Bangladesh economy remains unstable with inappropriate policy settings

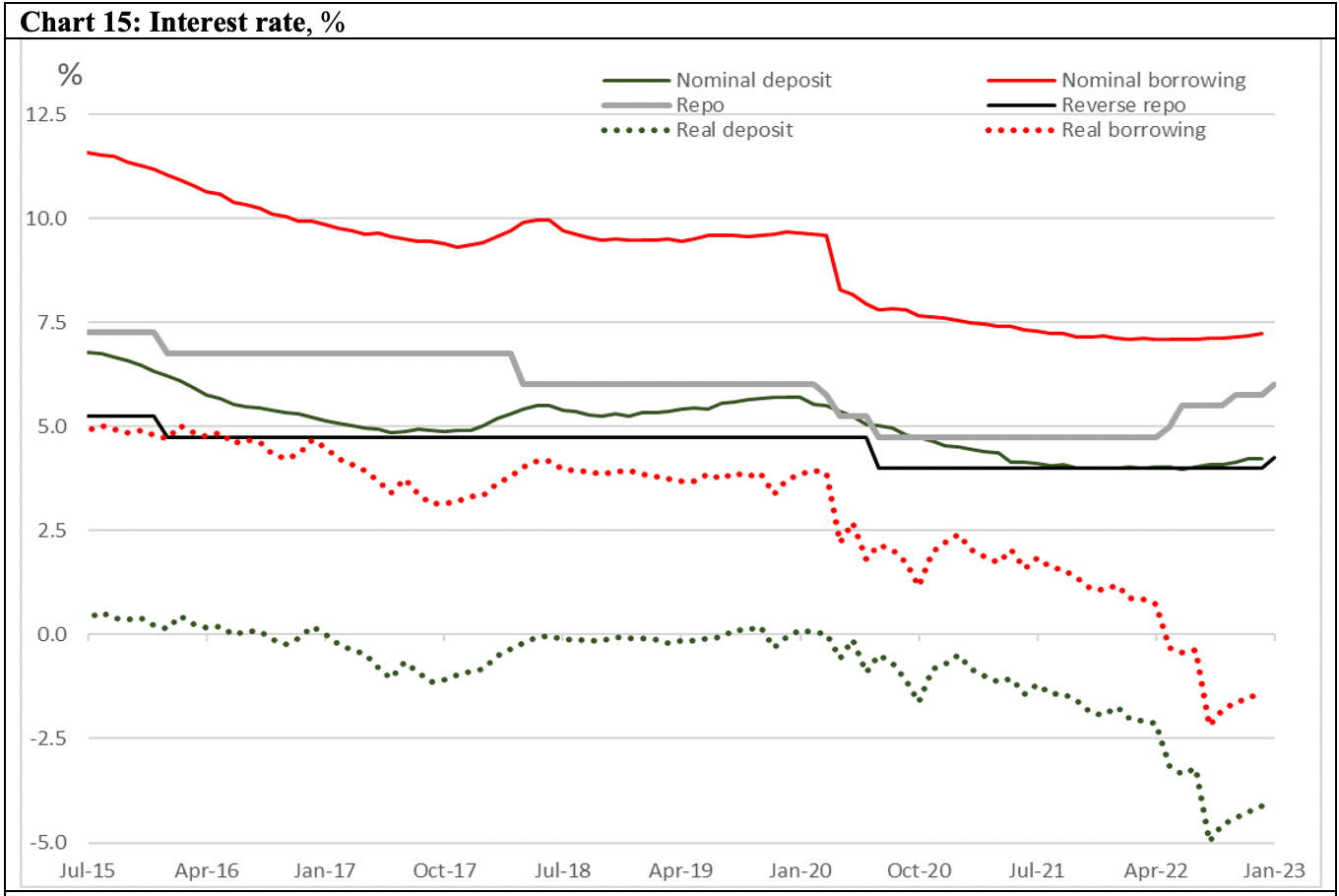

Tracking data shows that with interest rates remaining below the rate of inflation, private demand is fuelled, adding to inflation and increased imports.

This is the seventh edition of our set of 18 charts about the Bangladesh economy, with three months of further data. For more about the purpose and background of the charts and about the significance of each indicator, read the first article from March 2021 here.

