Why the BNP won — and what could yet undermine it

A patchwork of liberals, clerics and minorities formed an unlikely alliance that outmanoeuvred an organised Islamist push, but their support cannot be taken for granted.

A few months ago, it looked as if Jamaat-e-Islami had cracked the code.

It set out to build a grand front: Islamists of various stripes, July activists, even figures linked to the 1971 camp — all pulled together to ride a fresh wave of momentum.

But politics has a way of rewarding the less theatrical move. While Jamaat was busy stitching together an ambitious alliance, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) quietly gathered support from quarters many assumed were out of its reach. And that made all the difference.

The BNP’s coalition was not formally declared. It did not come with press conferences or grand announcements. It simply happened. Socially liberal voters, parts of the left, seculars, minority Hindu communities and even indigenous voters in the Chittagong Hill Tracts lined up behind a party they are not usually associated with. In the Hill Tracts, the BNP swept all three seats. For a party often portrayed as culturally conservative and majoritarian, that is no small shift.

Perception helped.

Jamaat was widely seen, fairly or not, as being close to the interim dispensation. When that government failed to protect the shrines of Sufi pirs and Sufi-aligned communities, the anger rebounded on Jamaat. In Sufi-heavy areas such as Sylhet and Chattogram, where it had hoped to make gains, its message simply did not land. In some places, its presence nearly disappeared.

Then there was the clerical question.

Figures linked to Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh openly opposed Jamaat. Its elderly chief, Muhibullah Babunagari, even declared that voting for Jamaat would be religiously impermissible. The tension is not new. Deobandi clerics have long been wary of the political Islam associated with Jamaat’s founder, Abul Ala Maududi. There are theological differences, but also something more practical: authority. Many Qawmi leaders feared that a stronger Jamaat would overshadow them.

Not all clerics felt the same, of course. Younger figures seem less averse to political engagement. There were moments of overlap between the two Islamist power blocks, particularly during the Shahbag period. They are also united by their hatred towards the Ahmadiyya community or even Sufi Muslims. Nonetheless, distrust lingered: a number of clerics, at times openly, leaned towards the BNP. Following the election, the Hefazat-e-Islam congratulated the candidates who won the BNP ticket.

For that, old relationships mattered too. The BNP’s longstanding ties with Bangladesh Jamiat Ulama-e-Islam — a party of Qawmi clerics that supported the 1971 liberation struggle — proved useful. Jamiat received generous seat-sharing, though it ultimately lost, often because of BNP rebels. Even so, the signal was clear: the BNP knows how to manage alliances, even imperfect ones.

Anticipating this Qawmi resistance, Jamaat had tried to widen its tent. It offered dozens of seats to Islami Andolon Bangladesh (IAB), led by a Qawmi-inspired pir family. That effort collapsed. Without IAB’s support and with Hefazat openly hostile, the grand Islamist front Jamaat had hoped for never quite materialised.

Some of its tactical moves fell flat. Recruiting Oli Ahmad, a decorated 1971 war veteran, was meant to blunt accusations about Jamaat’s past. His party was wiped out. The one bright spot was the National Citizen Party (NCP), born from students who participated in the uprising of August 2024, which picked up six seats and ran strongly elsewhere.

However, it would be foolish to dismiss Jamaat’s showing.

Its online campaign was sharp and disciplined. It framed the BNP as simply another incarnation of the Awami League, a party-in-waiting that needed checking before it consolidated power. That argument travelled well on social media. Roughly 70 seats and over 30% of the popular vote is no small feat for a party that had never obtained more than 15% of the electorate.

And nowhere did its digital energy matter more than in Dhaka.

The capital has long been tricky terrain for Jamaat. Yet this time it broke through. In Dhaka-17, Jamaat’s candidate — a relative unknown — ran Tarique Rahman surprisingly close in one of the country’s most affluent constituencies. In Mirpur, the party chief himself won by over 20,000 votes. At least six seats across the district went Jamaat’s way — a tremendous feat in a city that historically leans towards the likely winner. That said, serious BNP rebels in several seats chipped away at the party’s original vote bank, helping Jamaat’s advance.

But a new urban class is emerging: educated, mobile, impatient with what it sees as the transactional politics of both the BNP and the Awami League. It talks about integrity and self-respect. Jamaat has learned to speak that language.

