Rogue reporter

At Associated Press’ Dhaka bureau, personal and political interests dilute journalism, as a reporter continually violates the news agency’s code of conduct.

After US Secretary of State Antony Blinken promised last year to impose visa restrictions against those manipulating the democratic process in Bangladesh and after the US State Department made good on the pledge a year later, the Associated Press has so far devoted only a single casual sentence to that tectonic shift in US-Bangladesh relations.

And in 2021, when the US government imposed unprecedented sanctions against Bangladesh’s security czars for gross human rights violations, it did not merit a standalone story by the iconic US news organisation, whose correspondent in Dhaka has not even mentioned such an exceptional censure in any of his numerous political reports.

Just like he has not ever brought up — with the exception of reports sharing the byline of another AP journalist — any reference to extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances, the most flagrant of the accusations labelled by prominent domestic and international human rights organisations against the government in Bangladesh.

In brazen public comments, the journalist has promoted hyper-partisan pro-government conspiracy theories against the Bangladeshi opposition and individuals critical of the government without citing any evidence, going as far as to accuse the US ambassador in Dhaka of “blackmailing” the Bangladesh government.

This extraordinary behaviour of the correspondent, Julhas Alam, matches a pattern of questionable conduct, an investigation by Netra News shows.

As a journalist for the respected newswire, Alam cultivated unusually close personal ties with key figures in the administration of the Bangladeshi prime minister and her ruling party — ties so intimate that they extended to at least one known instance of carrying out de facto public relations work for the government. When his wife, a ruling party politician, ran for office on the party’s ticket, Alam hopped in to campaign for her, appearing as an official polling agent. Even worse, he got involved with a private public relations firm and then quoted its major politician client in news stories. And, as per AP’s own statement to Netra News, he has even been inflating his own ties with the news organisation.

On its own, each count of these conducts constitutes a breach of the AP’s policies of impartiality, conflict of interests, and integrity. Taken together, they paint a picture of a journalist woefully inadequate to serve as a reporter, let alone for a news organisation on which countless newsrooms around the world professionally rely for best media practices.

“The Associated Press stands by its robust, fair and unbiased coverage of Bangladesh and remains committed to reporting on developments in the country and across Asia,” Lauren Easton, vice president for corporate communications at AP, wrote in an emailed statement to Netra News.

“As a nonpartisan global news organization, it is essential that AP report the facts, which includes covering all sides of a story.

“That said, we take any violation of AP standards seriously, and if any have occurred here, they will be handled internally.”

For the AP, which boasts a daily reach of whooping 4 billion people worldwide, Alam’s tainted coverage has left its audience interested in Bangladesh misinformed, an expert told Netra News, especially at a time of growing concern in liberal democracies about the rise of authoritarianism around the world.

“It is unfortunate to witness a reputable international news agency compromising balanced reporting and shaping news based on a journalist’s political inclinations,” said Fahmidul Haq, a visiting professor at Bard College in New York, adding that the AP should not tolerate a journalist who operates with “hidden objectives.”

Alam did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Ties that cross the line