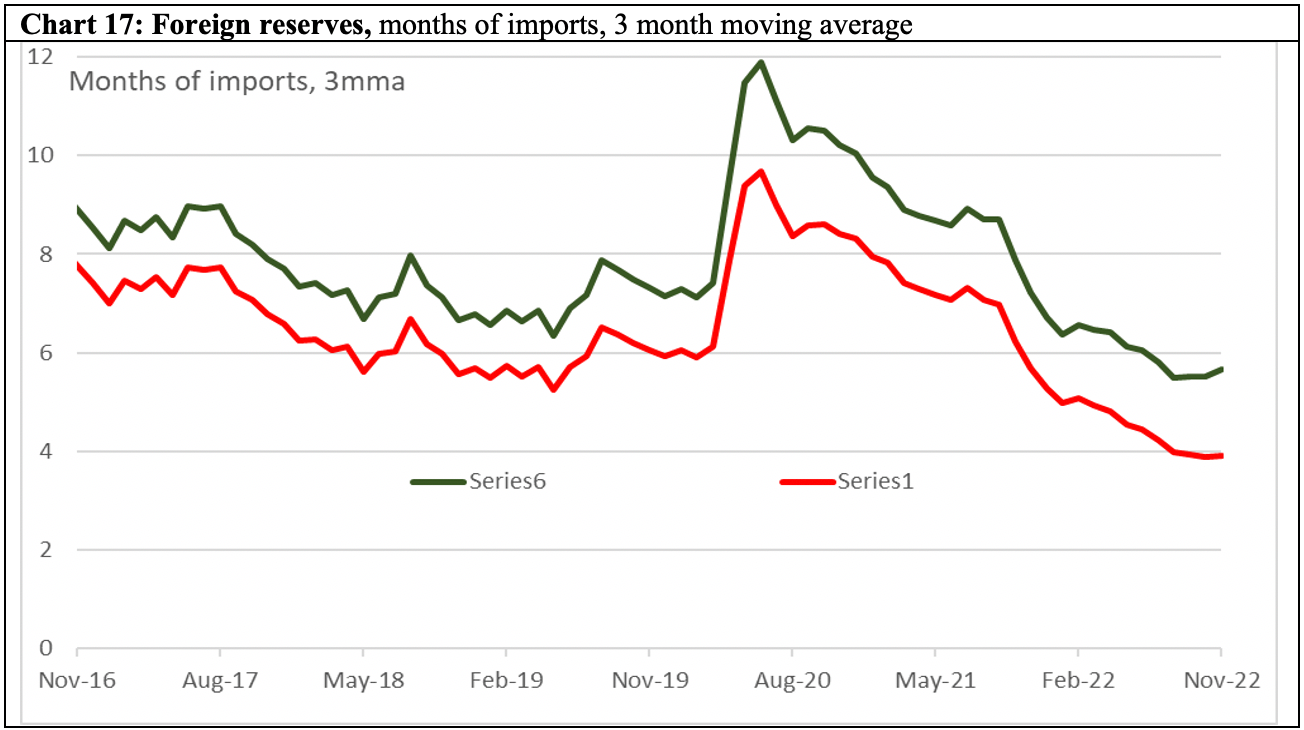

The last instalment in November 2022 showed that the economy was being buffeted by inflation and exchange rate uncertainty.The latest data shows that the policy settings are yet to adjust to the inflationary environment, and the macroeconomy remains dangerously unstable. With interest rates capped below the rate of inflation, the real cost of borrowing is negative. This is fuelling private demand and imports. In the meantime, remittances remain weak, reflecting expectations of further sliding of the exchange rate. Strong exports growth has helped stem the erosion of the Bangladesh Bank’s foreign reserves. However, with electricity shortages hitting productions, there are risks to exports performance. Fundamentally, the lack of transparency surrounding the exchange, interest rate, and fiscal policies is adding to the uncertainty.

It should be noted that the indicators only represent the urban, formal economy, and not the rural, agricultural, and the informal sectors. It’s hard to see the informal sector avoiding the inflationary environment prevailing in the formal economy. However, the lack of any explicit indicator of the agriculture sector presents an important caveat to the analysis presented. (In Bangladesh, financial years are from 1July to 31 June.)

Previous editions: March 2021; June 2021; September 2021; February 2022; August 2022; November 2022.

Overall Assessment

Buffeted by global inflationary shock, the economy remains unstable with inappropriate policy settings. Caps on interest rates remain below the rate of inflation, fuelling private demand, which is adding to inflation as well as raising imports. Meanwhile, uncertainties remain around the exchange rate, which is affecting remittance flows. Exports have remained strong, helping stem the erosion of the central bank’s foreign reserves. But problems in the electricity sector have started affecting industrial productions.

Chart 1: Electricity Generation

Prior to the pandemic, electricity generation was growing by 9-11% a year. After recovering from the pandemic in 2021, this series started slowing sharply into the summer of 2022. Growth in the series was less than 4% in the year to September 2022. The slowdown reflects the widespread loadshedding reported in the media in 2022.

