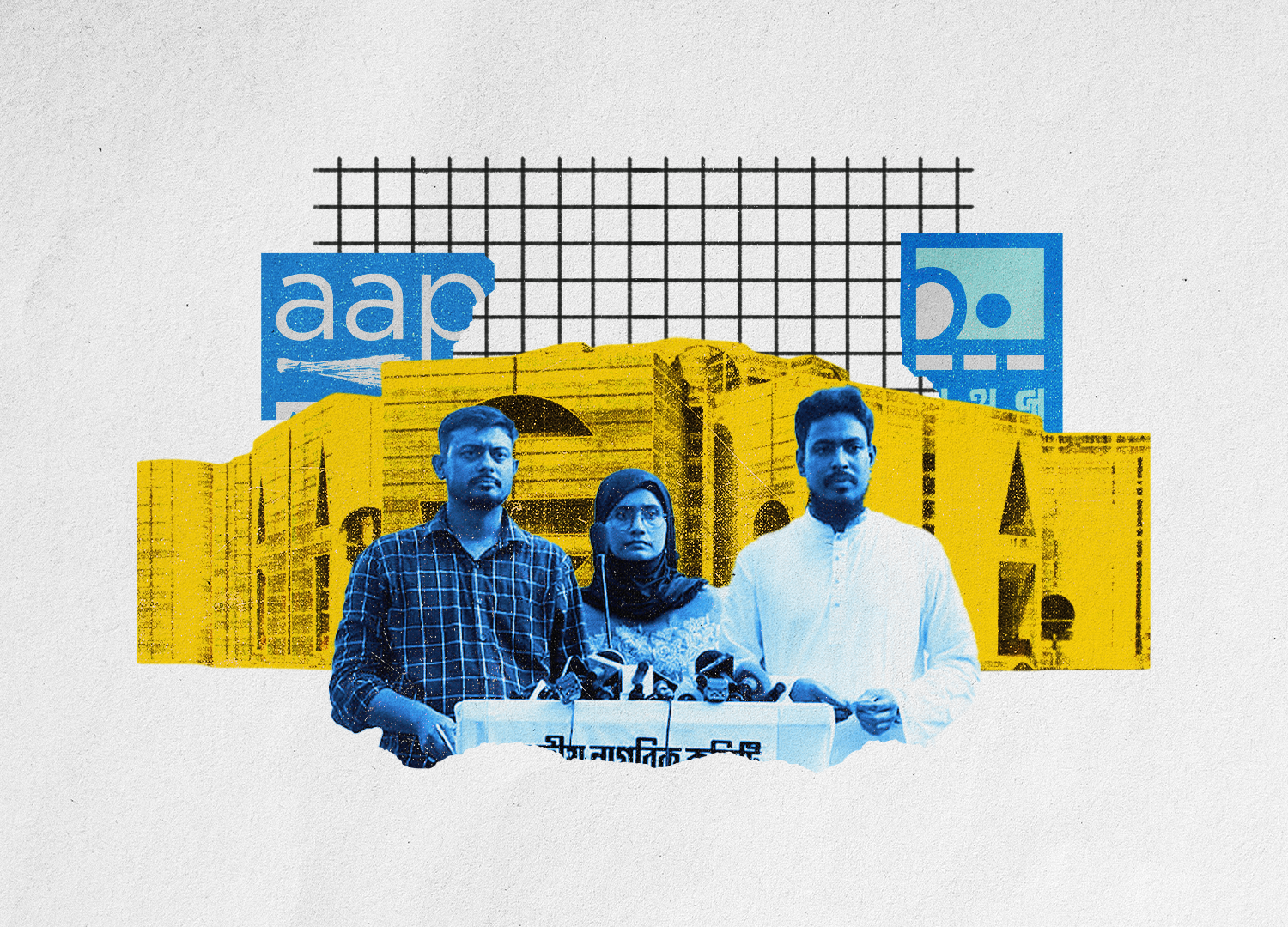

What does the new Zoomers Party stand for?

Will a students-led vehicle go far? Should it look to the subcontinent for clues?

A new party, once the great hope in steering the country away from the corrupt Big Two political parties, just had a cardiac arrest. It remains alive but is barely kicking. It provides salutary lessons for Zoomers (born between 1996 to 2011) about to embark on a political journey in the swamp of Bangladeshi electocracy.

I am referring to the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) in northern India. In 2012, an era of the Occupy movement and the Arab Spring, their urban middle classes were excited by the sudden entry of this new party on the subcontinent. Its leader, Arvind Kejriwal, had won a prestigious reward for his “Pariborton” (Change) movement against government corruption. Incidentally, Kejriwal’s journey began with resignation from his government job in 2006, the same year Muhammad Yunus won his Nobel Prize.

He had been part of the anti-corruption movement in 2011, led by Anna Hazare. “At the time…the comparison with Tahrir Square was freely and often made,” according to The Print newspaper. Hazare, the social activist, wanted to continue as a political movement. The ambitious Kejriwal wanted to plunge headlong into electoral politics and did so in November 2012. Kejriwal was seen as a new national leader for the first time from a non-BJP, non-Congress camp: prime ministerial material.

What was its ideology?

The party did not have a specific ideology at the outset. According to Kejriwal, “We are common men. If we find our solution in the Left, we are happy to borrow it from there. If we find our solution in the Right, we are happy to borrow from there.” The leader’s three pillars of core ideology were “staunch patriotism, staunch honesty and humanity”. That is not an ideology. It is merely a vacuous statement of values.

