Rohingya to consciously make the decision that in addition to your children and family members to also grab the plastic bag that had been hidden in their house in Maungdaw or Buthidaung and carry it all the way to Bangladesh.

The Rohingya knew the incredible value of these materials. They knew that the minute these materials perished, was the minute they had no proof or evidence of their family history or their historical legacy in Arakan and Burma. And I was absolutely stunned when they told me that they had never shared these materials with people. But their explanation was very simple: No one had ever asked to see these materials before.

After about three years of working on the project, (this includes the Rohingya archival team members finding a trove of materials and the completion of my one-year fellowship in the United Kingdom allowing me to spend months and months working in a variety of archives), it was time to start analysing what we had in hand.

My approach was to permit the materials to shape the narrative of the project; and soon patterns started to form, narratives started to take shape and chapters, like in a book, started to organically develop. The materials found in various archives started to intersect with materials the Rohingya had contributed to the project. Gradually, the project’s nine chapters came to life.

I worked with Rohingya elders and turned to others who were very familiar with the Rohingya story (journalists, academics, historians) and I trusted them to be the ‘editorial’ advisors. They played a pivotal role in keeping the text in each chapter balanced, focused and historically accurate. While the text is there to provide context to what is ‘shown’, the visual materials propel the project’s narrative forward.

I spent almost a year working with all the visual materials, letting them drive the story. And during this time, I spent months playing with design techniques for how to translate all of this into a design — all that developed into the Ek Khaale website.

History, identity and genocide

Over the course of the project, it became very clear to me that just like every other community in Burma, the Rohingya community had active participants in Burma’s history.