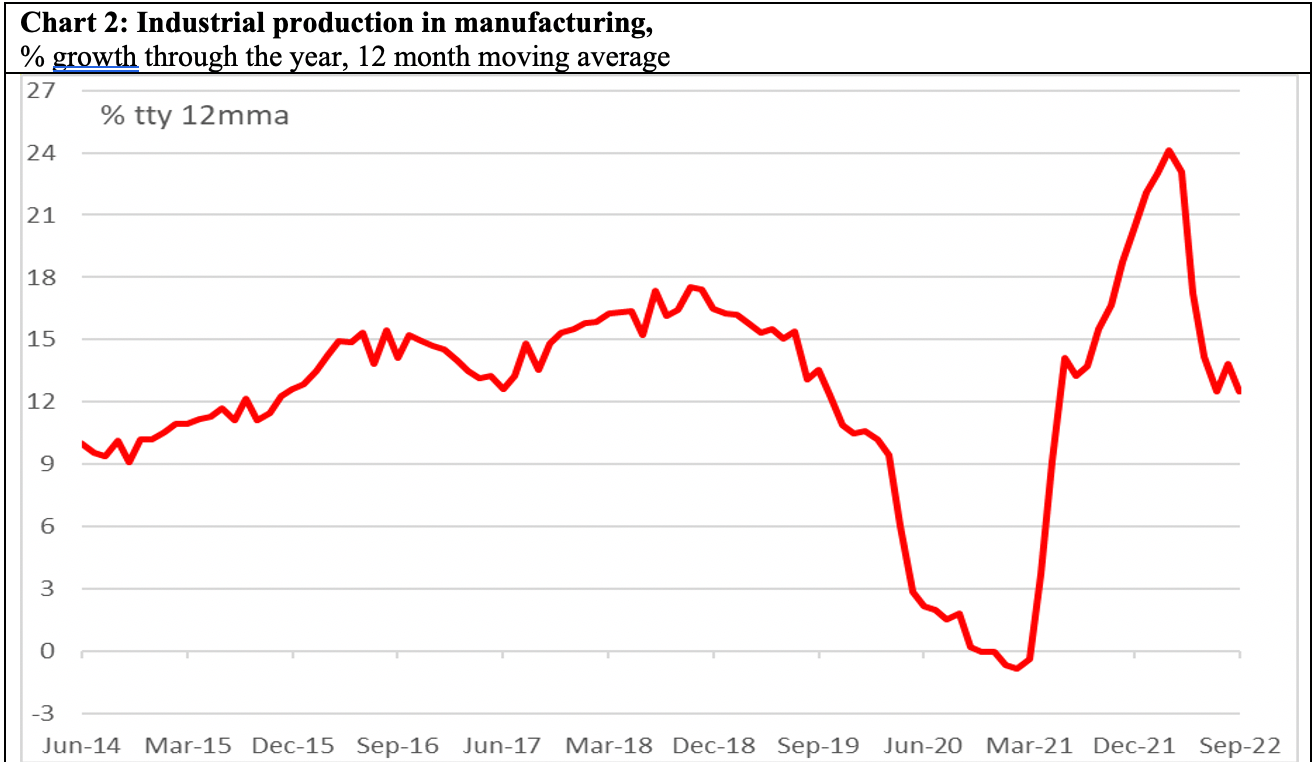

Chart 2: Industrial production

Prior to the pandemic, this series recorded yearly growth of 14-16%. Shaking off the pandemic induced stagnation, the series staged a rebound in the second half of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022. Since then, growth in the series has moderated to less than 13% in the year to September 2022. The slowdown in the series is consistent with the slowdown in the electricity generation as well as media reports of supply chain difficulties.

Chart 3: Exports

Exports also staged a strong post-pandemic recovery from mid-2021, which continued in 2022, with growth in the series of around 35% in the year to November 2022.

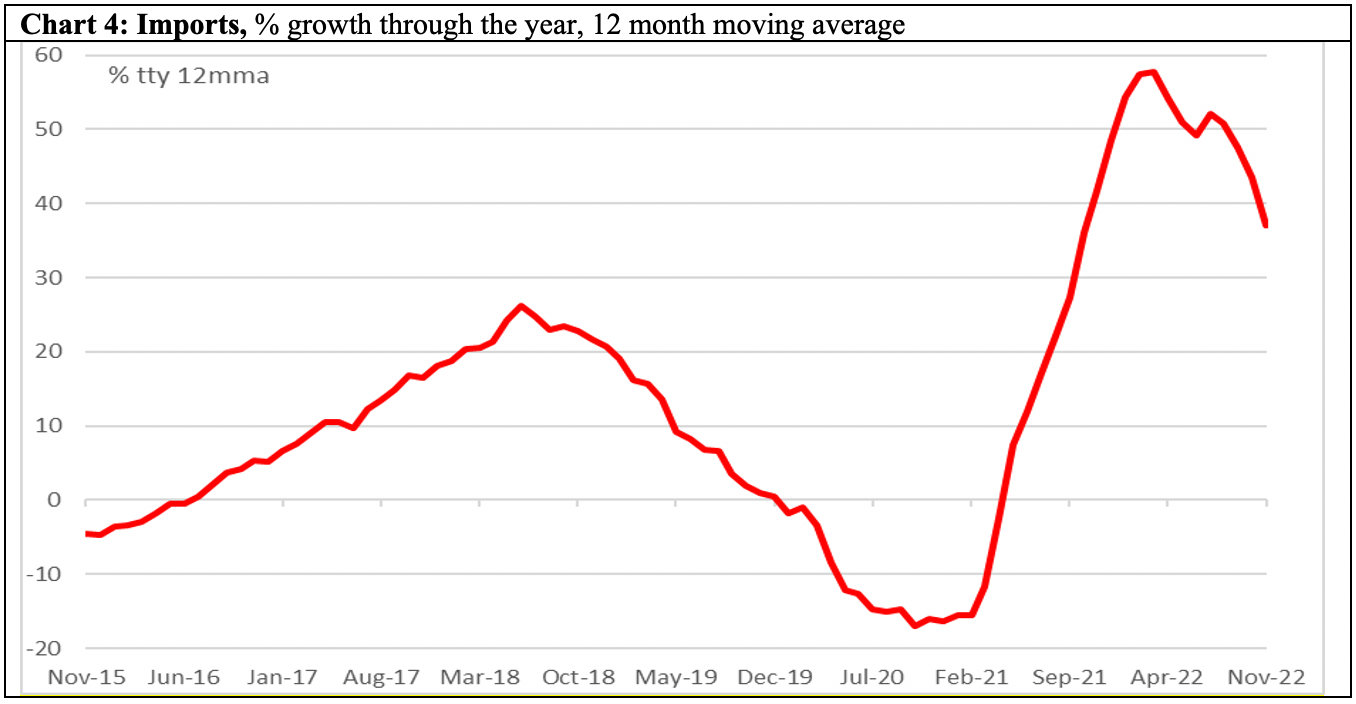

Chart 4: Imports

Imports also started recovering in mid-2021, consistent with signs of strength in other indicators. Imports growth surged further in the summer of 2022, partly reflecting high global energy and intermediate goods prices. Although moderating, imports were still growing by nearly 37% in the year to November 2022, significantly faster than the pre-pandemic period.

Chart 5: Credit to private sector

Growth in credit to private sector started slowing in 2018, well before the pandemic. The slowdown in the series bottomed out in mid-2021, and the series grew by nearly 14% in the year to December, similar to the 14-16% range witnessed in the mid 2010s. To the extent that the pick-up in this indicator reflects the negative real rate of borrowing (as the level of interest rates is lower than the rate of inflation, making borrowing very cheap - see Chart 15), this is a sign of economic imbalance and a harbinger of future instability.