First-time voters — those aged under 35 who missed the last credible election nearly two decades ago — made up more than 40% of the electorate. There was widespread speculation that, as seen in public university student union polls, this young, educated cohort would swing en masse towards Jamaat, driven in part by strong antagonism towards India. That does not appear to have materialised. Surveys suggested that younger voters still backed the BNP more than any other party.

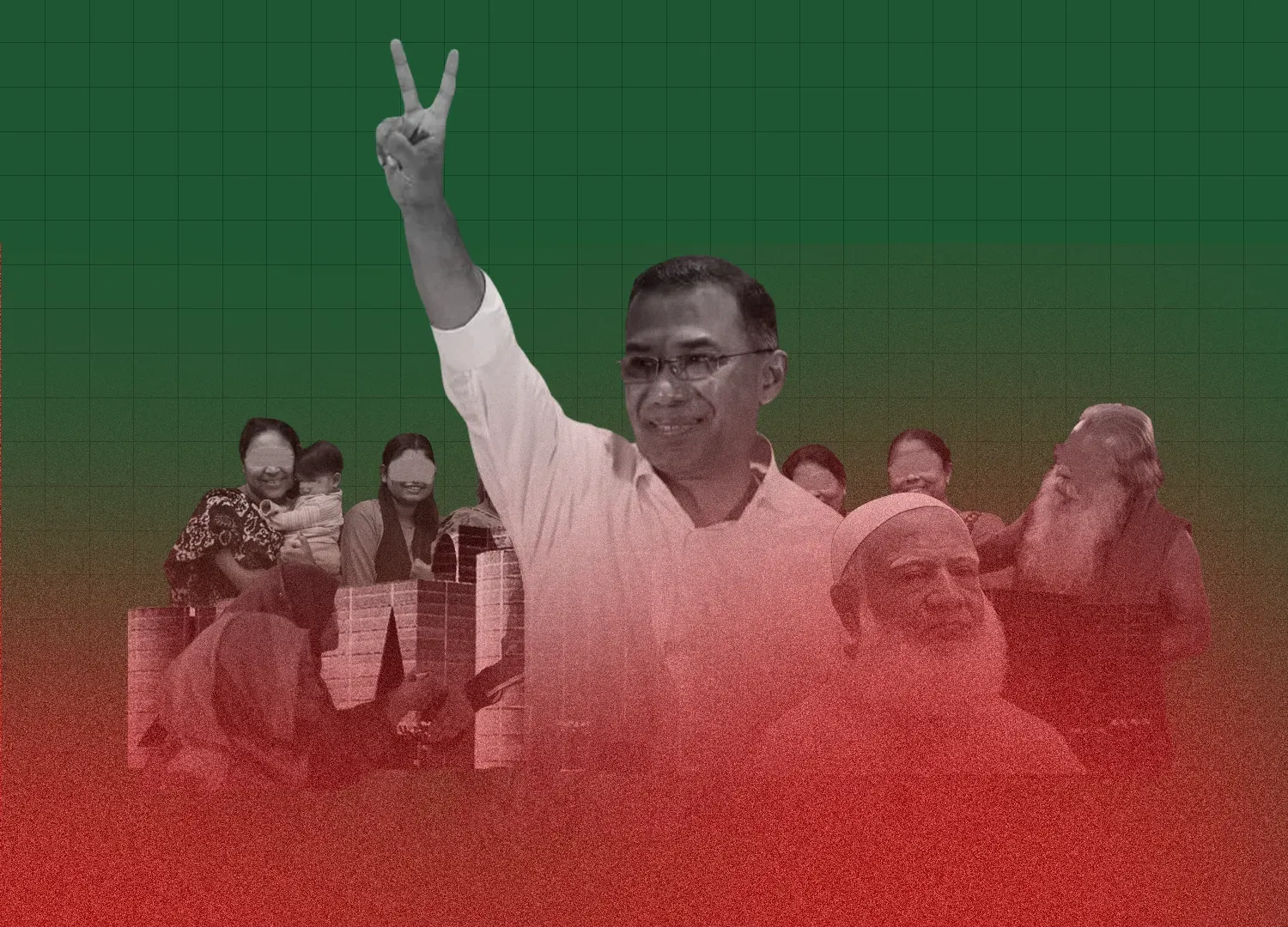

Young Jamaat-e-Islami supporters carry posters likening the party’s chief to lionised cinematic heroes, while a BNP rally draws a lower-income crowd. Photo: Jibon Ahmed/Netra News