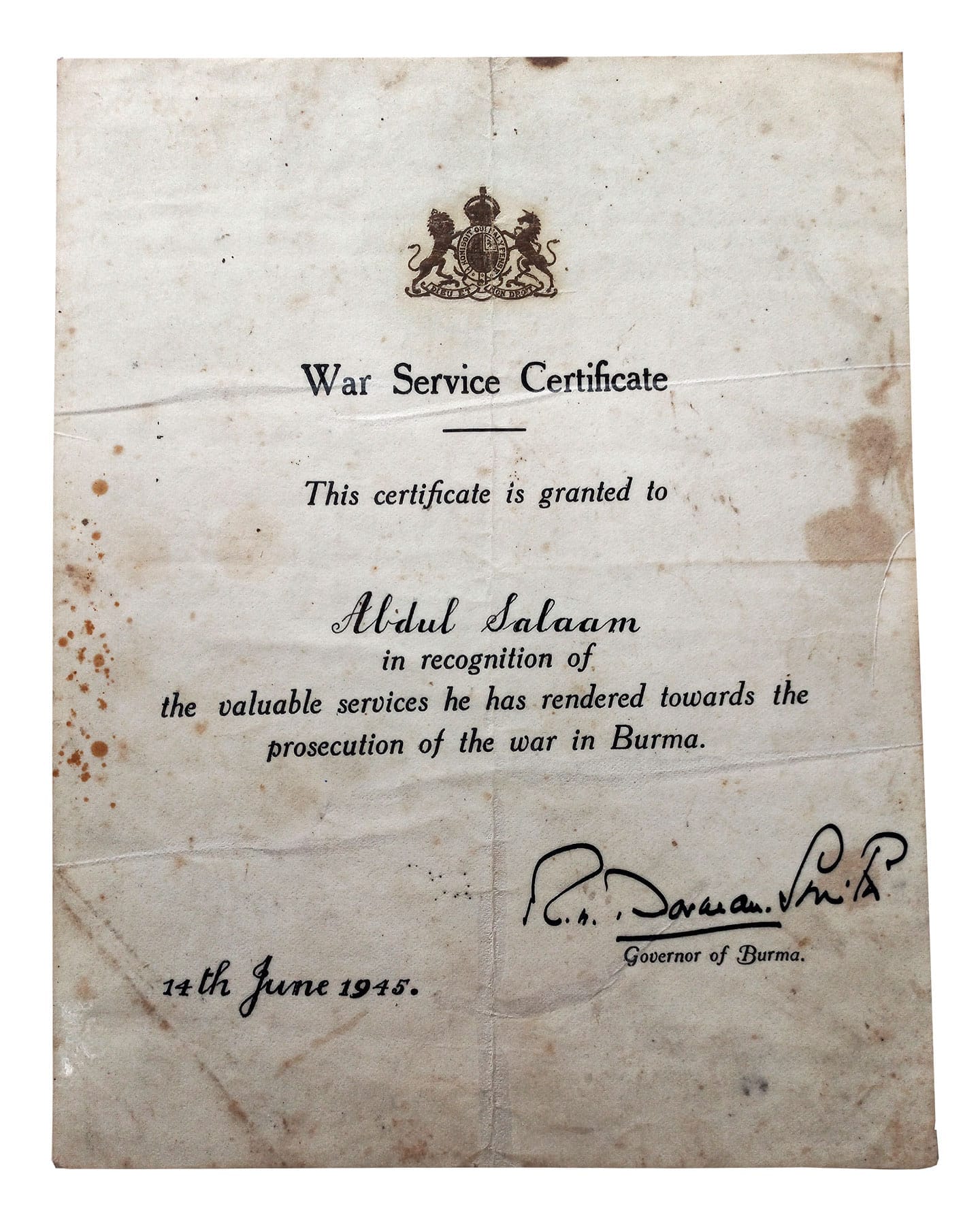

The Rohingya played a role in developing Burma’s educational system and in pushing back on the British systems that had been put in place. Like so many other ethnic communities in Burma’s borderlands, the Rohingya also contributed to the war efforts in World War II that led to the liberation of Burma from the Japanese.

Time and time again, Rohingya used their voice as a collective community to protest against being labeled as ‘foreigners’ — demanding recognition as people from Burma. Rohingya were politically active and, just like all other communities, the Rohingya had no choice but to also engage in armed resistance. Rohingya were there demonstrating in the streets of Yanong and Sittwe shoulder to shoulder with others during 1988. These are historical contributions that have been almost totally erased.

Decade after decade, the Rohingya consistently made decisions to preserve and fortify the position of their community within the growing antagonistic dynamics that materialised not only in wider Burma but also within Rakhine State. All of these actions, when placed in a timeline of history, show a community that has a deep sense of belonging exclusively to Arakan and Burma.

The Rohingya know where they are from, know where home is and have spent decades demanding (by themselves and in solidarity with others) a better place to live than the one offered by the oppressive Burmese regimes for the past 60 years.