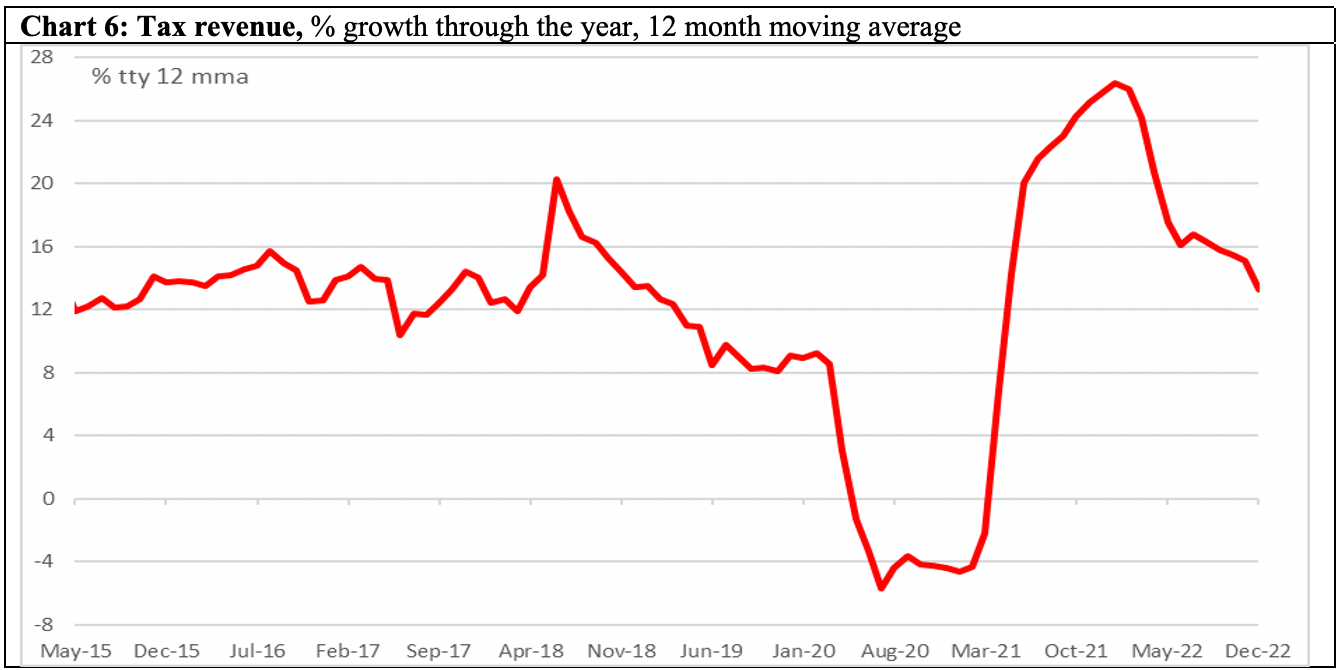

Chart 6: Tax revenue

Shaking off the pandemic slump, tax revenue grew strongly in 2021-22 financial year. While growth in the series has eased from the torrid pace of 2021, tax revenues were up 13% in the year to December 2022, compared with the 12-15% range witnessed in the mid 2010s.

Chart 7 and 8: Development and non-development expenditure

Both recovered in 2021-22, but the effects of austerity measures are visible in both series exhibiting declines in the first third of 2022-23 fiscal year.