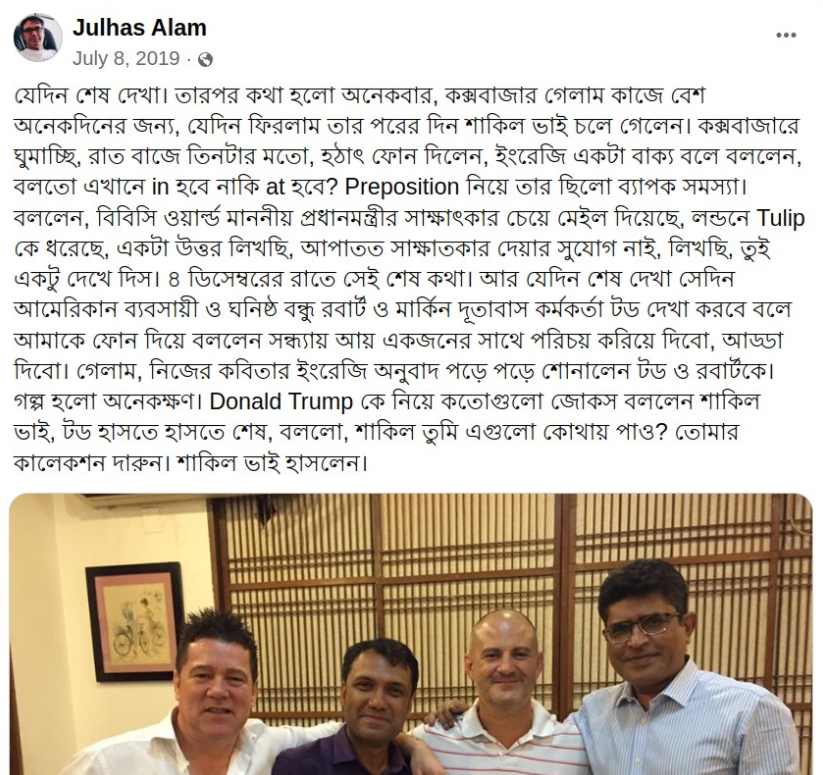

Alam maintained a close personal friendship with Mahbubul Hoque Shakil, who was special assistant to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina until he died in 2016. Both men partied together frequently, their social media accounts show, and Alam often delivered eulogies about Shakil, both when he was alive and after his death.

That intimate relationship appeared to affect Alam’s journalism.

As Alam recalled in a Facebook post, Shakil had once asked him to review a draft statement prepared by the prime minister’s office (PMO) in response to BBC World’s press queries.

He acknowledged, as if to reaffirm the closeness of his ties with Shakil, that he complied with the request, effectively handling the government’s press relations tasks while working as a journalist.

Shakil was also quoted in his news stories at least once every year from 2012 to 2015.

“It’s worth noting that journalists operating in difficult and politically fractious environments must develop sources on every side of an issue in order to report the facts fairly and without bias. This is part of the reporting process,” said Easton, the AP spokesperson, without referring to any specific instance.