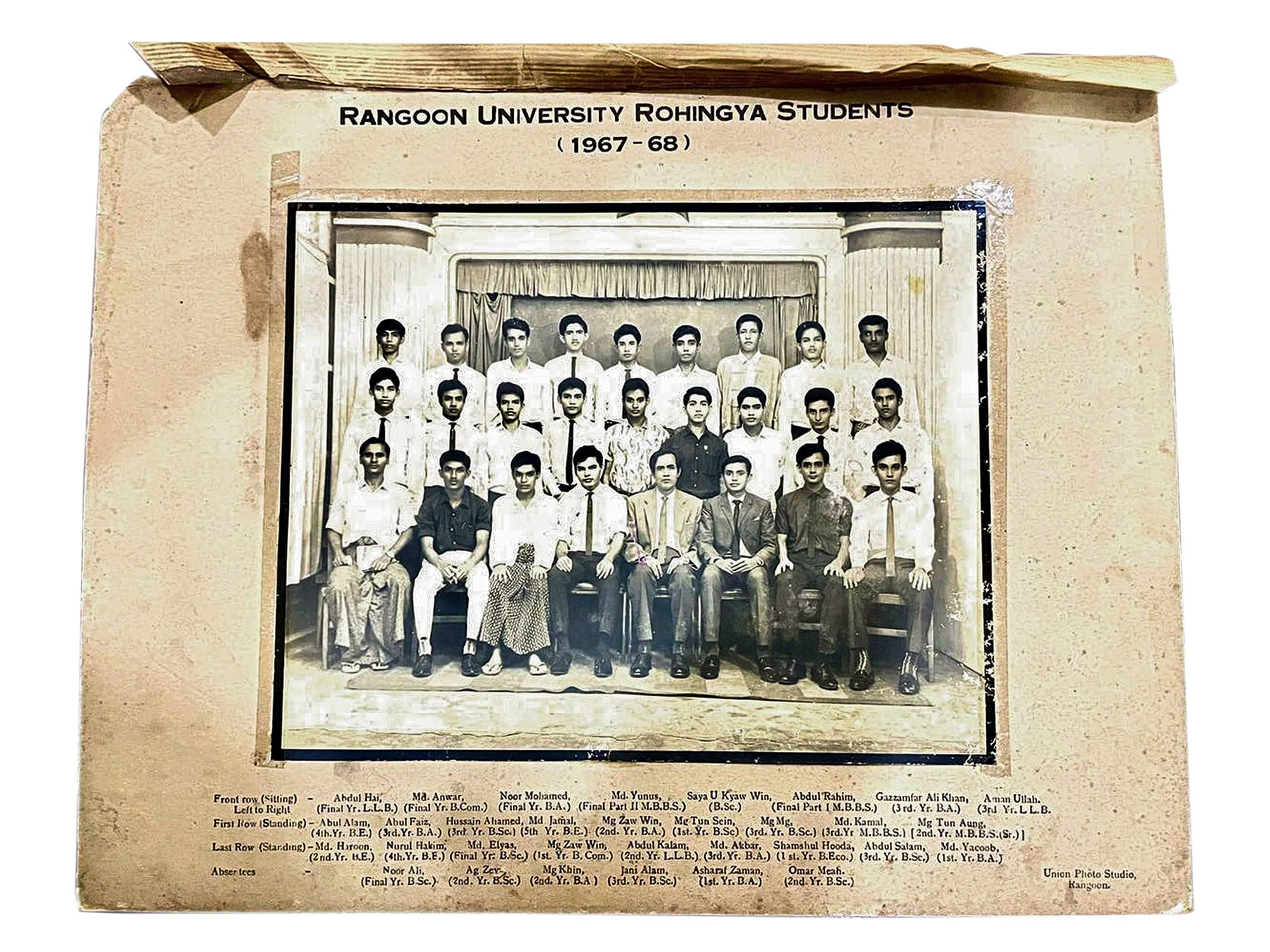

Besides all the physical violence perpetrated against the Rohingya, one has to also understand and acknowledge the role of the administrative and structural violence in the Rohingya’s persecution. For instance, the passing of laws and local orders, all of which degraded the Rohingya’s legal status or the community’s ability to function economically or politically within Burma. Then there is the arbitrary seizure of land, the inability to travel freely, to obtain higher education, hold jobs, have access to healthcare, and beyond — much of which never made the news headlines but successfully contributed to creating an ecosystem where the Rohingya became more and more vulnerable. At the same time, the destruction of materials of documentary heritage diminished the community’s ability to share its identity, history and memories with others and those within the community.

While we always define genocide as the physical destruction of a people (death and slaughter), for many Rohingya I have met over the years, they would say, isn’t the erasure or destruction of a people’s history and those things that attest to who they are, what their place was in society at a point in time, their representation of their collective identity — isn’t that a component of the genocidal process as well?

I would agree with them. And I feel this project in some kind of way, disrupts our definitions of genocide. It asks us to expand the way we see and think about genocide beyond just the physicality of this atrocity.

