Vandals are “a pressure group”

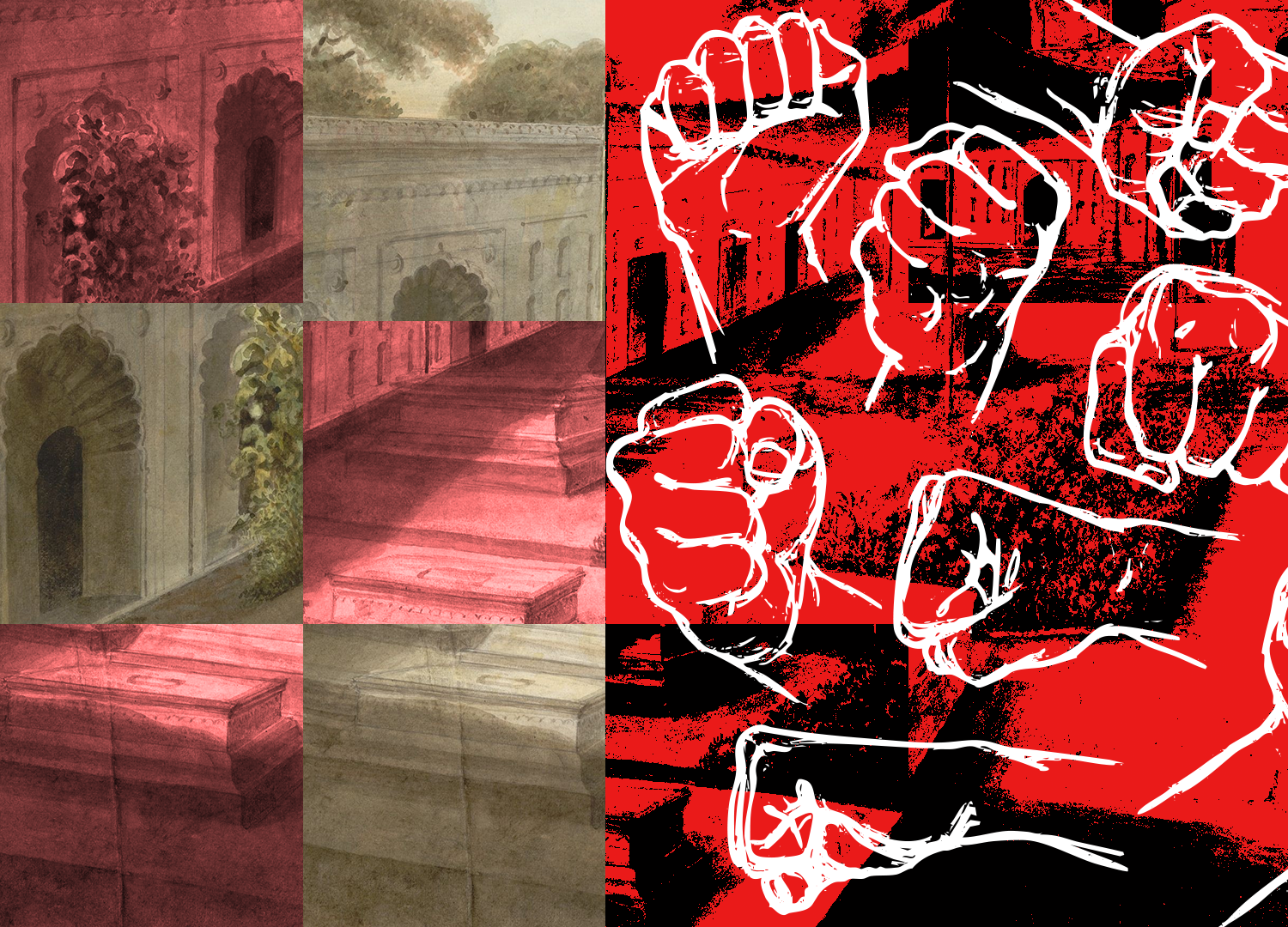

The spate of Islamist majoritarian vandalism is a signal from a political pressure group, and a symptom of the deeper issues plaguing Bangladesh’s politics.