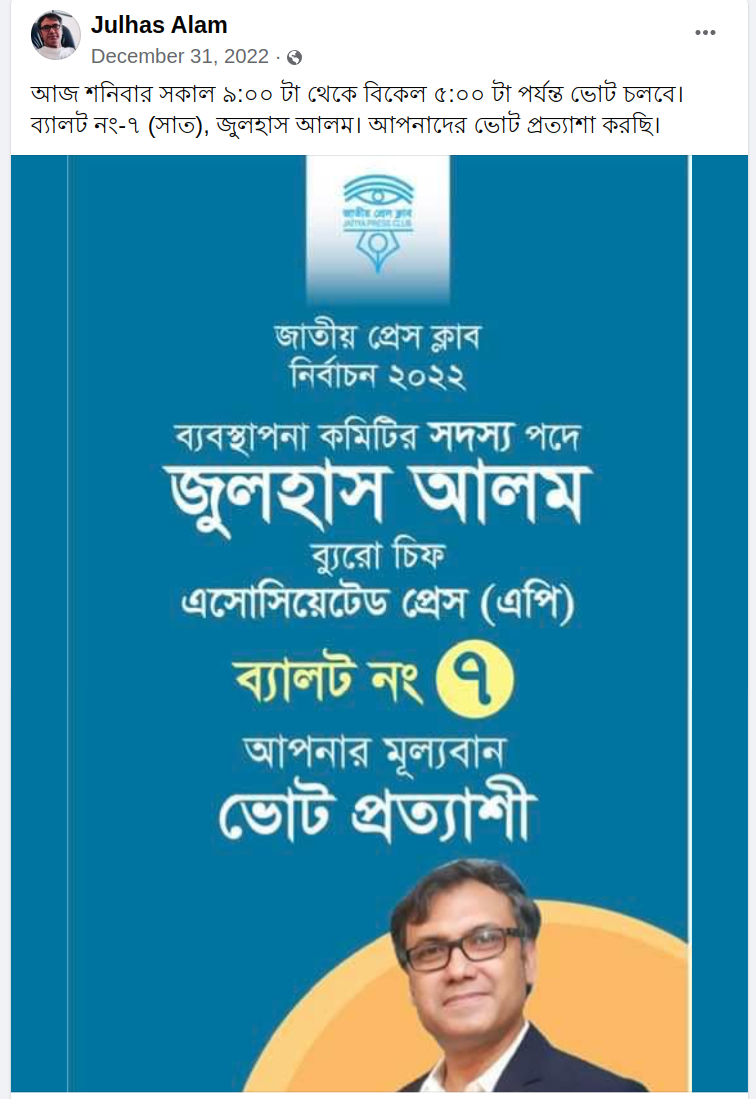

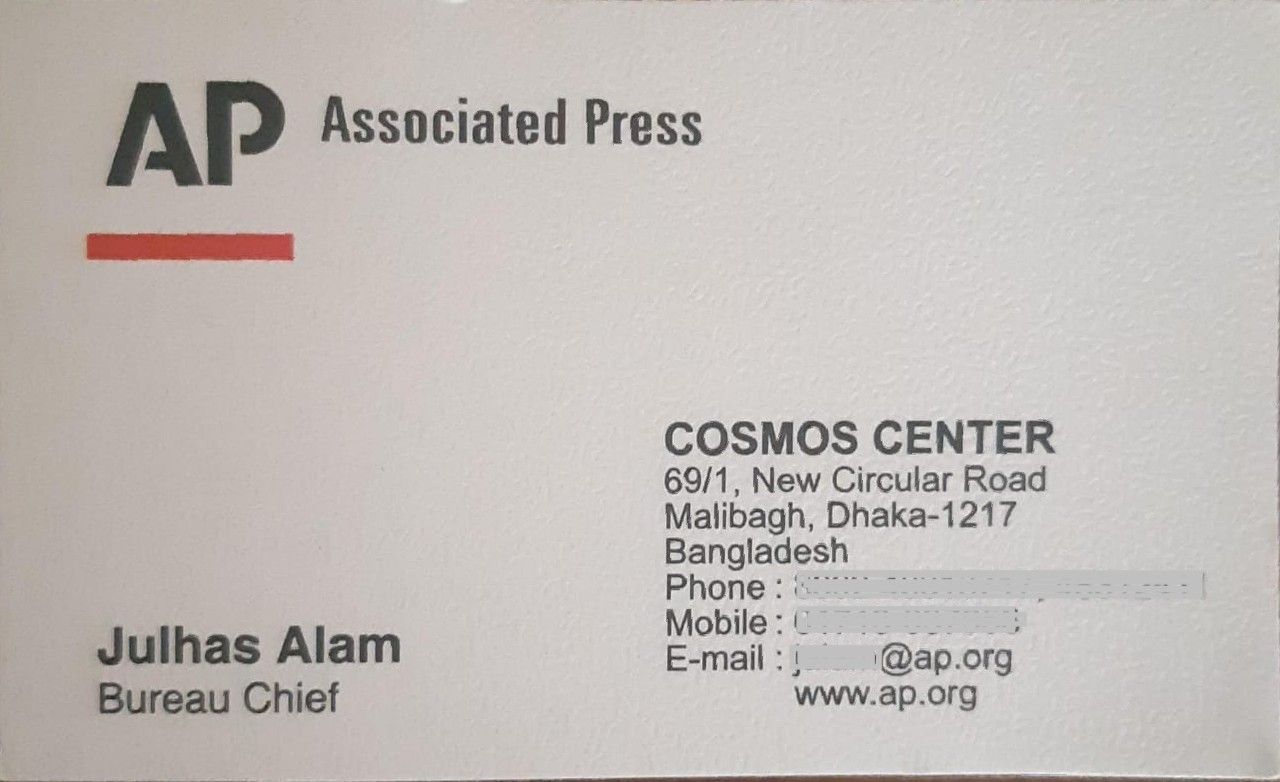

She, however, pointed out that Alam was working for the news organisation as a correspondent as opposed to its bureau chief in Dhaka.