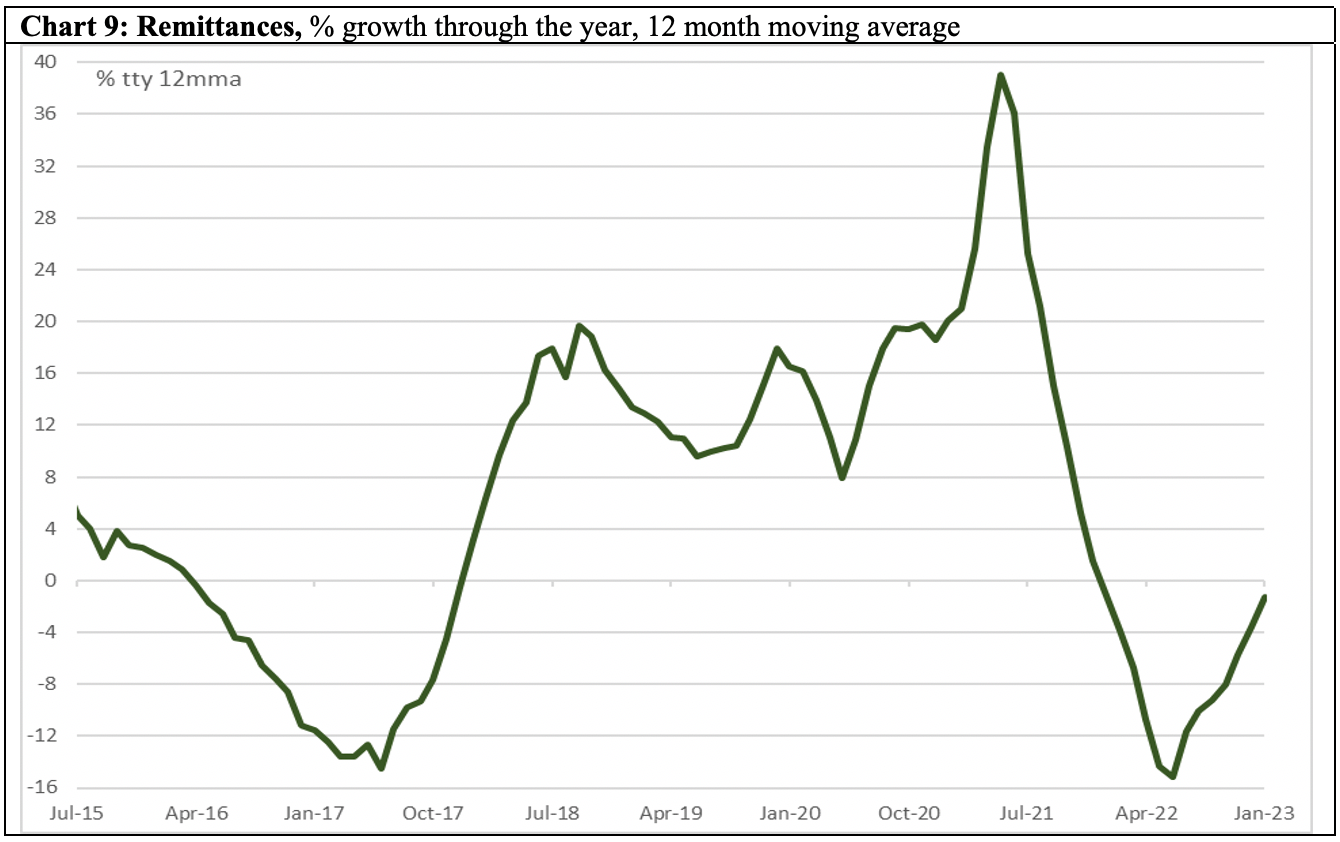

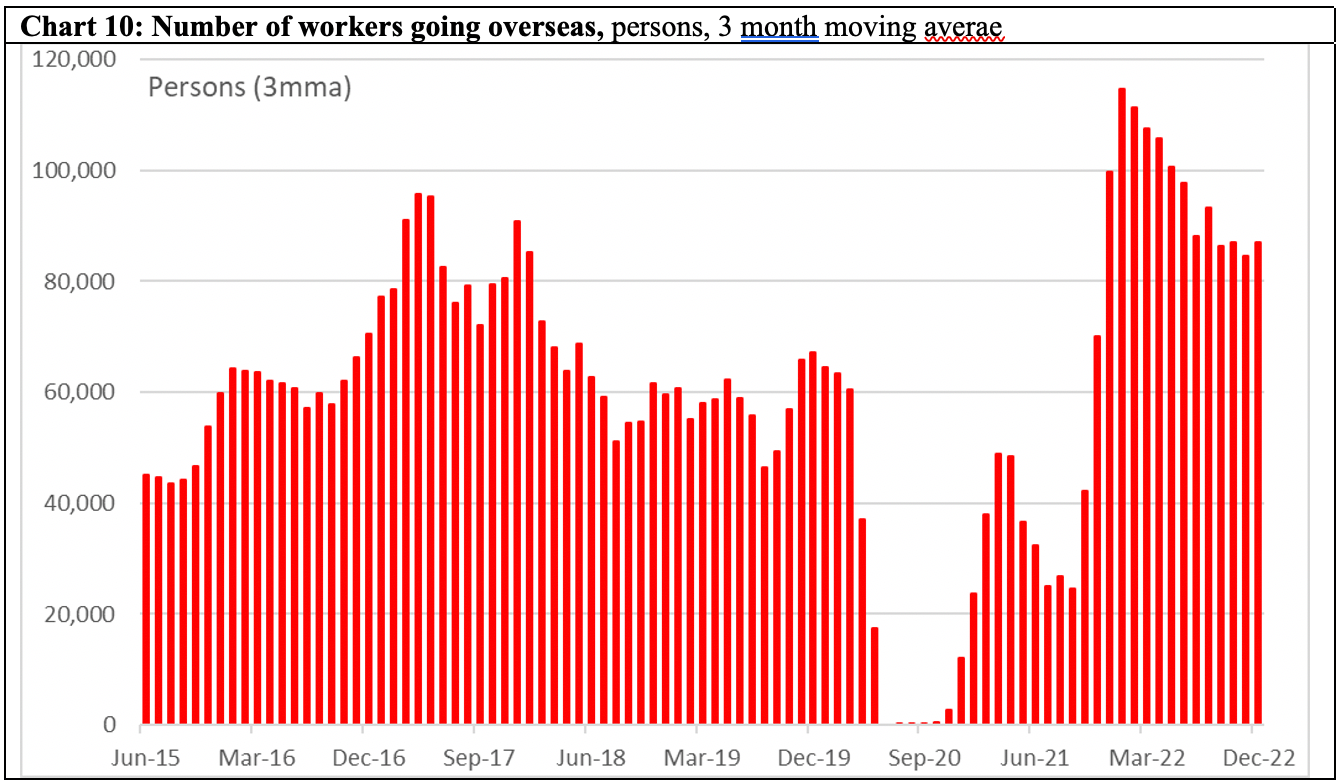

Charts 9 and 10: Remittances and Overseas Workers

The remittances have been exhibiting sharp volatility in recent years, likely reflecting the pandemic-induced disruptions in the informal hundi channel. Remittances slumped from record growth in mid-2021. In contrast, the number of workers going overseas staged a strong recovery, with record numbers leaving in the first half of 2022. Recent weakness in remittances despite the strength in the overseas workers series likely reflect the volatility in foreign exchange market, which discourages workers from using the formal channel to remit money. Specifically, given the concerns about foreign reserves, remitters may well be expecting further depreciation of taka in the coming months, and therefore holding off their current remittances through the formal channel.