A wave of vandalism in south-east Bangladesh, encompassing the University of Chittagong, Hathazari, and a Sufi shrine, came to the fore in national discourse, sharpening after the DUCSU election. A signifier of unrest and societal tension, it has broader implications born of longstanding underlying causes. As the Bangladeshi proverb observes: “Kings come and kings go, but it hardly makes a difference to anyone” (Raja jay raja ase, kar ki jay ase), highlighting the enduring resilience of society despite transient leadership changes.

Bangladesh, particularly the Chittagong region, possesses a rich Sufi heritage, with shrines and religious programmes, such as the observance of Eid-e-Milad-un-Nabi and various Sufi commemorations attracting large congregations. However, Hathazari Madrasa witnessed clashes between Sunni factions, resulting in extensive vandalism and injuries. The subsequent imposition of Section 144 by the Hathazari Upazila Nirbahi Officer (UNO) underscored the severity of these tensions. The broader implication is deeply concerning: religious clashes, whether ideologically or opportunistically motivated, can erupt at any moment, challenging social cohesion. The Quranic principle of honesty and integrity among fellow Muslims remains aspirational in practice, yet post-July, adherence to the religion’s code of ethics has diminished significantly. Individuals and groups presenting themselves as leaders and aspirants have failed to cultivate constructive political or social thought, illustrating the limitations of post-revolutionary hopes.

To contextualise these developments, from August 4th 2024 to mid-January 2025, over 40 shrines, Sufi burial sites, and dargahs experienced 44 documented attacks, involving vandalism, assault on devotees, robbery, and arson. A striking example is the attack on Nurul Haque’s (also known as Nural Pagla) Darbar Sharif in Rajbari’s Goalanda, which resulted in the death of 28-year-old Russel Molla. Such incidents signify a structural failure: police and administrative authorities have not adapted effectively since the July 2024 uprising. In the police ranks, notable gaps remain, with an absence of reforming the institution from the police state, pre-uprising days, resulting in a lack of direction regarding law enforcement, a glaring failure of the interim government. Absent too is accountability for crimes committed during the uprising period and prior to it, weakening the police force and rallying fundamentalist groups to operate without state oversight. Despite the end of a dictatorship, lawlessness persists in an environment where individuals feel emboldened to act. Immediate elections enabling administrative and bureaucratic reform are essential to restore order and public confidence. While right-wing political groups, including those who have close affiliations with the interim government, have been implicated in these attacks, the incidents reflect broader societal attitudes and normative behaviour patterns.

When religious extremists inflict injustice upon ordinary Muslims, they often act within perceived safe boundaries, disregarding social or moral responsibility by manufacturing pious, moral righteousness. Whether operating under authoritarian regimes or within democratic frameworks, such individuals exploit gaps in governance and societal vigilance. Consequently, ordinary Muslims, who engage sincerely in religious observances but do not subscribe to extremist ideologies or Islamist politics, frequently bear undue societal blame. Their commitment to personal faith becomes conflated with fundamentalist tendencies, rendering them vulnerable to social censure, state suspicion, and even broader misrepresentation in global narratives.

Addressing these challenges requires institutional intervention. The ministry of religion holds significant potential to curb extremism. By standardising this process and clarifying permissible and impermissible actions, the ministry could reduce doctrinal misinterpretation that fuels politicisation and radicalisation. Another crucial step is regulating who can deliver public sermons and monitoring their content, to prevent extremist narratives from proliferating among local communities. To achieve this, the ministry could adopt two systematic measures: establishing a fiqh justice board to standardise fatwas, and creating a board of wazins, to evaluate religious lecturers and instil intellectual rigour. Such institutional oversight would enhance inter-community trust, strengthen societal resilience against internal and external threats, and encourage self-regulation among Bangladeshi Muslims.