That statement directly contradicts Alam’s claim of being the AP’s Dhaka bureau chief, including on his campaign posters for a position at Dhaka Press Club, which still lists him as the AP’s “Bureau Chief,” so does his official business card.

The AP did not comment on whether Alam was misrepresenting his press credentials.

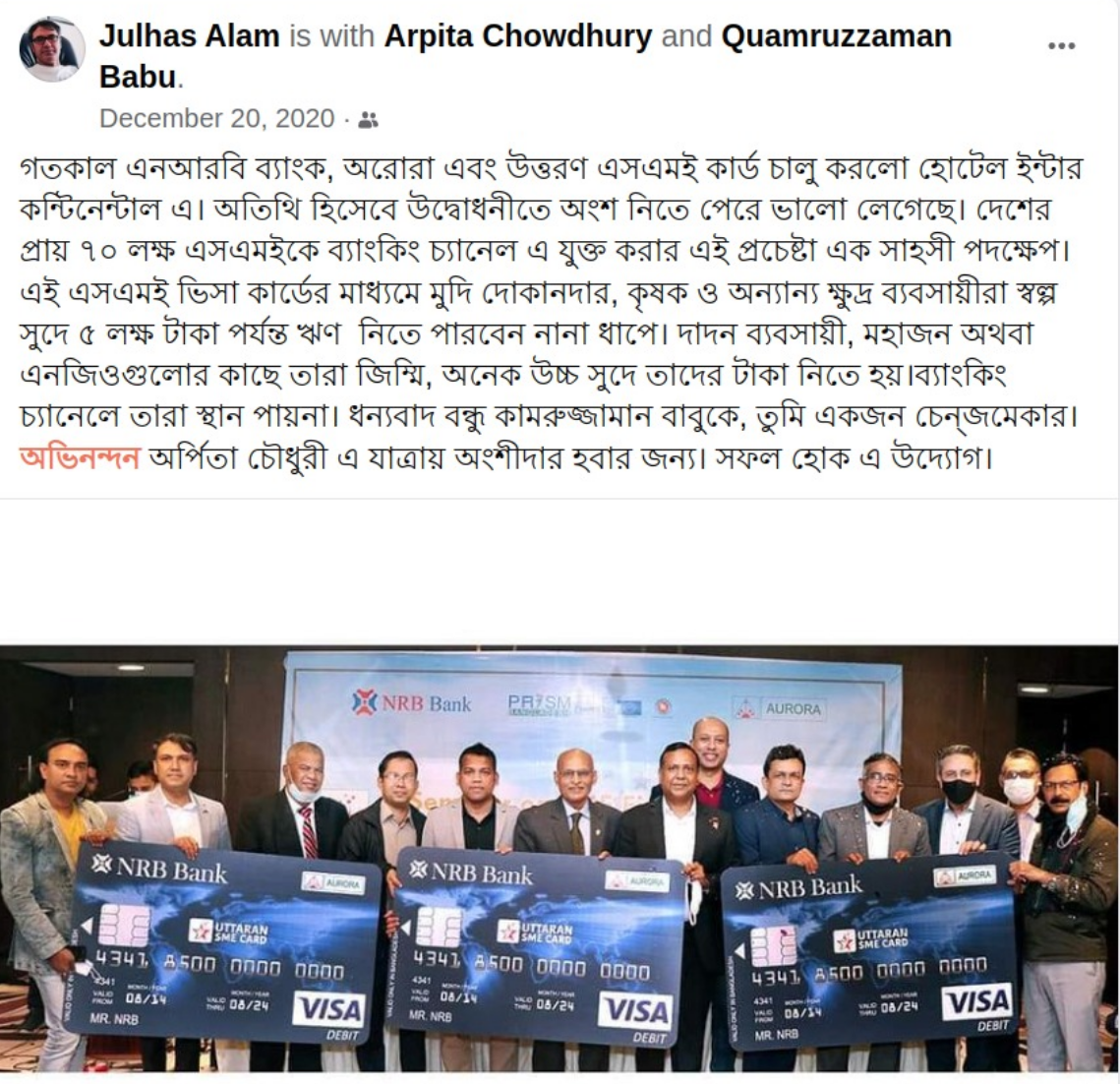

Around 2019, Julhas Alam engaged himself with an unregistered public relations firm, BizNext Plus, set up by his friend Arpita Chowdhury, according to three people familiar with the duo’s operations.