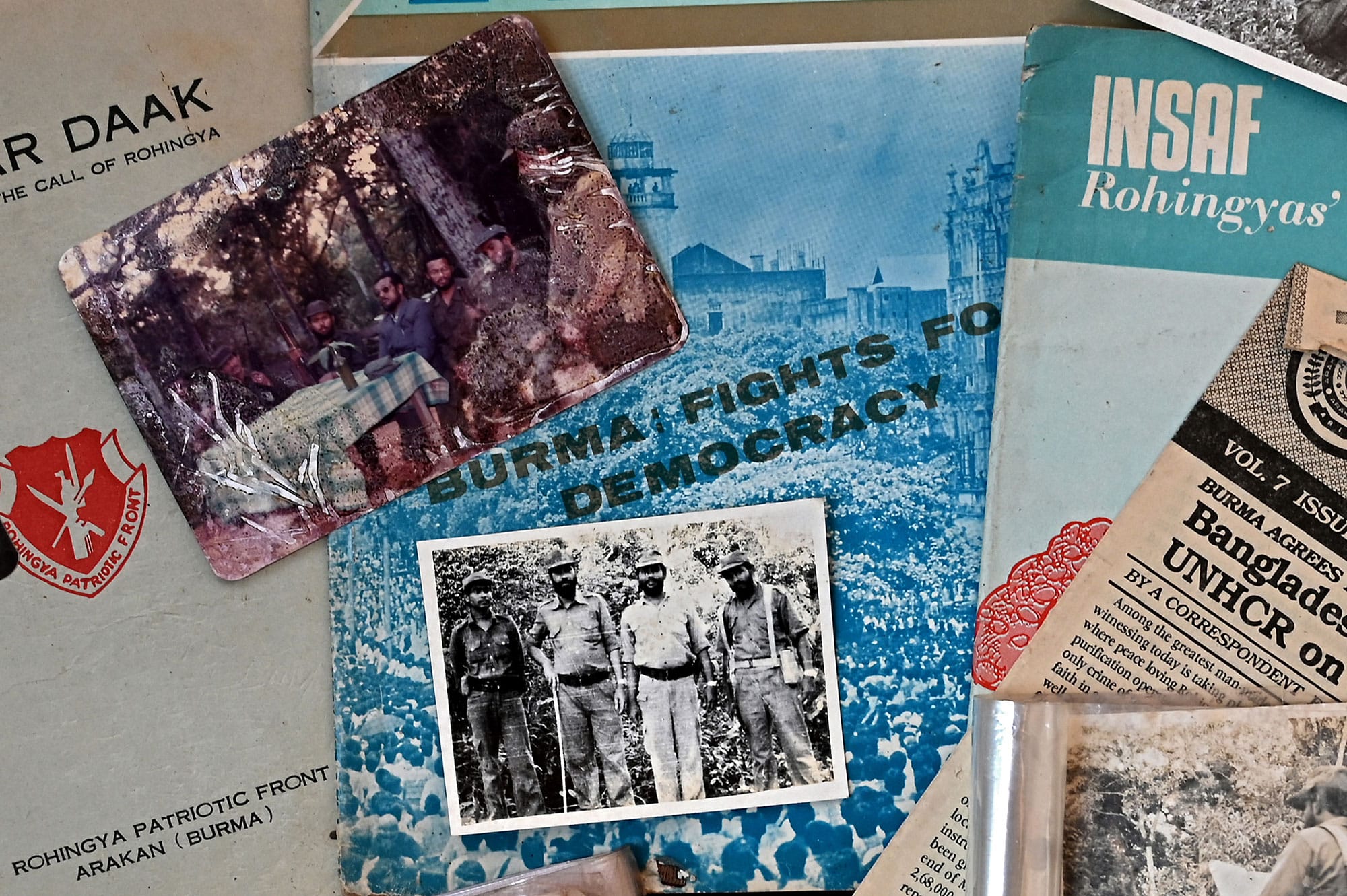

Politics, war and resistance

Books have been written about Burma history, Arakan history and Rohingya history, but almost no attempt has been made to ‘show’ this history. Ek Khaale does not claim to serve as a vehicle for being an authoritative history about the Rohingya, however, what it does attempt to do is use visual materials (sourced and cited) to show a history and a portrait of this community that no one has seen before. It uses these materials to place the Rohingya community as active participants in history rather than passive bystanders. It uses these materials to show the community’s deep connection to Arakan and to Burma in a way that challenges the manufactured narratives that over the years have unfortunately become accepted by so many people in Burma.

I think the visual materials that tell the stories of Rohingya’s role in WWII and resistance movements communicate something incredibly powerful — the Rohingya were just like other communities in Burma. Like the Karen, the Chin, Kachin and other communities, the Rohingya too wanted to see their country liberated from British occupation, and more specifically, the Japanese. To make this happen, they had to make decisions on who to align themselves with. Like the Karen, Chin, Kachin and other borderland communities, they aligned themselves with the Allied Forces (the British); and so the Rohingya were acting in a process of solidarity with others. No one can deny each of these communities (including the Rohingya) had their own self-serving motivations as well. Still, the Rohingya were part of this larger effort that contributed not only to Burma history but played a part in world history too.

This spills over into the history of armed resistance movements across Burma from the 1950s to present day. Every community in Burma has a history of taking measures through parliament to raise their voice, stake their claim and protect their own interests. And every community, including the Rohingya, has also taken measures through the jungle and armed resistance to accomplish what political tactics could not achieve.

Having spent well over a decade documenting stateless communities around the world, one can definitely see shared characteristics between the Rohingya and other persecuted groups. A dominant community rejects the identity of another and employs strategic measures (including ‘othering,’ laws, persecution, violence, dehumanisation, and more) pushing the unwanted community to the margins. After a period of time, this becomes accepted by the general citizenry and the exclusion then becomes entrenched and this then often spans decades and generations — this then fractures a community, shatters it.

