Neighbour, not nemesis: Bangladesh in the Indian media mirror

To editors, journalists, producers, and opinion‑makers in India: check your facts. Don’t outsource your understanding of an entire nation to anonymous ‘sources’ and viral WhatsApp forwards. We are not asking for flattery. We are asking for accuracy.

Bangladesh did not fall off a cliff on August 5th 2024.

India’s TV studios just decided it had.

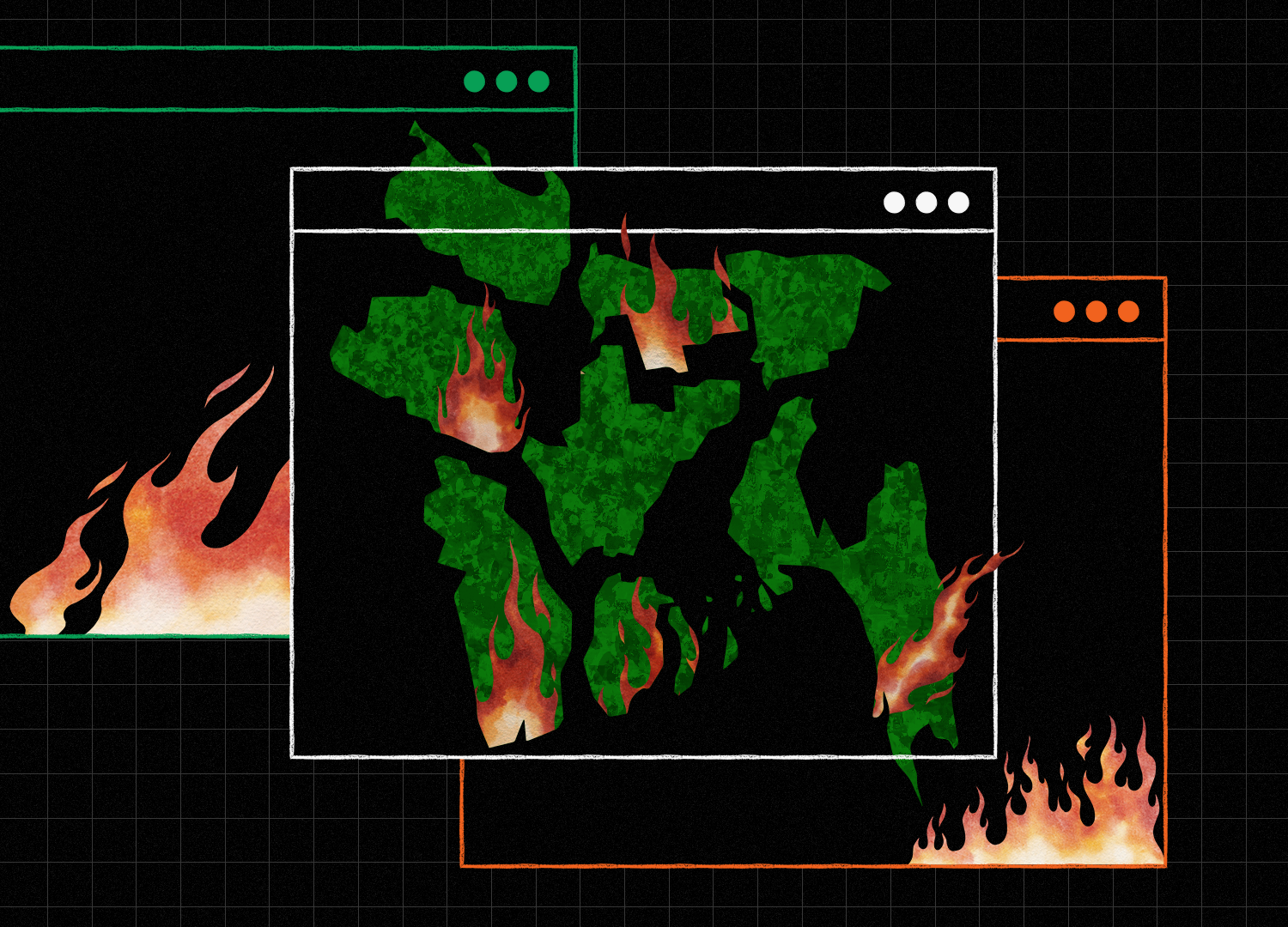

For over a decade, Bangladeshi realities were filtered through one convenient script in New Delhi: a ‘Golden Era’ anchored in one leader, one party, and one idea of ‘stability.’ When that script was torn up by students with backpacks and placards instead of guns and grenades, much of the Indian media did not adjust its lens; it simply changed its villain. Overnight, we went from a ‘trusted partner’ to a ‘hostile neighbour,’ from a ‘model of development’ to a ‘potential Pakistan,’ that is, Pathan’s next villain.

What follows is not just a critique of disinformation rather a plea for facts over fantasies, for nuance over noise, and for the modest recognition that 170 million people across a 4,000 km border are more than a supporting cast in someone else’s security drama.