However, it would be difficult to achieve this in a non-partisan, depoliticised manner when the ministry is headed by an ideologue, as has been the case during the interim government’s tenure. It is probably why the inter-faith townhall meeting Muhammad Yunus hosted early in his tenure had the air of majoritarian Islamists – including individuals like Farhad Mazhar, who was featured prominently by Yunus’ team despite not representing any religion – lecturing to and imposing on everyone else. Worryingly, since then, the interim government has refused to meet the challenges of rising Islamism and the risks posed to religious minorities, including Muslim faiths. The patent falsehood relentlessly promulgated by Yunus, his press team and his advisers has been that these do not exist, and are only the product of disinformation from India.

Shifting focus from rigid doctrine towards equality and societal harmony remains critical, and necessitates an understanding and acceptance of local traditions and divergent interpretations of Islam. When upheld through conscious policy and ethical conduct, religious harmony can become a strong defence against radicalisation, fostering intellectualism, accountability and ethical expression in society. Furthermore, it forms the bedrock for the primacy of human rights and the state’s modernisation, without which citizens individually or collectively cannot survive, much less thrive.

The interim government has failed to establish effective administration in governance, law enforcement, and education. From this perspective, the revolutionary aspirations of July 2024 remain largely unfulfilled. Amid systemic failure, the dominant political thought and leadership practices remain stagnant. The vandalism at the University of Chittagong exemplifies this disconnect. The incident occurred under the cover of night, yet it went unaddressed until morning, when police treated it as a formal state issue. Questions persist. Why was there no immediate intervention by the police? Why did the proctorial authority fail to engage directly? Why was there a lack of words and action from the interim government and political parties? Students were left to confront the aftermath on their own, reflecting systemic neglect in times of crisis.

Public perception of governance and religious leadership has evolved over time. Prior to Sheikh Hasina’s tenure, criticisms of her administration’s treatment of religious leaders were common. Presently, however, the socio-political landscape and dynamics have shifted. During episodes of religious violence, ordinary Muslims often feel unsafe, reinforcing the belief that historical dictatorships and contemporary extremist groups differ little in their impact. This imposes a majoritarian religious duty – disguised as a moral duty – on every citizen, which they are to strictly adhere to in the name of social cohesion and political stability. For Islamist parties, this allows proselytisation of theocratic dogma, passed off as religious devotion. Incidents such as Hathazari, encouraged and carried out by those on the religious right who have been given a sizeable platform by the interim government disproportionate to their popularity or electoral significance, highlight the importance of societal awareness in preventing exploitation of public sentiments arising from a lack of knowledge.

Equally concerning is that some student leaders, who once spearheaded the July 2024 uprising, now exhibit tendencies reminiscent of authoritarianism. In this inversion lies a revealing insight: lacking idealistic leadership and ethical vision, Bangladesh’s political landscape prioritises power, wealth, and personal gain over genuine public service. Movements, while initially gaining momentum, falter when leadership is divorced from principled philosophy, moral grounding, and long-term strategic vision. Successes, when achieved without ethical or ideological foundations, remain transient. Without principled guidance, movements collapse, public trust erodes, and the aspirations of revolution remain unfulfilled. Thus, what emerges is a cautionary narrative: in the absence of visionary politics and ethical leadership, even the most promising social movements risk dissolution, leaving the populace adrift and governance ineffective. That these student leaders have married this with a turn to the religious right deepens the concern.

The recent wave of vandalism in Bangladesh is not merely a series of isolated incidents but reflects deeper structural, societal, and ideological failures. From systemic administrative inefficiency to unregulated religious authority, from unaccountable policing to the stagnation of public political thought, multiple factors converge to create fertile ground for unrest. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive strategies: institutional oversight of religious practice, transparent and accountable governance, moral and ethical education for emerging leaders, and societal engagement to cultivate constructive political ideology. Only through such multifaceted intervention can Bangladesh hope to reconcile its revolutionary aspirations with practical realities, ensuring both social harmony and enduring progress.

Mizan Rehman is a student at the University of Chittagong.