The Dominican Republic, Kuwait, Kenya, Ivory Coast, even the history of the Bihari community in Bangladesh — all of these are examples that share characteristics of what’s happened to the Rohingya. Yet, one other parallel is that when you ask stateless people where their home is, they all know exactly where that place is. It is not that stateless people do not have a home, it is that the oppressive regimes in the places they call home have removed these communities by weaponising their connection to home (citizenship, opportunity, access to rights, political participation, etc).

Geography and borderlands

Rohingya have fled Burma and scattered all over the world. The dispersal of the Rohingya around the globe has been an ongoing process, as a result of persecution, since the 1950s. And with each wave of displacement or with each individual fleeing Arakan, those pieces of visual history in the possession of Rohingya have too been displaced from a centralized location, from the place where Rohingya call home, Arakan.

I think this has made it even more difficult for the Rohingya to contest these labels of foreignness that have been imposed upon them. So, Ek Khaale is part of a process of almost repatriating these dislocated shreds of memory and shared collective identity back into one common space. Like small pieces of a mosaic, each shred tells a small story, but when you place hundreds of them together, they create a portrait of the Rohingya and their history that most people have never seen before…or that was never presented in this manner.

Ek Khaale is part of a much larger process of restoration, of reclamation and of re-imagination that I feel the Rohingya community is going through and that other people in Burma need to go through as well.

Throughout the project, Rohingya voices have played an integral role. They did not only guide the project but have also provided additional layers of storytelling. The project consists mostly of documents, old photographs, paperwork, etc. — all of these materials, when put together, tell the collective story of a community.

Additionally, these visual materials come from multiple generations of Rohingya; and this aspect is one of the unique and incredibly powerful accomplishments of Ek Khaale.

Photography and personal journey

If I speak specifically about the 20 years of work I have done on the Rohingya, the project Ek Khaale builds on this previous work but it also is a radical departure from it. As a photographer, I aim to share stories through images. And that doesn’t necessarily mean those images need to be my own images, this is what I have learned from this project.

With Ek Khaale, I’m still a visual storyteller but we are utilising the photographs of others to tell this story. That is the only way this story could be told. And the story that is told is about the life of a community rather than the destruction of it. My previous work on the Rohingya was focused primarily on documenting the abuse, persecution and in many ways, the destruction of the Rohingya. However, Ek Khaale is very different.

It is not possible for me or any of us to sit and have a conversation with Rohingya who were alive during the 1920s, 30s and 40s, in those years leading up to Burma’s Independence and in the time during and after the creation of this new country. But one of many gifts an archive gives is awakening the voice from the past and something they spoke or something they did that has long been forgotten and placing it in the present, right here, right now. And in so many ways, what people see in an archive has the ability to re-establish a history that has been forgotten or correct and re-align a history that has been falsified and accepted by the majority as being true.