For years, Indian commentary treated Bangladesh as an extension of its own comfort zone. Our stability was equated with one person’s grip on power, and our progress was measured by how reliably Dhaka echoed New Delhi’s talking points. When that edifice collapsed in August 2024, it was described not as a people’s liberation but as a ‘strategic earthquake,’ as if Bangladesh had committed an unforgivable breach of contract. Losing a guaranteed ally in Dhaka was cast as a gain for rival powers, and from that zero‑sum fear, paranoia flowed.

Within weeks, Bangladesh was no longer a neighbour in transition but a storyline in which every move had to be decoded as an anti‑India plot. If our students protested, it was ‘instability.’ If our courts acted, it was ‘elite revenge.’ If our army stayed in barracks, it was ‘proof’ that a coup was just around the corner. Reality became optional; geopolitics, compulsory.

Indian media did not simply ‘react’ to events rather it actively rewrote Bangladesh’s role in the neighbourhood, month after month, soon turning a flawed partner into a full‑blown problem.

August 2024

While the youth‑led uprising that toppled the Sheikh Hasina-led Awami League regime was globally recognised as a rare democratic jolt in the region, a plethora of Indian newsrooms treated the ‘Gen Z revolution’ like a suspicious software update — untested, dangerous, and likely installed by some foreign hacker. It was seen not just as a rebellion but a volatile one, easily hijacked by ‘foreign hands.’ We were no longer people; we became a risk factor.

September–October 2024

By early autumn, Dhaka was painted as a ship without a captain — “who really controls Bangladesh?” became a favourite debate topic. Our citizens were described, sometimes explicitly, as “ungrateful” for dismantling the so‑called Golden Era. The implication was clear: Bangladesh had traded established patronage for dangerous freedom, and India was the scorned benefactor.

November–December 2024

Then came the most toxic turn. It was the communal pivot.

Coverage began to lean heavily on stories of attacks on minorities — real and invented — ripped from political context and repackaged as proof that post‑uprising Bangladesh was turning into a Hindu‑hunting ground. Old videos from other countries, including India, were recycled as ‘temples burning in Bangladesh.’ One clip of an idol immersion in West Bengal did the rounds as ‘Muslims attacking a Hindu temple in Bangladesh.’ It would be comic if it were not designed to inflame millions of viewers.

The word ‘genocide’ crept into panel discussions. Bangladesh was now being marketed as a ‘Pakistan‑like’ cautionary tale: overthrow your strongman, and sectarian chaos will ensue. The secular student movement that lit the fuse of change was recast as the opening act for communal catastrophe.

January–June 2025

As diplomacy cooled, the coverage did not ask whether this ‘deep freeze’ served either people’s long‑term interests. It cheered it on.

Bangladesh was portrayed as a ‘hostile’ or ‘unreliable’ neighbour that needed to be ‘taught a lesson.’ Visa restrictions, especially for patients seeking medical treatment, were defended as tough but ‘necessary’ steps. Cultural exchanges quietly died too; our absence from events like the Kolkata Book Fair for the first time in decades was casually shrugged off as an obvious decision not to invite the unruly neighbour.

The underlying narrative was simple: Bangladesh understands only pressure. And if it insists on electing its own future, starve it of support until it learns to behave.

March–April 2025

When India Today ran the news of an imminent coup against Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus, complete with a supposedly conspiratorial army meeting, it was the perfect plot twist for a media arc building on “Bangladesh is ungovernable.” The small glitch was that the Bangladesh Army publicly called the story ‘false and fabricated,’ perhaps a polite way of saying “who writes your fiction?”

But retractions never travel as far as rumours. The damage was done. Bangladesh was cemented in the Indian imagination as a place perpetually on the brink, where the army lurks behind the curtain and any democratic arrangement is a fragile illusion. Add to that the fabricated open letter from Sheikh Hasina predicting doom, and you have a narrative cocktail: a weak interim regime, a looming coup, and a country unfit to manage its own affairs.

Mid–late 2025

By mid‑2025, Bangladesh had been assigned an even darker role.

We were cast as a potential hub for arms smuggling and extremism, stitched into a regional “terror arc” on the basis of anonymous sources and speculative graphics. Any independent foreign policy decision by Dhaka was interpreted as evidence of us becoming a “puppet” of rival intelligence services or great powers. Sovereignty, it seems, was reserved for bigger neighbours.

Culturally, the script shifted from shared roots to deliberate distance. Our absence from fairs, festivals, and collaborations was narrated as the natural price of our “anti‑India turn,” as though the deep ties of language, music, and history could be downgraded with a few panel discussions and a badly designed hashtag.

By late 2025, when Indian politicians spoke about border fencing, “illegal migration,” and eastern security threats, Bangladesh appeared less as a misunderstood neighbour and more as a convenient backdrop for tough‑on‑security posturing.

January–February 2026

As Bangladesh approaches its first post‑uprising election, many Indian media narratives portray Bangladesh as incapable of producing a democratic outcome that is both sovereign and ‘safe’ for India. The only acceptable result, it seems, is the return of a script our people have already rejected. Lest we forget, the start of the year also saw Bangladesh-India tensions impacting cricket, ultimately resulting in a T-20 World Cup kicking off in Sri Lanka and India without Bangladesh.