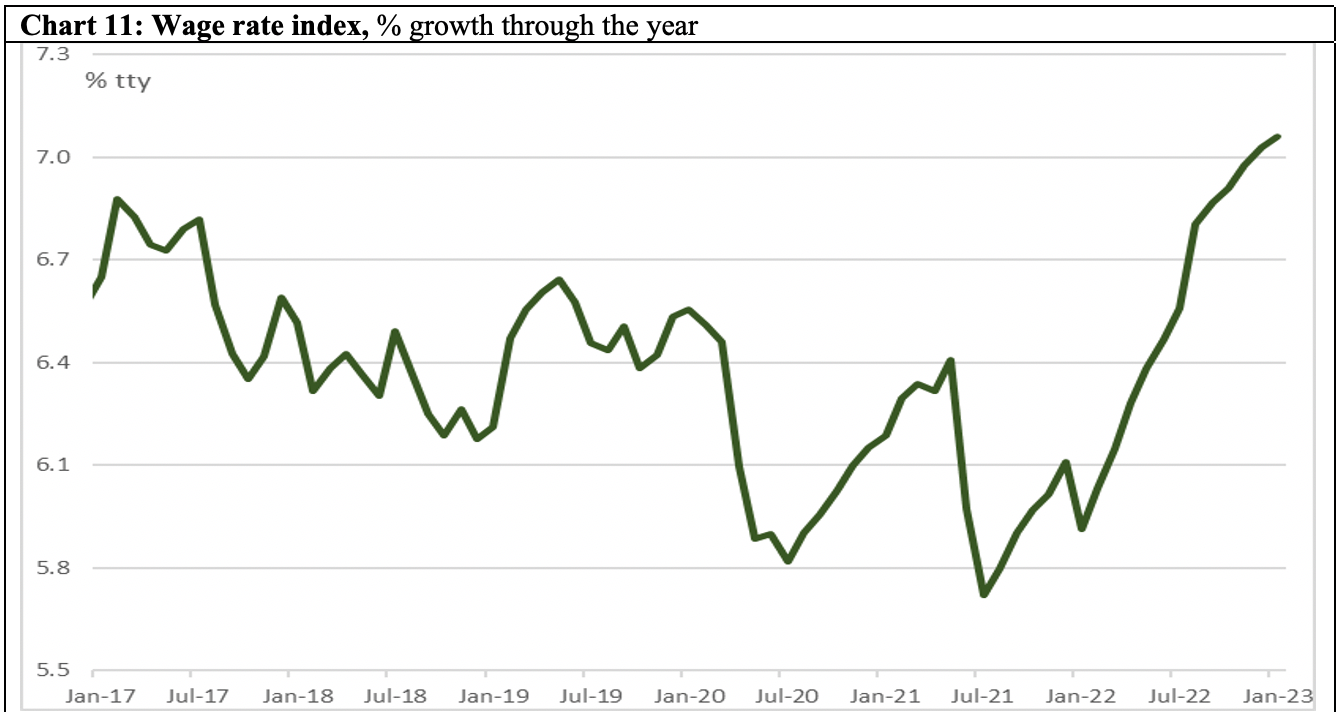

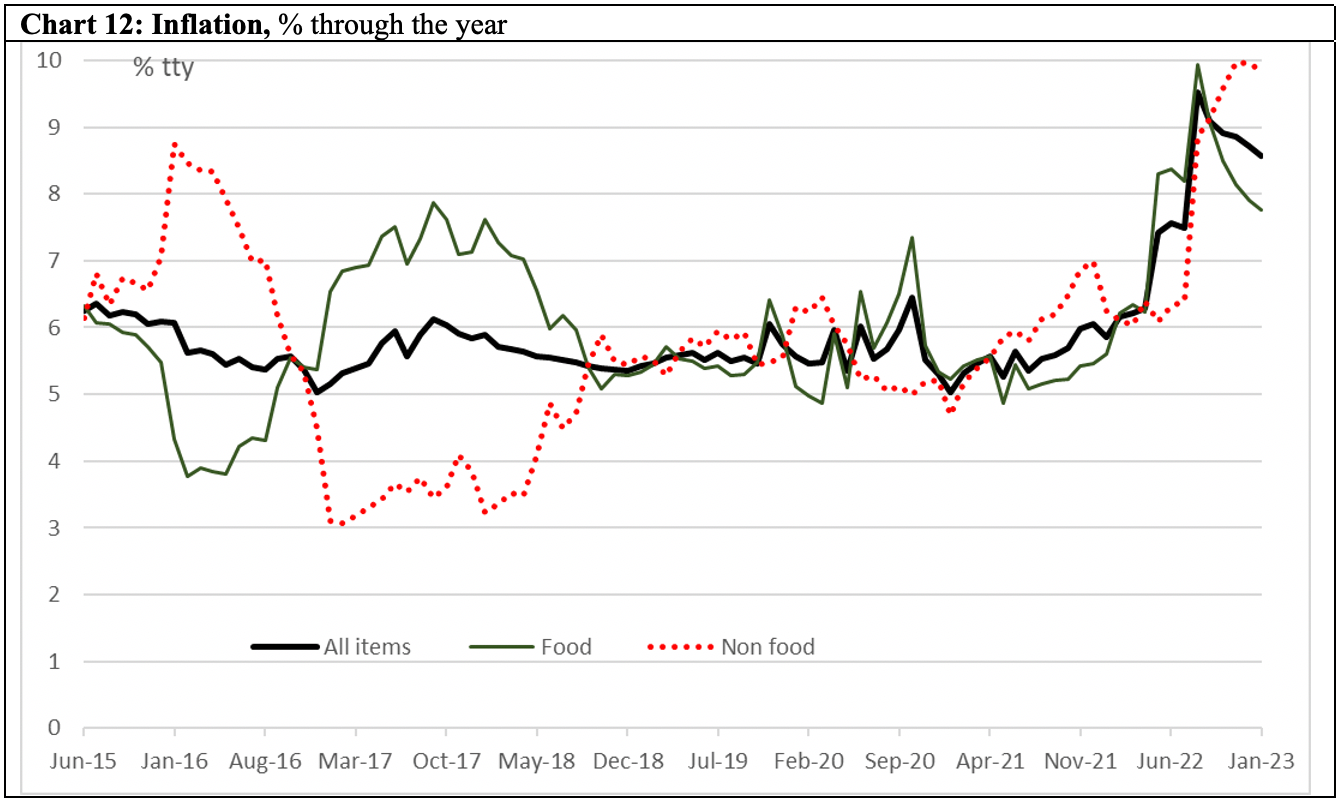

Charts 11 and 12: Wage rate index and inflation

Wage rates had grown by over 7% in the year to January 2023, consistent with the strength in various other indicators. However, inflation surged even faster, with consumer prices rising by nearly 9% in the year to January (non-food inflation was nearly 10%).