Sumel Sarker, who considers Alam a mentor and hails from his ancestral village in Mymensingh, handled a key portfolio at the PR firm. Sarkar acknowledged Julhas’ ties with the PR firm when a Dhaka-based journalist approached him.

“He is connected,” Sarkar said of Julhas’ role.

An editor of a news website in Dhaka, who declined to be identified because of his personal friendship with Alam, also corroborated his ties with BizNext Plus via an intermediary.

Alam appeared alongside Arpita Chowdhury in events hosted by multiple clients of BizNext Plus. Those events have little relevance, if at all, to his beat of coverage as an AP correspondent.

In September 2019, he was at a signing ceremony between BizNext Film and the producers of a low-profile Bengali feature film to handle its public relations.

The film’s director, Rashid Polash, wrote over Facebook Messenger: “Julhas was with BizNext Plus at that time, but I don’t know about the current status.”

A year later, Alam represented the AP to appear, alongside Chowdhury, at an event on SME financing by a private bank, also a client of BizNext Plus.

That was not his usual area of coverage as a foreign correspondent.

An email seen by Netra News confirms that BizNext Plus handled the public relations of a ruling party politician and businessman, Sheikh Fazle Fahim, the former head of Bangladesh’s apex trade body and the eldest son of the prime minister’s powerful cousin.

Alam wrote flattering Facebook posts about Fahim, travelled with his entourage to China, and quoted him twice in his AP stories.

AP’s statement on news values and principles prohibits its journalists from performing “public relations work for politicians or their groups.”

“When a [reporter] engages in events organized by a PR agency that frequently represents a political party or individuals in the political arena, it presents a clear conflict with the principles outlined by AP,” said Haq, also a former professor of journalism at Dhaka University, Alam’s alma mater, who agreed to assess Netra News’ findings per AP’s policies.

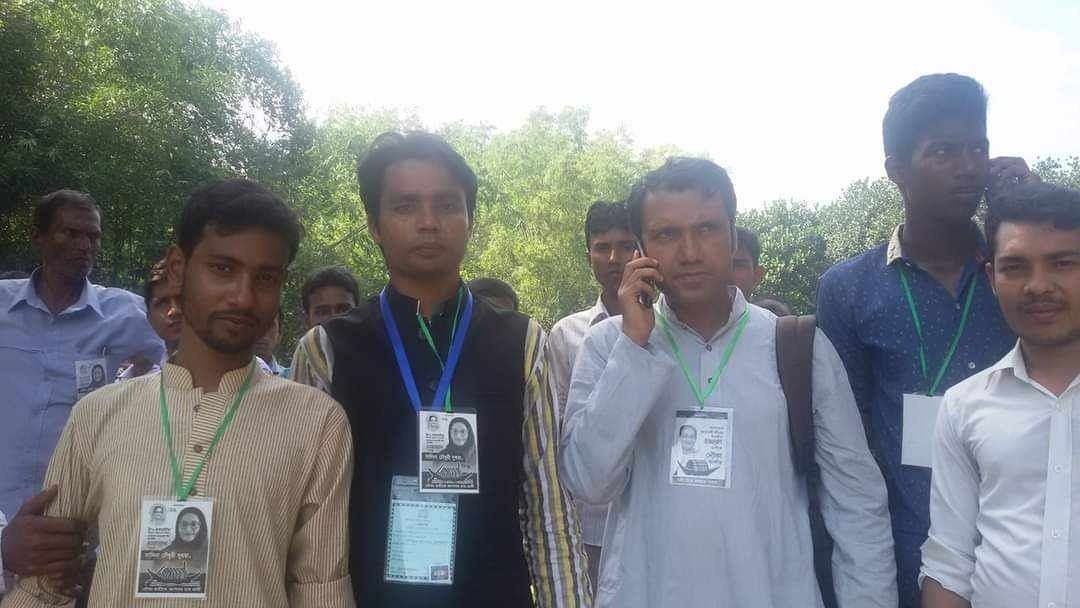

Alam has an even more direct relationship with the ruling Awami League party. His wife, Salina Chowdhury, ran for local council office on a ruling party ticket in Fulbaria, Mymensingh.