Meanwhile, stories are now emerging about a new generation of Bangladeshis sharply turning against India. Can anyone be surprised? Spend 18 months being told you live in a coup‑prone terror hub where your revolution is a mistake and your democracy is a risk, and you just might start to take it personally.

Independent fact‑checkers have catalogued well over a hundred pieces of outright false or grossly misleading content about Bangladesh in Indian media and India‑based social media over this period. Many came from long‑established outlets that once prided themselves on credibility. This exposed a pattern where sensationalism beats verification, and ‘Bangladesh in chaos’ pays better than ‘Bangladesh in transition.’

Some of India’s most recognisable logos dived in head first, armed with prime time graphics and a casual relationship with reality. For instance, when India Today breathlessly announced an ‘impending coup’ against Muhammad Yunus, you could almost hear the studio popcorn machine.

On the communal front, News24 and Zee News managed to turn a hotel fire into a Hindu temple attack in Bangladesh. It takes a special kind of talent to look at a burning commercial building and decide it is a shrine in another country — but ratings, like faith, can apparently move mountains. Fact‑checkers later confirmed the obvious. It was not a temple, not in Bangladesh, and not evidence of a “genocide,” unless you count the murder of context.

RT India joined the party by passing off a Kali idol immersion in West Bengal as an attack on a temple in Bangladesh. Somewhere between the ghat and the newsroom, geography was drowned. Bangladeshi fact-checkers traced the clip back to India, proving that in this new ‘information order,’ even the Hooghly can be rebranded as the Buriganga if the headline demands it.

Meanwhile, channels like Mirror Now were busy upgrading scattered incidents into a full‑blown apocalypse, with talk of ‘Hindus burnt alive’ and ‘mass killings’ that simply didn’t match verified numbers. Two confirmed deaths became the raw material for a rolling sermon on civilisational collapse. It was less journalism, more screenwriting.

Around them swirled the usual ecosystem of high‑decibel Hindi and Bangla channels — Republic TV/Republic Bangla, Zee 24 Ghanta, TV9, Aaj Tak, and friends — competing to see who could shout “Hindu genocide” and “Pakistan 2.0” the loudest every time “Bangladesh” appeared on the rundown. Nuance was treated like a hostile foreign agent; verification, like an optional add‑on.

This disinformation did not topple our interim government, but it chipped away at something far more fragile: trust. Trust between our citizens and their institutions. Trust that their prime time guests are not just playing to the gallery with our lives. Perhaps the most insidious thread in this tapestry is the sustained effort to delegitimise our interim leadership and, by extension, the idea that Bangladeshis can manage their own political transition.

Muhammad Yunus, the chief adviser, became a character in a rumour mill; supposedly gravely ill one week, alleged to have fled abroad the next, regularly depicted as out of his depth and out of control. The message was subtle but consistent: this government is flimsy, temporary, and eventually someone “serious” (read: in uniform) or someone “acceptable” (read: to New Delhi) will take over.

On the ground, media hostility has consequences.

When visas are suspended for patients needing Indian hospitals, it is not ‘geo-strategy,’ it is a woman in Khulna or Chittagong remortgaging her life because a door that had been open for 28 years suddenly slammed shut. When cultural exchanges evaporate, it is not ‘calibrated pressure’; it is two neighbours forgetting each other’s songs.

At the policy level, every minor friction over tariffs, river water, and ports is now framed in Indian debate as ‘weaponised interdependence,’ as though Bangladesh is a malevolent actor waiting to pounce. Any Indian policymaker who advocates dialogue risks being branded ‘soft on a hostile neighbour,’ while any Bangladeshi who asks for respect is caricatured as anti‑India. This is how a deep freeze becomes a self‑fulfilling prophecy.

Bangladesh wants, or rather has to have, a constructive relationship with India. We share rivers, history, borders, and blood. Geography is stubborn. What we are not willing to share is a future built on fiction. The era of a single point of contact, one leader, one party, one hotline, is over. We are building a more transparent, accountable, democratic Bangladesh, with many voices and centres of power. That may be messier than the old arrangement, but it is also more resilient.

To editors, journalists, producers, and opinion‑makers in India: check your facts. Don’t outsource your understanding of an entire nation to anonymous “sources” and viral WhatsApp forwards. We are not asking for flattery. We are asking for accuracy.

There is still time to write a better chapter. One in which Indian and Bangladeshi media disagree vigorously, criticise freely, and occasionally even mock each other’s blind spots, but do so on the basis of reality, not rehearsed hysteria. One in which our shared border is a place where ideas and opportunities cross more easily than fake news.

India has to realise that everything is not or does not have to be Bollywood. And if it is, then eagerly waiting for the next Pathan movie. I will not be surprised if the antagonist’s name is Yusuf.

Truth is not anti‑national. Nor is respecting your neighbour’s revolution. It is, in the long run, the only strategic asset that does not age badly.●

Apurba Jahangir was the deputy press secretary to the chief adviser Muhammad Yunus.