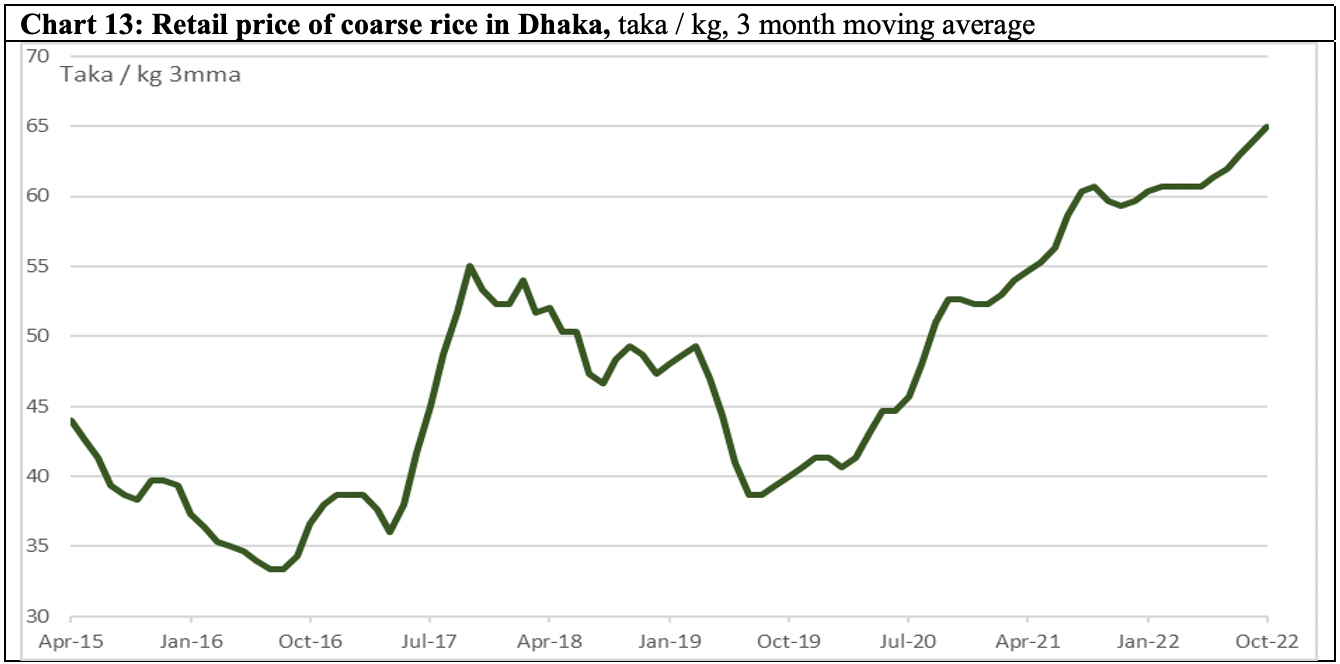

Charts 13 and 14: Price of rice and rental prices in Dhaka

The cost of living pressure was evident in the price of rice hitting a record 65 taka a kg in August 2022. Rental price index in Dhaka started recovering in late 2021.