Social media posts suggest he participated in the campaign as her electoral agent, wearing a badge that bore the photo of the prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, and Awami League's electoral symbol, boat.

AP journalists are expected to avoid partaking in any political activity.

Coverage tainted with opinion

In public statements, Alam displayed an extraordinary appetite for accepting unproven allegations by the ruling party as evidentiary truth.

In a recent talk show hosted by an extremely pro-government coalition of the media, he participated as a panellist and raised a serious allegation that the US Ambassador in Dhaka, Peter Haas, was “blackmailing” the Bangladesh government, without offering any evidence.

He also accused Haas of “violating” diplomatic norms by raising “unnecessary” security concerns.

In December last year, Peter Haas visited the house of an opposition activist whose family alleges he had been disappeared by state agents. But the US envoy was forced to cut short the visit due to security concerns as protesters reportedly tied with the ruling party appeared outside the house unannounced.

In 2018, the convoy of the then-US ambassador, Marcia Bernicat, suffered a violent attack led by ruling party activists, but she escaped the attack unharmed. Only recently did the government charge nine individuals, including several ruling party activists, in relation to the attack.

In May this year, the Bangladesh government withdrew the police escort in charge of the ambassador’s security.

In 2019, referring to The World Bank’s withdrawal of funding from a major infrastructure project in Bangladesh, citing an alleged corruption scheme, Alam said at a chat show, “You know, the World Bank made an allegation of corruption. Our honourable prime minister took that very seriously. She went ahead with the project very courageously, defying all the conspiracies.”

The “conspiracies” that he was referring to echoed similar unproven charges made by the ruling Awami League and Hasina about Hillary Clinton, the former US secretary of state, and Muhammad Yunus, Bangladesh’s only Nobel winner known for his work on poverty alleviation.

Hasina repeatedly alleged that Clinton and Yunus had orchestrated a scheme to force The World Bank to withdraw its funding for the infrastructure project in an attempt to embarrass her. The government has never offered any proof to back up the claims, and Yunus and the World Bank repeatedly issued strong denials.

In addition to displaying a tendency to be overly receptive to the government narrative, that is also a violation of AP guidelines, which ask its journalists to refrain from “declaring their views on contentious public issues in any public forum.”

Contrary to his generally uncritical coverage of the government, Alam seldom highlighted serious abuses facing the opposition, such as violence caused by security forces or systematic abuse of the judicial process to harass opposition activists.

On December 4th 2022, during a TV show, Alam suggested that the opposition may have staged the violence its activists faced. “A single death of an activist often changed the tide of protests in respective political parties’ favour,” he said. “In Bangladesh’s context, these acts of violence are often staged; it’s a mechanism (strategy) for political parties.”

He also echoed a ruling party talking point about the opposition making profits by awarding nominations to its candidates. “In BNP, they have a crisis,” he said. “In the last election, there were allegations of profiteering from awarding nominations.”

The ruling party often invokes the unproven claim to assert that the BNP lost by unfathomably big numbers in the 2018 election — in which the ruling party won 96% of the seats — because of its internal rivalry, as opposed to widespread government rigging, as alleged by independent observers.

No BNP candidate has ever claimed the party had asked for money in exchange for nominating them as a candidate, nor has the ruling party provided any evidence. Alam also admitted that there was no evidence to support that claim, but he said he had “reasons” to believe the claim was true.

In another discussion with a different TV station, he termed “objectionable” a statement by six European parliament members calling for a free and fair election under a non-partisan government in Bangladesh.