There were other surprises. The assumption that women voters would automatically reject Jamaat because of its rhetoric, or its failure to nominate female candidates, did not quite hold. A Netra News analysis of more than 1,600 single-sex polling stations outside Dhaka found that, in the centres Jamaat carried, female-only stations outnumbered male-only ones. The BNP’s ratio skewed more male, at roughly 6:4. A new cohort of socially conservative women — often visibly religious — appears to be finding a sense of belonging and community in Jamaat’s message.

Regionally, some patterns were easier to read. Across Khulna and parts of Rajshahi, the Rapid Action Battalion moved against armed leftist groups during the 2001–06 period, effectively wiping them out. In Rangpur, the Jatiya Party began to wane after the death of Hussain Muhammad Ershad. In both regions, neither the BNP nor the Awami League had firm dominance. As local power structures weakened — whether through the collapse of leftist armed groups or the decline of the Jatiya Party — Jamaat gradually moved in to fill the space.

But Jamaat also nibbled at the BNP’s own base. The BNP is not built around tightly bound ideological cadres; it depends more on a broad supporter network. A slice of its traditional voters appears to have been drawn to Jamaat’s image of moral discipline. In Lakshmipur, for instance — long considered BNP territory — its candidates struggled to secure decisive margins against Jamaat challengers.

Even some Awami League supporters with a history of party activism seem to have lent Jamaat their vote. Their calculation was pragmatic: they feared a harsher crackdown under the BNP, whereas Jamaat struck a comparatively softer tone towards them. The wave of criminal cases — many widely viewed as fabricated — filed against tens of thousands of Awami League activists were largely initiated by local BNP activists, often as reprisals or, in some instances, as tools of extortion. Jamaat, by contrast, was far less associated with that campaign.

Women attend political rallies displaying Jamaat-e-Islami’s electoral symbol, the scales, alongside the BNP’s sheaf of paddy. Photo: Jibon Ahmed/Netra News

So why did the BNP still win?

Elections are not won on energy alone. They require machinery. The BNP has it. Jamaat, for all its organisational discipline, does not yet have the same nationwide depth across all 300 constituencies. The BNP’s candidates are veterans. They have fought and lost and fought again. In the middle of online noise predicting a Jamaat wave, they looked calm.

In the end, voters seemed to choose not ideological neatness, but plausibility. They may grumble about imperfections. What they want is a government that looks capable of running the place.

That is the prize the BNP has secured.

But it is also the risk. A coalition this broad is fragile. Liberals, clerics, minorities, rural networks, urban professionals — they do not all want the same things. If the BNP mistakes this moment for a blank cheque, it may discover that the quiet coalition which delivered victory can unravel just as quietly.

It is a pattern already seen. The interim government and the youth-led National Citizen Party first energised liberal supporters, only to lose them when they appeared to yield ground to more hardline factions.

The scale of the win is undeniable. The BNP secured more than a two-thirds majority in parliament, and its alliance won over 50% of the popular vote — a sizeable share by historical standards. Yet even that may not be enough to reshape the system entirely. If an upper house were created along the lines suggested in the referendum — allocated proportionally to popular vote share, rather than structured as the BNP had initially envisaged — its dominance there would be far less assured.

Jamaat has alleged irregularities in around 30 seats and called for recounts. That is a long way from the blanket rejection of results that losing parties in Bangladesh have often resorted to. Even if all 30 seats were overturned, the BNP’s overall victory would remain intact.

The fact that Jamaat has largely accepted the broader outcome suggests it may not behave like a conventional Bangladeshi opposition. It has pledged to remain active in parliament and announced plans to form a shadow cabinet — both unprecedented if carried through.

That leaves the BNP facing a different kind of challenge. The old playbook of handling the opposition through force or marginalisation may not work in the same way. And it would not take much for the public support it has just earned to begin to erode.●