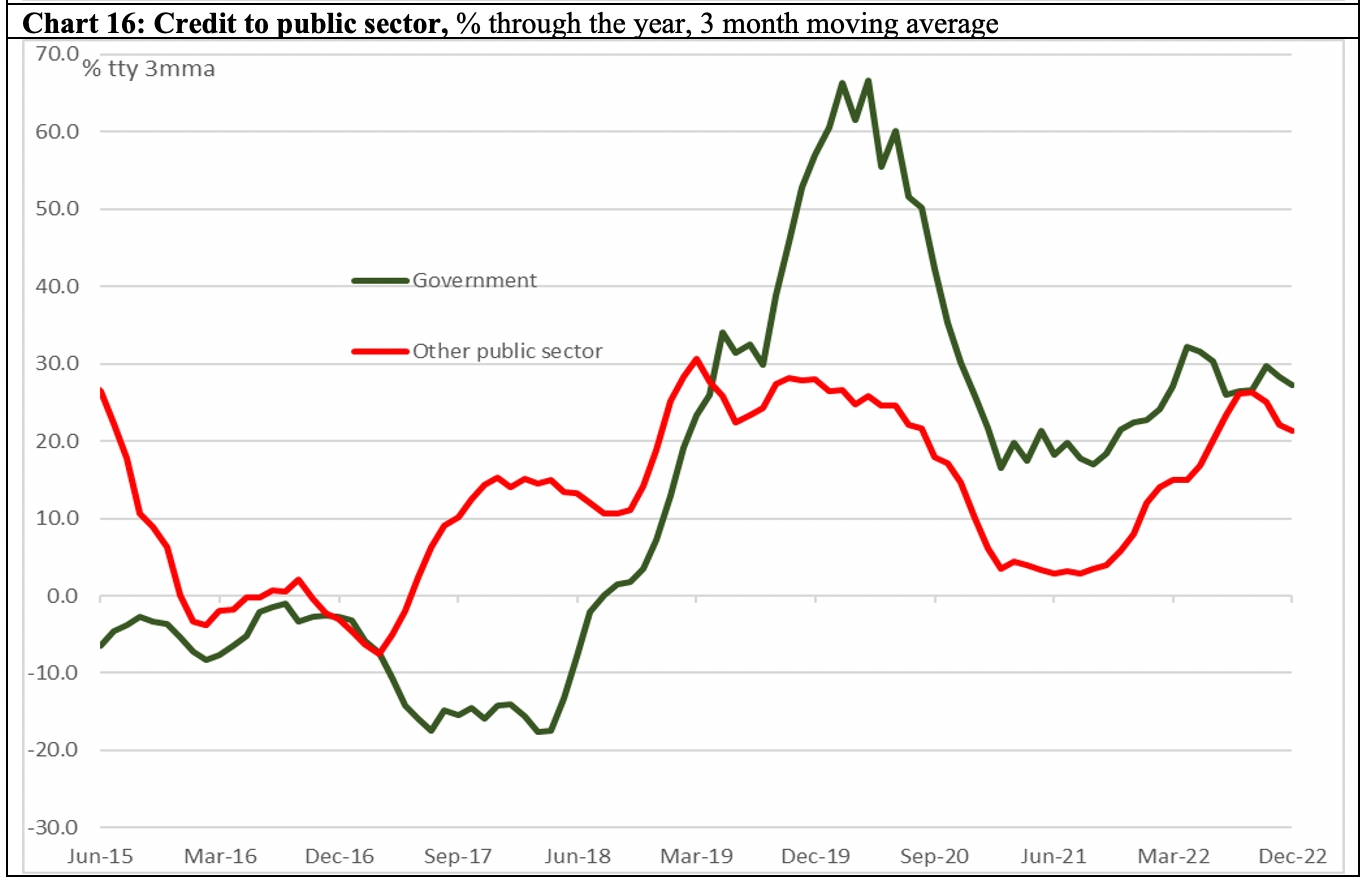

Chart 15, 16, 17: Interest rates, credit to public sector and foreign reserves

Bangladesh Bank cut official interest rates during the pandemic, and both deposit and borrowing rates tumbled. While the central bank has stated its commitment to stemming inflation, this is yet to be visible in the interest rates. In fact, with borrowing and lending rates capped, the real interest rate of borrowing is now negative. Public sector borrowing grew at a much faster pace in 2020-21 compared with the pre‑pandemic years, and is still growing at a brisk pace. That is, the macroeconomic policy setting is likely to be adding to inflation than curbing it. After declining steadily for months, Bangladesh Bank’s stock of reserves (measured in line with international standards) appear to have stabilised in recent months to cover four months of imports. While this is higher than three months that is usually considered adequate to support the exchange rate, given the recent strength of the US dollar in global markets, fast pace of imports growth, weak remittances, and high inflation environment, taka may well face further depreciation pressures.

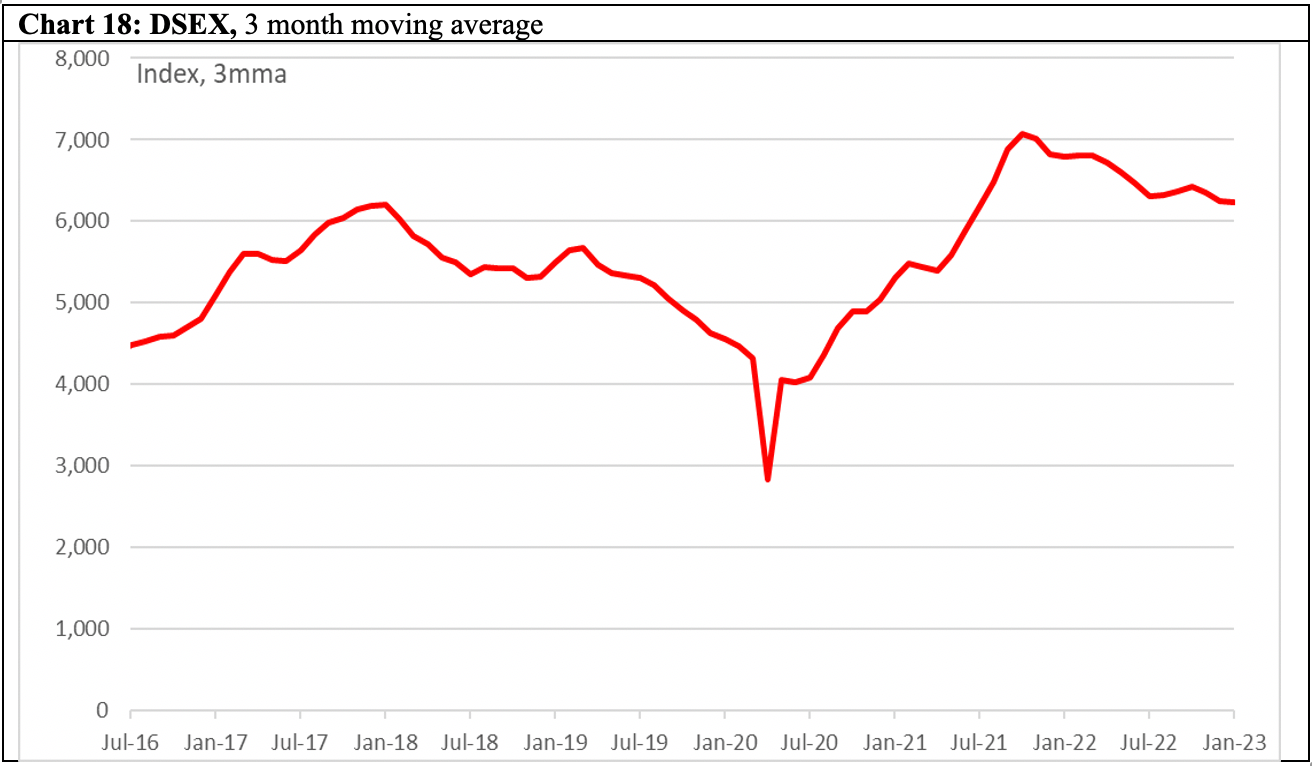

Chart 18: Stock Market

The Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSEX), remains stable.