One might call it Centrist by default, given its equal-handed willingness to borrow from Right and Left. If there was any ideology it could be summed up as: zero tolerance of corruption. It gave no indication as to how it would eradicate malfeasance.

The AAP demanded a pushback against Ambani and Adani, but, crucially, without saying how. It has been described as the nearest India got to a colour revolution.

Despite local victories in Delhi and the state victory in Punjab, the AAP never became a nationwide force of note. A decade later, it has three out of 543 seats in Parliament. It has now lost Delhi.

Which way young Bangladesh?

The Jatiyo Nagorik Committee called in the cavalry. Farhad Mazhar spoke at a rally, pledging full support but seemed to wonder about its ideology and much postponed declaration. He suggested they firmly plant their flag on the terrain marked “people’s sovereignty”. That has deep, fundamental implications across the board but is it really likely to be taken up?

I came across an interesting schematic in social media. It discusses the political fault lines. Such as Shapla v. Shahbag contradictions. It mentions Farhad Mazhar as a standard-bearer of radical politics. It juxtaposes him with the conservative technocracy of Ahsan Mansur. While it is mentioned, economic development and how lives of the majority will be improved, will probably be low priority in a discourse top-heavy on narrow politics.

Even with a rare popular overthrow of the ancien regime, the students immediately handed over power to the Old Crowd. Old not in age but in thinking. Economic, financial and industrial development was handed over to technocrats. Even neoliberal economic think-tanks, and industrialists are up in arms about Central Bank Governor Mansur.

Zoomers have outsourced the economic levers of power to technocrats laden with their own ideology. It is not neutral, nor merely technical. While it is not Argentina’s chainsaw Millei, it is not state-led economic and industrial governance like Vietnam either. The political parties differ on culture, identity and versions of the “correct” history. There is very little difference in economics. This is not people’s sovereignty in action.

Sri Lanka just gave a thumbs-down to their own Big Two political parties, electing Anura Kumara Dissanayake on a platform pushing back against the IMF and the Western vulture funds. How radical it turns out to be in the medium-term is not clear. However, a small radical party (veteran of decades of turmoil) was able to stitch together a coalition, based less on culture and identity but on economic survival for the majority, reeling from harsh IMF austerity.

Sri Lanka is a couple of years ahead of Bangladesh in the political cycle. They overthrew Rajapaksa but then saw little or no change. Notice anything similar?

Returning to Delhi, The Print has this to say about AAP: “[T]he era of ideology-free politics is now almost over. For almost fifteen years, Kejriwal built a politics without any ideological pillar or foundation, and this was deliberate. His was an insurgent party that grew from street protest and urban middle class anger.”

Does the Jatiyo Nagorik Committee have an ideology?

Akhtar Hossain, member secretary of Jatiyo Nagorik, was interviewed on February 10th by The Daily Star. He said their new party would focus primarily on students (though he later mentioned they also wanted voters dissatisfied with “bipolar” politics). This led to a follow up question, asking if the government is struggling to connect with rural areas. His answer was illuminating: “[T]o truly connect with the people, the interim government must overcome barriers (bureaucratic constraints) and engage more effectively with the public”. No, nor me.

When asked what the core ideology and principles of the new party were, he responded: “Over 100,000 people have shared their opinions online. We’re now working on drafting the party’s constitution, declaration and agenda, while also consulting with experts and seasoned political observers.”

Deluged with opinions, one wonders if the leaders have their own filter, their own worldviews. It feels uncomfortably close to Kejriwal’s non-ideological, non-commital, so-called Centrist positioning. How many of the 100,000 respondents were rickshaw-pullers, construction workers, factory hands, farmers, workers abroad, nurses, transport workers and the rest? In other words, what is the class composition?

This has all the aroma of a new centre-right party. Centre ostensibly equals politically moderate. Maybe. Economically to the right, even if the students are not aware of it.

If morning shows the day, we are not likely to see the Anu Muhammad view of economic sovereignty being championed. Which is odd given months of widespread labour unrest, consumer anger, farmer distress and angst over lack of new jobs.

Recall, Kejriwal didn’t really want to do anything about Adani. It was just posturing, headline-seeking populism. But New Bangladesh surely should want to go to war with Adani over high energy prices and loss of sovereignty? That is the unfashionable politics of the National Committee to Protect Oil, Gas, and Mineral Resources, Power and Port. Phulbari, Rooppur, Rampal and more are not isolated battlegrounds.

We hear so much about the need for unity. Well, we already have it. For four out of five decades of the republic’s existence, there has been a bipartisan consensus on maintaining an unequal society: obscene wealth against invisible poverty, urban-centred in exchange for rural neglect, men over women. Has August 5th changed any of that reality?

The Road to 2030

One starts a political party after one has formulated an ideology and practised with a nationwide movement of activists, gaining local rapport and building coalitions.

Presumably, Plan A was precisely that within a four-year term. But, the moment they called in the technocrats, it was over. Perhaps Plan B is to give the BNP enough rope to hang themselves, figuratively speaking. I.e. the expected winners, the BNP, go on to mismanage the economy, as much as the current lot. Thus, leading to widespread dissatisfaction and anger, and then, who knows what. A second mass uprising? Or a 1/11 in reverse order?●

Farid Erkizia Bakht is a writer and analyst.