In 2011, after a controversial court ruling, the government unilaterally abolished the non-partisan caretaker government system from the constitution despite strong protests by opposition parties.

The caretaker governments had organised four relatively credible elections, including the one in 2009 that the Awami League had won to return to power. The two elections held under the partisan government ever since have never gained credibility from international and independent observers.

In fact, at the heart of the current political crisis in Bangladesh is the dispute about the electoral system: the opposition parties demand a return of the caretaker or impartial non-partisan interim government to oversee the national elections, while the ruling party vehemently rejects the idea.

And Alam appeared to have taken a side in such a contentious political debate — one that he covered as a journalist — violating AP rules prohibiting its reporters from doing so.

Reporting in defence of the government

A review of Julhas Alam’s reporting for the AP also suggests a tendency to present a defence of the government.

When a top UN human rights official visited Bangladesh last year, the biggest story in the country was a documentary produced by Netra News, titled “Aynaghar” or the House of Mirror, in which it uncovered the existence of a secret prison where the country’s military intelligence had illegally detained political prisoners.

The UN official reportedly addressed the documentary’s allegations in her meetings with government officials and rights activists. She also met family members of victims of enforced disappearance during the trip. But Alam, in his dispatch for AP, omitted the entire framing, focusing only on the official’s comments about the Rohingya refugees, for which international actors generally praise the Dhaka government for its “generosity.”

When the New York-based Human Rights Watch published its detailed investigation into the confirmed enforced disappearance of 86 people, some linked with the political opposition, a dispatch from Dhaka, albeit not bearing Alam’s name, chose to frame the story from the perspective of the government.

“Bangladesh disputes study into alleged enforced disappearances,” the story was titled.

It also gave a disproportionate amount of credence to government sources, who seized on the opportunity to discredit the report as based on anonymous sources.

HRW does not appear to be given a chance to defend itself.

That appears to be the only instance in which a Bangladesh-related story filed from Dhaka and without any input from foreign colleagues that mentioned the term “enforced disappearance.”

Alam went to such a length to avoid discussing gross rights abuses that he never mentioned the 2021 US sanctions against Bangladesh security forces in his AP dispatches. But in his role as a commentator for local TV chat shows, he provides clues as to why.

In a recent talk show, he suggested Sheikh Hasina was right to criticise the US for imposing sanctions against an elite police unit for gross rights abuses.

“I think the government has handled the situation rightly,” he said, referring to Hasina’s blistering response to the US announcement.

As in Alam’s public commentaries, Hasina always gets a fawning treatment in his AP stories.

In election coverage in 2018, he called Sheikh Hasina an “iron lady”, which is a pejorative by Western standards reserved for authoritarian leaders, but he twisted the term as a badge of honour. “She’s developed a strong persona as an iron lady after her fierce response to a 2016 attack by radical Islamists on a cafe in Dhaka’s diplomatic quarter,” he wrote.

In another story, he wrote about how Hasina was courting votes by promising development. Alam concluded the story with Hasina’s quote urging people “to be brave” and go to polls as if the opposition was obstructing people from exercising votes.

In reality, the Awami League ended up “winning” more than 95% of the seats in an election that The Washington Post compared to North Korean and Syrian ones: Many of the polling stations saw close to 100% voter turnout, the likely result of intense vote rigging.

For his post-election report, instead of focusing on credible allegations of election manipulation, Alam was quick to write about an outpouring of support from the international community for the Sheikh Hasina government. “Congratulatory messages are flowing to Bangladesh Prime Minister-elect Sheikh Hasina,” he wrote, describing how leaders from Saudi Arabia to Bhutan were lauding her on winning the third straight term in power.

That was aligned with the ruling party talking points at the time — that these congratulatory messages showed the newly elected government was perfectly accepted by the international community, negating Western reservations about the credibility of the election.

In this story, too, Alam let Sheikh Hasina have the final say.

“She dismissed questions about the fairness of the vote and said it was a “very peaceful election”,” he wrote. ●

UPDATE: The story was updated to fix styling and editing errors and attach an additional photo – of a business card – following the 24th paragraph.