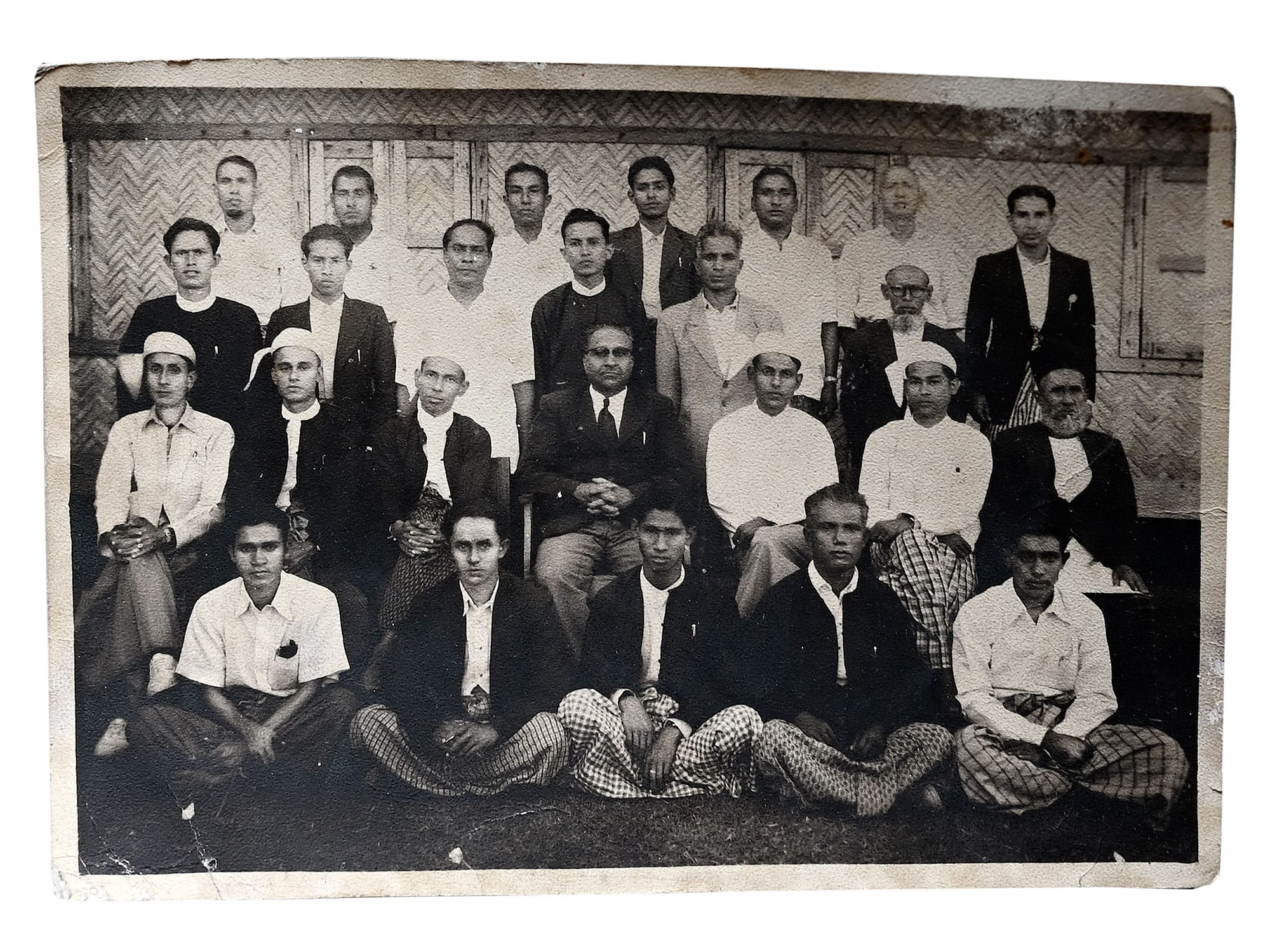

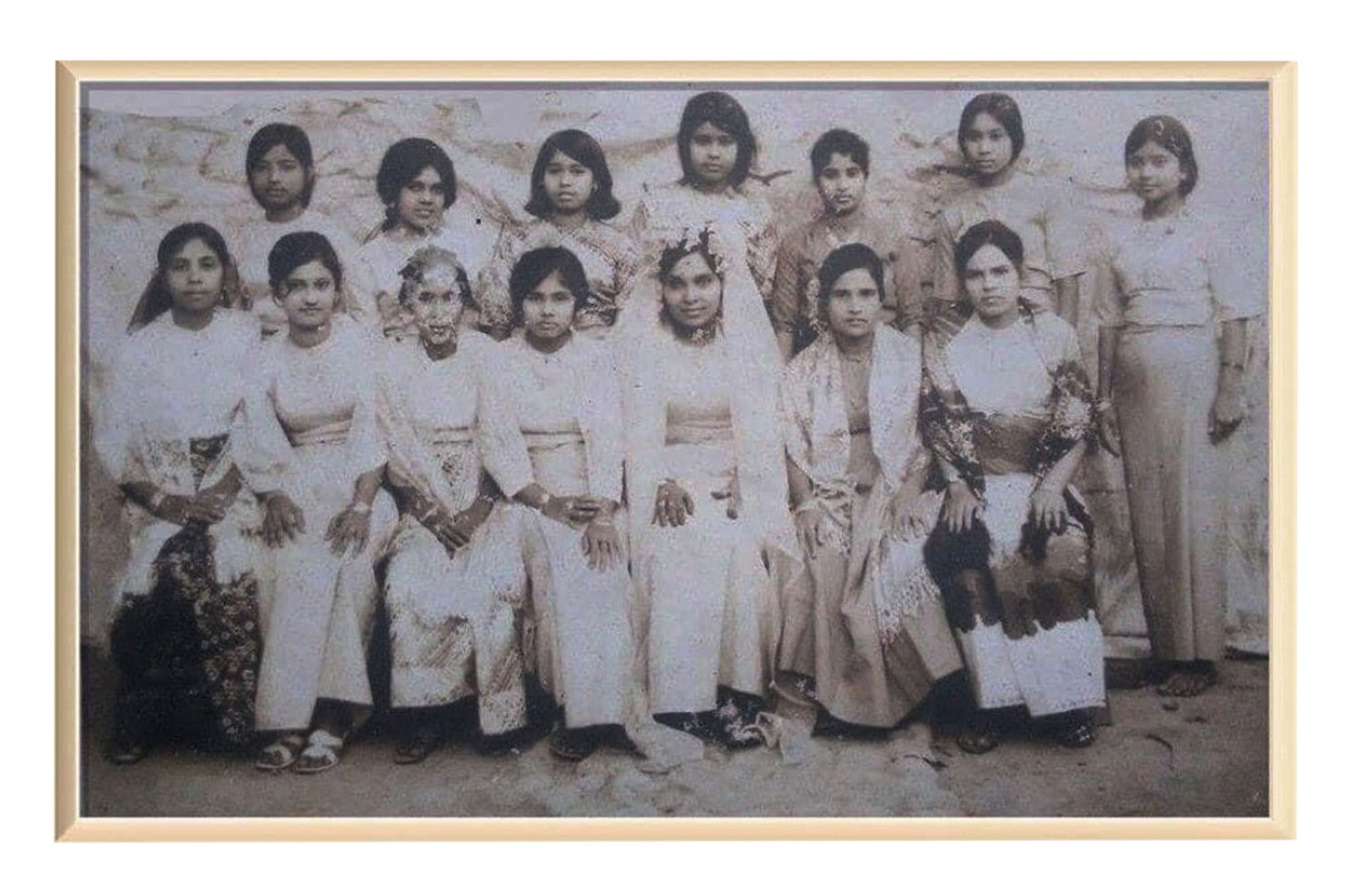

All of these materials synthesised together, collectively in a process (that I believe) is a restoration, is a rewinding of the visual representation of the Rohingya. We all have old photographs of family. The Rohingya’s old family photographs, contributed to this project, ask us to see ourselves in these photos. They ask others from Burma to see themselves in those photographs. And they ask us to see the Rohingya for who they were during those times in the 1950s and 1960s — they were government workers, students, and members of parliament. They were ordinary mothers, fathers, grandparents, uncles, aunts, neighbors, etc. Some were middle income families. “They look just like we do” — that’s one of the most powerful things archives can contribute.

Impact and future

The Rohingya have a long, deep connection to the place they call home, and that is Arakan and the country they belong to, Myanmar. The Rohingya were active participants in Burma’s history, not passive bystanders. And that from one generation to the next, the Rohingya have consistently stood in solidarity with others in the country to resist an increasingly oppressive government. Ek Khaale serves as a platform for showing a story where people can see and understand the Rohingya differently — I hope Ek Khaale’s first time visitors take this away from this project.

A lot of younger Rohingya have heard stories about their community, but a visual translation of this collective story has never really existed. What does a Rohingya lawyer, doctor or engineer look like? What does the Rohingya community look like when the community possesses a confidence that comes as a result of acceptance, citizenship, education, choice, safety, security, the ability to dream of a future and actually take the steps to achieve that future?

I feel these visuals have been absent for many young Rohingya. So, this project (which has been created by the active contributions from Rohingya themselves) serves as a way to reconnect them with their past, to visually confirm the stories they have been told by their parents or grandparents. It reconstructs what this community had at a period of time before everything went so terribly wrong and also for young people it resituates their community back into the larger fabric of Burma society.

Rather than seeing themselves as the ‘outsider’, the ‘banished’, it gives them the opportunity to see their community ‘within’ and ‘among’ the larger family of communities of Burma. I feel this can facilitate a renewed and heightened sense of belonging and confidence. It has been incredibly rewarding to see how young Rohingya around the world have responded to this project.

I hope Ek Khaale continues to grow with contributions from the Rohingya community across generations and the world, and that it expands as an evolving archive. Moreover, I want to do everything I can to see that Rohingya themselves are the ones managing this process.●